Flâneries in Paris: Surprises at Sèvres-Babylone

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the eighth in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

Sometimes, I plan a walk to see specific things. Sometimes, I just set out to see what turns up, and in this case, walking no further than 15 minutes from the Sèvres-Babylone metro station, I found a number of surprises: a little corner of Indo-China with connections to Louis XIV, a church I’d never heard of which nearly 2 million people visit every year and a set of giant pink flying creatures which appeared to have been blown from bubble gum. To name but three…

Hôtel Lutetia. Photo credit: Celette / Wikimedia commons

I did already know about the first thing I spotted: the Hotel Lutetia on Boulevard Raspail, just by the metro exit, played a central role in the German occupation of Paris in the 1940s, when it was requisitioned by the Nazis. In 1945 however, on the orders of General de Gaulle himself, it became a center for displaced persons arriving in Paris, many of them from the concentration camps. The plaque on the wall recalls both the joy of those who came here having found their freedom and the anguish of those who waited in vain for relatives who never arrived. Today the Lutetia, which reopened in 2018 after a massive four-year restoration, is the only designated “palace” hotel on the Left Bank.

Square Boucicaut @ corno.fulgur75 at Creative Commons

What else could I find? I crossed through Square Boucicaut, one of those tranquil little Parisian parks which manage to be both well-ordered and well-used. The mature trees and little pathway named after Pierre Herbart – author and resistance fighter – who died in 1974, resonated continuity, but the office workers enjoying some lunchtime sunshine and the moms with baby slings and trailing toddlers heading for the playground spoke very much of today. A notice reminding everyone that “the grass takes its winter rest between mid-October and mid-April” seemed reassuring, a promise that all would always be well in this pretty little corner of Paris.

La Chapelle de l’Épiphanie @ Thomon at Wikimedia Commons

Around the corner on Rue du Bac I came across the Chapelle de l’Épiphanie and as it seemed to be open, I ventured inside. It is, explained the information panel, the HQ of the Paris Foreign Missions Society and dates back to the 17th century, when Louis XIV supported it and so a stone bearing his image lies in the foundations. But this is not just a historical site, it is very much a functioning institution which oversees the training of new missionaries preparing to serve in Asia. Who knew? I certainly didn’t.

Chapelle de l’Épiphanie @ Marian Jones

Across the courtyard stood the chapel itself, and just inside it was a large memorial recalling the Catholics from Indo-China who died for France during the First World War. Some 45 names were listed, along with the countries from which they came: Cambodge, Annam, Laos… Information boards detailed many examples of missionary work, past and present, and Charles de Coubertin’s Painting of Missionaries’ Departure depicted the touching scene in 1868 when newly-trained missionaries, just about to go abroad, lined up at the altar, and every member of the congregation filed past to kiss their feet. There are other historical resonances; the funeral for the writer Chateaubriand was held here in 1848, attended by both Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac and around the same time the chapel organist was one Charles Gounod, composer of a dozen well-known operas. But it remains very much an institution for today, with some 180 priests who trained here currently serving in southeast Asian countries.

Five minutes away, according to my map, was the marvelously named Chapelle Notre-Dame de la Médaille Miraculeuse, of which I’d never heard, although I later learned that it receives nearly 2 million visitors a year. The little entrance on Rue du Bac opened up to reveal a walkway, quite bustling with people heading for the church at the far end. And it turned out to be a beauty: cool cream walls, lots of plain wooden pews and a stunning archway built around the altar, painted in blues and silver with words of Christian welcome curving around it in gold. It seemed that lots of people knew about this little haven. I wondered why.

Chapelle Notre-Dame de la Médaille Miraculeuse @ Lawrence OP at Creative Commons

The answer came in the stone panels which lined the walkway, telling the story in words and pictures of Catherine Labouré, one of the young nuns from the order called Filles de la Charité, whose convent this was. She often prayed to the Virgin Mary here and one day in 1830, when she was about 20, Catherine had a vision in which Mary asked her to have a medal struck to commemorate their meeting. This was duly done and two years later, when plague struck in Paris and led to some 20,000 deaths, a bishop decreed that the medals should be widely distributed. When this coincided with a decrease in the number of plague cases, the medal was declared “miraculeuse.”

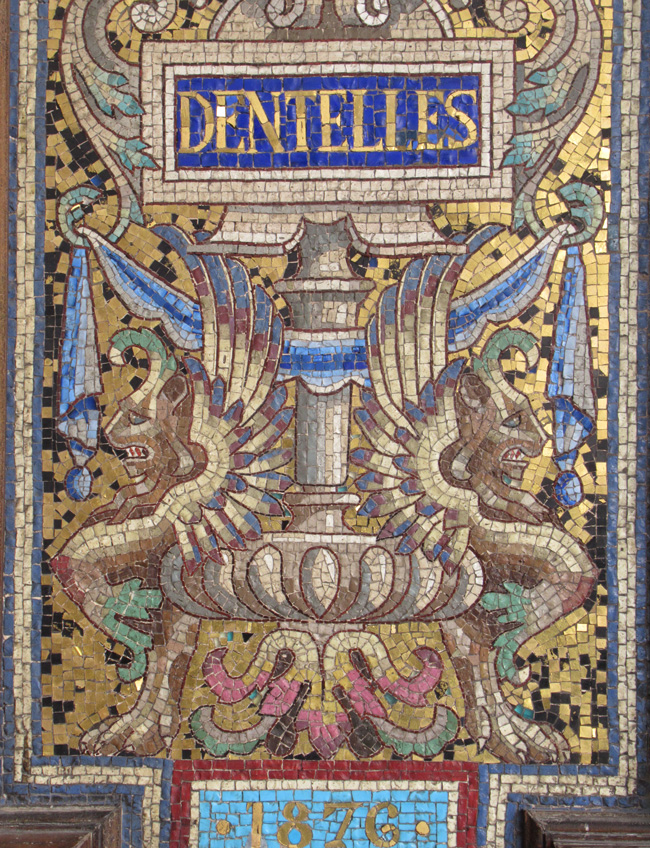

By 1834, some 500,000 had been struck and by the year of Catherine’s death in 1876, more than 20 times that many. Catherine was made a saint in 1947, and today the médaille miraculeuse is worn by millions of Catholics worldwide. It’s oval in shape, bronze in color, and has a picture of Mary on one side, together with the date, 1830. On the reverse is a cross intertwined with the letters M for Marie and V for Vierge (virgin) and around the edge, the words of a prayer asking Mary to intercede on the wearer’s behalf. So that’s why this site attracts so many visitors: Catholics all over the world know all about it and many come to see for themselves.

Jardin Cathérine Labouré @ Marian Jones

The Jardin Cathérine Labouré, on nearby Rue Babylone is another idyllic little spot, originally the kitchen garden of the convent. Quite large, it’s definitely worth exploring. I went past the adventure playground near the entrance and wandered the various pathways past lawns, flower beds, a little vineyard and some vegetable gardens. It’s peaceful and there are benches if you wish to sit and contemplate the lovely back view of the convent and the grounds which have been a place of work and prayer since it was first founded in 1633.

More secularly, on my way back to Sèvres-Babylone metro station, I passed the area’s best-known institution, the Bon Marché department store. I took photos of the Art Deco panels on the outside and popped my head inside for just long enough to admire the grand central staircase, hung this year with enormous pink characters, seemingly a cross between a giant baby’s toy and a visitor from outer space, blown perhaps out of bubble gum. The store commissions an artist every year for a new piece of work and this year Philippe Katerine has filled the atrium with these huge pink blubbery creatures, his take on “mignonisme,” or “cutism.”

I decided to leave shopping for another day and for now to head next door to the equally famous Grande Épicerie where I knew I would find all kinds of edible treats – Lindt chocolate tasting of “figue intense,” Armagnac-flavored pâté – and tempting souvenirs such as giant cheerfully decorated tins of Mère Poulard’s biscuits and the perfect beverage for history lovers, Thé Marie Antoinette. Better still, their café offered a whole selection of little temptations to indulge in after my walk. I opted for limonade artisanale and a Paris-Brest. Perfect!

Enjoying our “Flâneries in Paris” series? Read Marian’s previous article, exploring the Sorbonne and Latin Quarter, where students have gathered for more than 800 years, here.

Lead photo credit : Sèvres Babylone, Paris @ Phil McIver at Creative Commons

More in Catherine Labouré, Chapelle de l’Épiphanie, Flâneries in Paris, Rue Babylone, Rue du Bac, Sèvres-Babylone