Belleville: Paris of the People

At the crossroads of the 10th, 11th, 19th, and 20th districts, Belleville is known among Parisians as a miniature Chinatown and for its rowdy bars. But who knew that the area’s history was so rich in entertainment, and that the seeds of uprisings were sown right here in eastern Paris? Even before it was a part of Paris, Belleville was already the city’s most talked-about party district, beginning with the construction of a wall in 1785.

Faced with debt before the French Revolution, Louis XVI decided to build a tax wall around Paris. Whereas most walls built throughout the centuries in Paris were fortification walls, this one was designed to relieve the state’s financial woes.

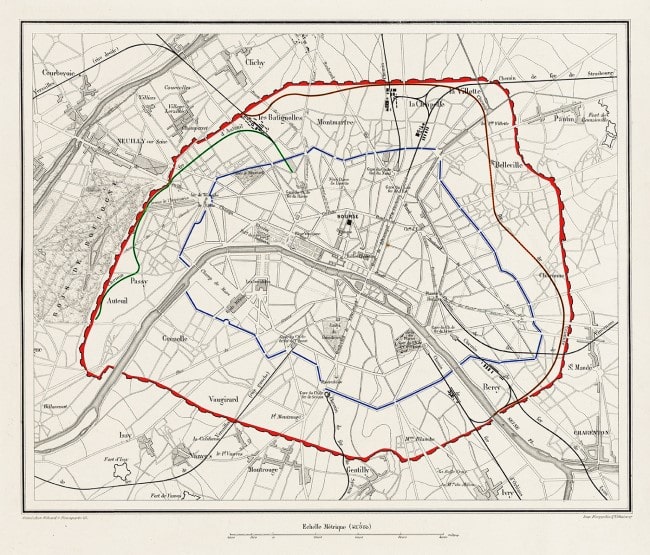

The Farmer’s General wall, as it was known, was 24 kilometers (15 miles) long. The wall surrounded Paris from 1785 to 1860, and those old city limits are still visible today: they follow metro lines 2 and 6. Belleville, its own bustling city, independent from Paris until 1860, sat right outside the new wall.

Goods such as construction materials and heating fuel were taxed as they entered Paris. Also among those taxed goods were food and drink. After the Farmer’s General wall was built, it was much cheaper to drink and eat on the outside of the tax wall.

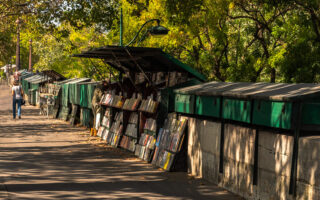

This was especially true in Belleville, where fruit orchards and vineyards covered the area’s hills. Cheap wine (piquette) was produced directly on site, and so in Belleville all sorts of leisure establishments grew up almost overnight. Cabarets, theaters, and goguettes (singing clubs) provided inexpensive entertainment for the working class.

But in 1785, the French Revolution wasn’t far off, and some historians consider the Farmer’s General wall as one of the direct causes of the Revolution. People at the time said Le mur, murant Paris, rend Paris murmurant or “The wall walling Paris is causing all of Paris to murmur.” But Parisians were doing much more than just murmuring – they were getting angry.

Eat, drink, and be merry

But in Belleville, people gathered, ate, drank, and danced, often in those goguettes or singing clubs that literally pressed up against the Farmer’s General wall. From drinking songs to patriotic hymns, every type of singing performance was welcome in these clubs; one group’s name was the “Infants of Bacchus”! The police stayed close, because they rightly suspected that the creative freedom available in these establishments might be fomenting revolution: political free-thinkers and anarchists gathered right here in Belleville.

Still, the fun continued: nearby, a fair stretched out along the boulevard, where people watched animal tamers and flame throwers, listened to singers with accordions (known as “suspender pianos”) and bet on street fighters. They ate waffles and apple turnovers, and theater actors’ flamboyant costumes enchanted the crowds. In 1812, Belleville also had fireworks displays, an artificial lake, and theme parks, including one of the very first “roller coasters” in France!

Les Montagnes Russes a Belleville (C) TaylorHerring, Flickr

The first “roller coaster” in Belleville

Belleville even had its own Mardi Gras festivities from 1830 to 1839. Complete with disguises, drinking, and dancing ‘til dawn, revelers restored themselves by stopping in for a bowl of bouillon at Dénoyez Tavern, where they met wedding parties who were also supping (from the French word souper). Even to this day, at traditional French weddings, those who are still awake and going strong at 4 a.m. are served a steaming bowl of onion soup!

Entertainers and their audiences had plenty of room for carousing in the numerous establishments in Belleville: after the tax wall was built, the number of bars and cafés in Belleville grew at an exponential rate, reaching an astounding 448 by 1910. But local workers also frequented the area, including women: sometimes they attended cafés with their husbands on Sundays. More often though, women went with their colleagues in a group, and drank a zézette, a mix of absinthe and white wine, and their patronne, or boss, paid for it.

The Absinthe Drinker, Edgar Degas (1876), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Photo: Wikiart, public domain

Agitation

By the late 1800s, alcoholism was rampant. Absenteeism from work on Mondays was high: after spending Sunday with their families, men would make the rounds in the various taverns of Belleville. It was called “celebrating Saint Monday” (fêter la Saint-Lundi). One cause of alcoholism might have been the tiny, unsanitary apartments where workers lived: 12 m2 (144 square foot) dwellings for whole families pushed people outdoors and into taverns.

But other factors contributed to the agitation: even though the tax wall came down when Belleville was incorporated into Paris in 1860, revolution was still afoot. Uprisings in Paris in 1832 – about which Victor Hugo wrote in his 1862 work Les Misérables – and in 1848 had already mobilized Parisians twice before.

Additionally, Baron Haussmann’s modernization of central Paris in 1852 drove out the nearly half-million working-class Parisians, and many of them settled in eastern Paris. In 1870 Napoleon III lost the Franco-Prussian war, for which many eastern Parisians had been recruited. After the Second Empire was overturned in the fall, a famine struck, adding fuel to the working-class fire.

By the late 1800s, one out of every ten anarchists in Paris lived in Belleville. They gathered in taverns to sing and help organize the last uprising in Paris, La Commune, which was a direct result of the loss of the Franco-Prussian war. In 1871, President Adolphe Thiers ordered the disarming of Paris and his attempt to take back 227 cannons located in Belleville and Montmartre ended in barricades around the city, erected by angry Parisian.

All over Paris, Communards destroyed symbols of the state: public buildings were set on fire, and the column in the Place Vendôme was toppled. By the end of May, fighting was concentrated in Belleville, and the highest barricade, and the last to be destroyed, was located on the corner of the rues Ramponeau and Tourtille.

Barricade in Paris (C) Unknown, Public Domain

The last barricade

The revolutionaries in Belleville would never come any closer to their dream of self-government than in 1871. But their rebellious spirit and love of entertainment still live on in the streets, cafés, and bars around Belleville. Today, graffiti artists, poets, and incessant conversationalists still gather in bars like Aux Folies, where you can find cheap wine, and if you’re lucky, the occasional accordion player.

Historical sources

Belleville cafés by Anne Steiner and Sylvaine Conord

The Farmer’s General wall

Photo credits

Lead photo credit : Route of the Wall of the General Farmers (in blue) and of the enclosure of Thiers (in red) © ThePromenader via Wikimedia Commons

More in Belleville, French history, history

REPLY