Flâneries in Paris: Explore the Sorbonne and Latin Quarter

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the seventh in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

It’s never too late to dream of being a student in Paris! And where better to start a meander through the streets where students have gathered for more than 800 years than at Cluny-la-Sorbonne metro station? A glance at the ceiling, decorated with the signatures of writers and intellectuals connected to the area is a reminder of its central role in the city’s intellectual life: Rabelais, Sartre, Molière, Baudelaire…..

Along the Boulevard St Michel, I passed the newly reopened Musée de Cluny, where the medieval treasures are a reminder of the days when university learning in Paris first began. Then came the Librairie Gibert Joseph bookshop, filled to bursting with new and second-hand books, some of them spilling out into racks on the pavement, followed by a left turn into Rue des Écoles, with more bookshops and brasseries. I soon came to the Sorbonne itself and, opposite it, the bronze statue of the Renaissance philosopher Montaigne, gazing benignly into the middle distance, as if lost in thought. His shiny right foot is a testament to a long-time student tradition that students pass by to rub it the night before an exam, hoping it will bring them luck. Sometimes they greet him with a cheery “Salut, Montaigne!”

Librairie Gibert Joseph bookshop @ Marian Jones

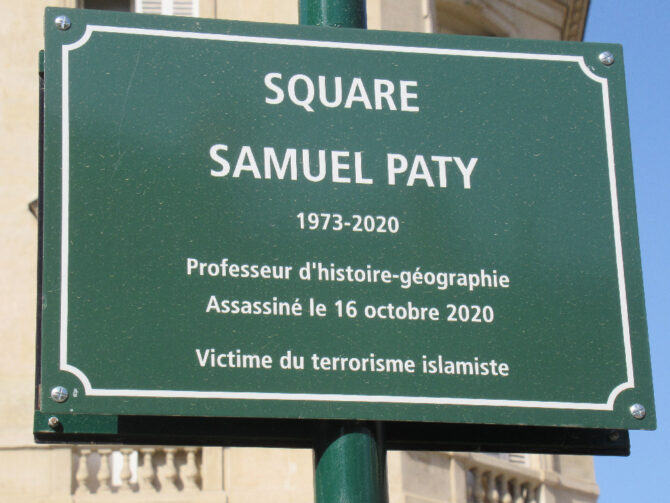

The statue is outside a pretty little park, the Square Samuel Paty, newly renamed in memory of a tragedy in October 2020 in a Paris school. History-geography teacher Samuel Paty was brutally murdered in an act which President Macron later called “terrorisme islamiste.” Monsieur Paty had incited fury in some quarters for discussing the Charlie Hebdo cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed in class. Siting a memorial here, explaining that “Il défendait les valeurs de la République,” reinforces the message that in the strictly secular French school system, freedom of speech should be respected.

The Sorbonne sits on the corner of the Rue St Jacques, and its façade stretches down its right-hand side for half a kilometer with the names of the disciplines taught carved into arched panels along the top of the building: géographie, paléontologie, algèbre and dozens more. On the side of the road are other illustrious educational institutions such as the Collège de France, founded in the 16th century and still offering free public lectures today. Behind it is the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, one of France’s most prestigious schools, named after Louis XIV and alma mater of such luminaries as Molière, Delacroix, Jacques Chirac and André Citroën, founder of the motor company.

Here too I spotted an information panel which reminded me that student life is not all about intellectual pursuits. In the 15th century, the poet François Montcorbier was adopted as a six year-old by a chaplain of the St Benoît de Bétourné church (no longer here) and he was encouraged to study and better himself. Unfortunately, laments the text, he was “more drawn to taverns and girls than to scholastic life” and he is known to have been prosecuted for a number of crimes. It’s a little picture of the drinking culture and bawdy behavior which went along with university study. T’was, I thought, perhaps ever thus!

I made my way to the Place de la Sorbonne, passing a shabby poster on a nearby wall which gave an insight into the student politics of today, calling students who are “anticapitalistes et révolutionnaires” to action. The square itself is a pretty little haven, with benches clustered around a central fountain and the surrounding cafes have names like Tabac de la Sorbonne and Café l’Escritoire. It is just the place to chat over ideas between lectures, or perhaps to read a book from the square’s bookshop, the Librairie Philosophique J Vrin, where titles on display in the window include Marx’s Class Struggles in France and the enigmatic Is there any Hope for Hope?

I retraced my steps along the Rue Cujas, which also has a very university feel. Here you can spot the Faculty of Law, pop into a copying shop, or stop off for galettes-crêpes and bubble tea. I then crossed the Rue St Jacques towards the Place du Panthéon and walked the length of the gorgeous Bibliothèque St-Geneviève, the university library built in the 1830s on the site of a much older seat of learning where Erasmus of Rotterdam studied for a year in the 15th century. All along its façade, panels are engraved with dozens of names, illustrating the breadth of reading to be found inside: Pliny the Younger, Machiavelli and Balzac, to name just three of the hundreds listed.

Bibliothèque St-Geneviève. Credit: Priscille Leroy/ Wikimedia commons

Opposite the library were today’s students, clustered on the stone benches and tables provided – along with litter bins! – as a venue for lunch or a chat. I had read that this was a gathering place for students in the Middle Ages, somewhere to meet and to listen to outdoor lectures on theology given by churchmen. It was this which gave Robert de Sorbon the idea, in 1257, of providing board and lodging for young men who wished to stay here and pursue their studies. The 20 or so students he began with became some 20,000 by the end of the Middle Ages and by then the university named after him – the Sorbonne – was fast gaining a reputation throughout Europe. I wondered if the students I saw enjoying their picnic lunch knew what a grand old tradition they were part of.

Students in the Sorbonne courtyard during the famous student protests of May 1968. Public domain

At the far end of the square stands the imposing St Étienne du Mont church, on a site where once there was a chapel serving the now disappeared St Geneviève Abbey. This little spot has been entwined with the history of Paris for over two millennia. The Romans were here and Clovis, known as the first king of France, who built a basilica on the site in the 6th century, is thought to be buried here somewhere. Inside this lovely church, begun by François I and completed by Louis XIII, I found some stunning sights. Large windows let in plenty of light and so the creamy stonework, arched into ribbed vaults in the ceiling and cut into a delicate, almost lacy pattern on the rood screen, is shown at its best. And here too was something I have always wanted to see: the resting place of the relics of Saint Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris. And the gilded copper shrine, nestling in a quiet corner of the church, was indeed a place to linger for a moment of reflection.

Église Saint-Étienne-de Mont. Photo: Diliff/ Wikimedia Commons

Rounding a corner past St Étienne (and the steps on which Owen Wilson sat in Midnight in Paris!) to make my way back towards the Cluny-la-Sorbonne metro station, I passed one more symbol of academic life in Paris. In the Place Jacqueline de Romilly, just behind the church, is a plaque explaining that Jacqueline, a respected classical scholar and novelist, was the first female member of the Collège de France and the second woman ever elected to the Académie Francaise. Currently, only about a quarter of the 40 “Immortels,” as members of the Académie are known, are women. It seemed fitting to end my tour of the student areas of Paris by reflecting that, for all the rich history of Parisian academia, there are still things which need to change.

Enjoying our “Flâneries in Paris” series? Read Marian’s previous article, Flâneries around La Madeleine, a prominent church with royal connections, here.

Lead photo credit : View of the Sorbonne and the district from the top of the Tour Saint Jacques. Credit: Jean-Christophe Windland / Wikimedia commons

More in Boulevard St Michel, Cluny-la-Sorbonne, Flânerie, Flâneries in Paris, Latin Quarter, Sorbonne