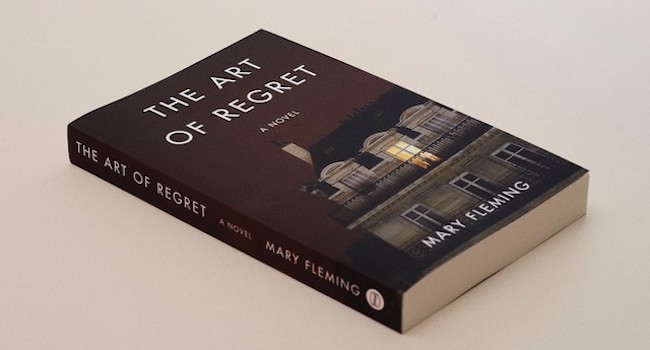

Book Review: The Art of Regret, A Novel by Mary Fleming

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Trevor McFarquhar is the protagonist, and narrator, of The Art of Regret, a novel set in Paris, to which he was brought–quite unwillingly–by his American mother, into a life in France at the age of eight. Now in his late 30s, it is a trauma from which he has not yet healed.

This passage, in which he and a British woman are getting to know each other, reveals his profound cultural disorientation.

“Well,” she said…”All I’m trying to say is that I’m one of those people who feels more at home away from home. But what about you? Where do you feel at home? Where is your home? It’s hard for me to imagine having two bona fide cultures. “

I shrugged. “I don’t know. Here, I guess. It’s where I live.”

…She nodded, thinking. “But do you feel French?”

“In some ways, yes. In others, not.”

“Do you feel American?”

“I tried very hard to, for most of my childhood. But when I went there to college for a year, I felt like a total freak. “ I paused. “I don’t feel one thing or another because I don’t really feel comfortable anywhere.”

Taken by Anemone123. Image © Pixabay

Because of his bicultural upbringing, however, Trevor is able to see both sides of things in a way that many French people—as well as expatriates in France—are unable to. In this passage, he describes a conversation between a group of American churchgoers at a dinner party attended by a mixed group of French and expat guests.

“Well, it’s not for any shortage of restrictions,” [said] Leslie. “Our children are having real trouble adjusting to that at school—and the school is supposed to be bilingual. We incorrectly assumed that also meant bicultural.”

That was it. They were launched like a rocket into the wide-open space of French Bashing. Leslie and Don, having been in France for only a year, led the attack, at moments with a viciousness I found most un-Christian. Diane, married to a Frenchman and, minus long summer vacations in Vermont probably stuck here for life, veered from commiseration to explanation to mediation. She was keenly involved in several volunteer associations promoting better understanding between the two countries. No wonder she found the inability to reach an agreement with her French husband on the utility or futility of bicycle helmets so troubling.

Taken by Corey Agopian. Image © Unsplash

The story unfolds between the years of 1995, at the time of a massive transit strike that crippled the country, and 2000. During the strike, Trevor’s situation gets both better and worse: the bicycle shop he inherited, which he has been completely disinterested in and very bad at managing, takes off; but, as a result of a phenomenally bad decision on his part, he manages to turn his family relations from a kind of chilly entente cordiale to nearly complete alienation.

Without giving away the plot, I’ll just say that that is not, however, the end of the story.

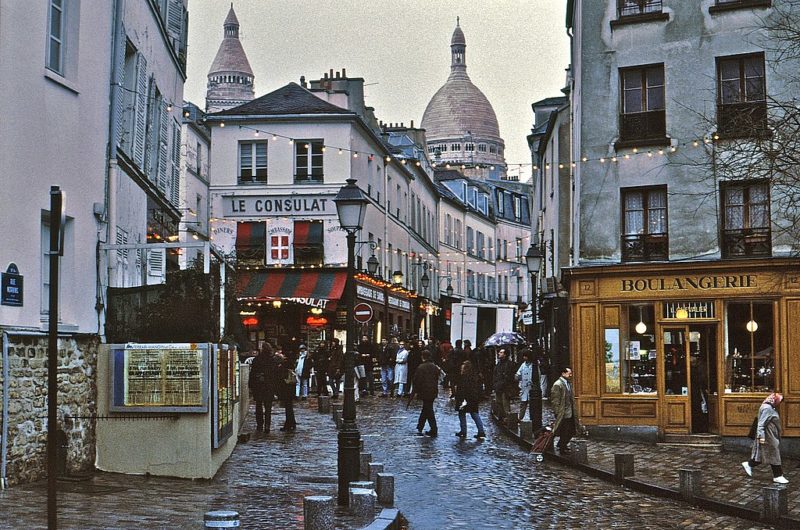

The detailed descriptions of Paris will be especially appreciated by those who know and love it. Here is one example of the visually precise, evocative prose that characterizes Fleming’s writing.

All these years later the beauty of the city was again proving salutary, therapeutic. The color of the stone or the uneven symphony of buildings jutting up around Montmartre; the sun reflecting in an incendiary orange off the wrought-iron balustrades or a glimpse at a bold cloud, its fifteen shades of gray exploding above a line of zinc roofs.

Montmartre 1993. Image © Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

Aside from the aspects that are specific to living abroad, this story is a universal one: it is a story about the inevitable difficulties of family life; the emotional wounds left by loss; and the painful secrets that lie at the heart of most families. Trevor has never really accepted his mother’s decision to take him and his brother to France after the death of their father and sister. He resents her for having done so, and his younger brother for having adapted so well and so thoroughly to the move. And he has never accepted his French stepfather. These facts, along with others–and most of all because of the way he decides to deal with them–have turned him into a rather sour character. An attractive man who has no trouble finding lover after lover, but is unable to find, or to give, love. A talented photographer who gives up on his passion for photography and falls somewhat grumpily instead into a not-at-all successful career as the owner of a bicycle shop.

But although he is certainly not an exemplary figure, despite his many faults he is, somehow, a likeable one anyway. Trevor McFarquhar is an “Everyman,” an ordinary person with whom anyone should be able to readily identify. For what decent person, no matter how good a life they’ve led, can fail to have pockets of regret about things done, or not done? And who among us doesn’t feel twinges of regret when we think about all the ways we could have done better, been better people?

Regret. Taken by Lucas clarysse. Image © Unsplash

There are many other wonderful, well-developed characters as well, including Trevor’s invaluable Polish shop assistant Piotr, and his wife; and a variety of neighborhood figures, from waiters and bartenders in the cafés Trevor frequents, to the clochards who hang out outside of them waiting for handouts.

It is Trevor’s ability to feel regret, I think, and his longing for something that he can’t really figure out how to achieve, that makes him a sympathetic character despite his self-centeredness, and his generally negative disposition. “Photography is the art of regret,” he says at one point,

And since in my life generally I had cultivated regret to the state of an art, it was no wonder I felt at home in a form of expression that yes, preserves memory, but also causes constant, aching reminders of all that is missed.

Author Mary Fleming

We want–at least this reader wanted—very much, for him to find a way to “snap out of it.” To grow up and move on, finally, with his life; and to make something of it.

Is he able to do so? Well. If you want to know the answer to that question, you will just have to buy the book.

Purchase this book at your local independent bookstore (in Paris, we recommend The Red Wheelbarrow, San Francisco Books, Shakespeare and Company), or on Amazon below:

Lead photo credit : The Art of Regret novel cover. Image by Mary Fleming

REPLY