Flâneries in Paris: Explore the Cité Quarter

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the first in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

One sunny morning, with a couple of hours to spare, I got off the metro at Cité and went for a wander around the eastern half of the Île de la Cité, anticipating glimpses of history from the Romans to the 21st century and some of the loveliest views anywhere in Paris.

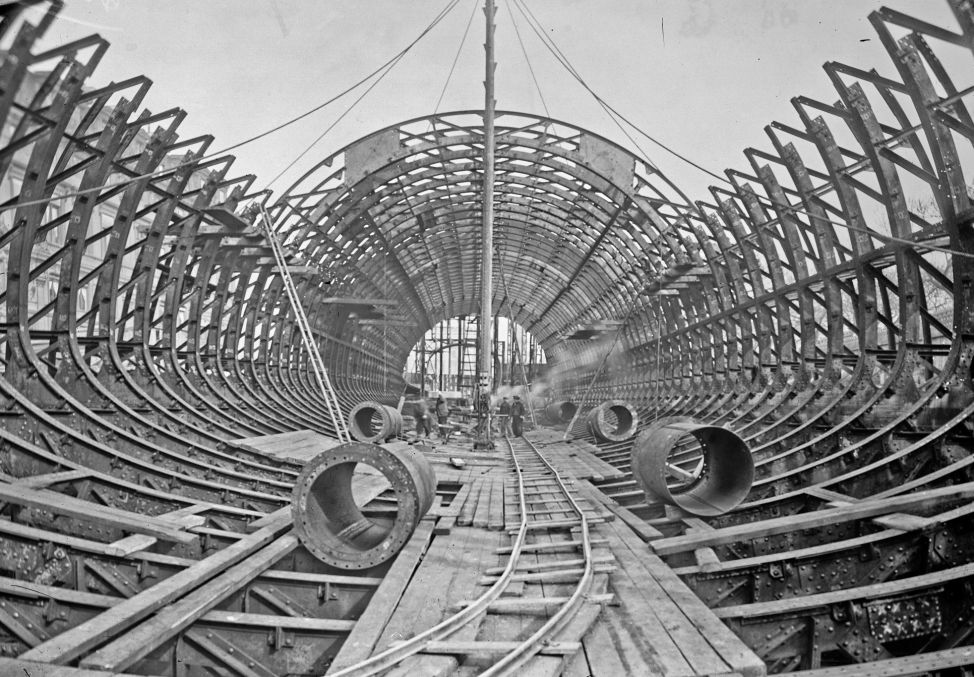

The Cité metro construction at Marché aux fleurs, 1907, Agence Rol. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Coming up the metro steps, I dived straight into the Marché aux Fleurs, to explore the little passageways crammed with plants and independent shops, such as Au Jardin d’Edgar, and La Maison de l’Orchide, offering greenery for “terraces, balconies and patios.” Flowers and shrubs spilled out abundantly, and I heard a shopkeeper advising on plants for a north-facing, fifth-floor balcony. Signs offering free delivery mean you wouldn’t have to battle over the metro with your delicate new plants. It’s not just for tourists; it’s also a garden center for the city of Paris.

The marché aux fleurs. © Marian Jones

Rue de la Cité led me down towards Notre-Dame, past a little plaque commemorating the day in February 886 when 14 Franks died defending a footbridge onto the island against invading Vikings. The names of these brave men resonate down the centuries, recalling how they threw hot pitch and wax against the catapults and battering rams of their enemy: Eudes, Comte de Paris, Gozlin Eveque, Ermenfroi… Victory wasn’t immediate; in fact Charles le Gros (Emperor Charles the Fat!) eventually paid the Vikings “700 pounds of silver” to sail away. But the sacrifice of these courageous early Parisians is not forgotten.

Count Odo defends Paris against the Norsemen, romantic painting by Jean-Victor Schnetz (1837), Galerie des Batailles, Versailles. Public domain

Next, I went towards the Parvis de Notre-Dame, the square in front of the cathedral, and popped down into the Crypte Archéologique to see parts left of the city known in Roman times as Lutetia. There I saw the remains of ancient streets, of the harbor the Romans built, and of the bathhouse where the citizens of Lutetia worked out how to pump in hot water so they could bathe, relax and socialize. The guide who welcomed me, however, was very 21st century. Yes, he said, he’s pleased to say tourists are slowly returning after Covid, “even” (as he put it) the Americans who are certainly “les bienvenus” (welcome) but whose ex -president he finds “catastrophique.” I never heard his opinion of President Trump’s successor because he had moved on to using his very colloquial English to tell the people behind me that the best solution, should they need a toilet, is to go to a café, buy a drink and “pee there.”

La crypte archéologique du Parvis de Notre-Dame. Credit: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra/ Wikimedia commons

Crossing the square in front of Notre-Dame, I passed the kilometre zéro plaque embedded into it, the spot from which the distance to Paris from places all over France is measured. Of course the cathedral is still shut, but lots of people had come anyway, eager to see how the repairs are progressing and to take photos. Skirting round to the left of the building, up la rue du Cloître-Notre-Dame, I had to weave between dozens of people who had stopped to read the information boards charting the restoration work done so far. Interest was keen: tourists and Parisians alike yearn to be able to visit Notre-Dame again. On my left, on the wall of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital, I saw a plaque commemorating another act of heroism and another key date. André Perrin, “gardien de la paix,” was shot here by the Nazis on the 19th of August 1944, the first day of the fierce last battle which ended a week later in the liberation of Paris.

Notre-Dame cathedral. Photo credit: Paris Info tourist office/ cmjn

At the end of the road I turned left onto the Pont de l’Archeveche, past the little Square Jean XXIII park which is currently closed because of the building works, but which will be a lovely spot to linger once it reopens. Across the road is somewhere I have long wondered about, but never visited and today was a chance to put that right. The Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation, inaugurated in 1962 by President Charles de Gaulle, is a memorial to the 200,000 French citizens who were deported from France to Nazi concentration camps during the Second World War. I walked through the garden, down the stone steps to the memorial entrance, right on the tip of the island. It was from here that so many were transported from Paris to their dreadful fate, families who had waited, as the inscription says, “dans la nuit et le brouillard” (in the dark and the fog), and were then taken away, mostly to the death camps.

Inside the memorial is a downstairs space, with quotations on the walls and a set of urns containing ashes from 15 different concentration camps, and to either side are stairs leading up to the information rooms. There are lists of camps, numbers of people taken from each French département, detailed descriptions of life in the camps and haunting photographs. In one family group is a little blonde girl, aged perhaps seven, and next to that photograph, an enlarged, illuminated copy of just her. There were so many numbers, of victims, of camps, of deaths, and that one photo spoke eloquently to illustrate them all. On my way out, back through the garden, I paused to look at the flower bed, planted with roses named Résurrection, created by women deported to the Ravensbrück camp and dedicated to “toutes les victimes de la déportation.”

It was strangely incongruous that as soon as I came out of the memorial I heard buskers on the Pont Saint Louis, and saw the Bargeaux Brothers treating passers-by to their super-chilled versions of “Bye-Bye Love” and “It had to be you.” A little crowd of relaxed onlookers had gathered, two of whom were jiving along in the sunshine. The river behind the duo – a cellist and a guitarist – sparkled, the Hôtel de Ville formed a splendid distant backdrop, and truly it was a moment to savor just being alive, and free to wander in Paris.

Buskers on the Pont St Louis. © Marian Jones

Continuing northwards into Quai aux Fleurs was a chance to head for some of the oldest parts of the island. The bouquinistes, little green cabins lining the riverside pavement, offered take-home reminders of old Paris: posters for Ricard’s aniseed drink, vintage copies of Vogue, paintings of Old Paris, one showing the Eiffel Tower tied up in a giant red bow. Kitsch? Yes, a little, but still somehow tempting! On the left-hand side were lots of houses with plaques, one recalling a lawyer-turned résistante who “lived here and loved this house for 70 years,” and another a 1950s French president, René Coty, whose name was not familiar to me.

The bouquinistes of Paris. Photo credit: Peter Olson

I knew about numbers 9-11 Quai aux Fleurs, though. It’s an elegant mansion, built in the 1840s, but the inscription above the front door explains that here once stood l’ancienne habitation d’Héloïse et d’Abelard. Yes! Formerly on this site was the house where the 12th-century university tutor Abelard fell in love with Héloïse, enraging her father to the point where he had Abelard attacked and castrated and sent his daughter to a nunnery. They exchanged passionate letters for the rest of their lives and were eventually buried together in the Père-Lachaise Cemetery. Looking up at the busts of them on either side of the inscription, I saw intriguing, faraway faces who spoke to me of heartbreak, but also of Paris as a city of romance.

Edmund Blair Leighton, Abélard et son élève Héloïse (1882). Public domain

Just past the house I turned left down some steps and into a maze of little streets leading back via the Rue d’Arcole, and past Notre-Dame to the Cité metro station. These winding streets just behind the Quai aux Fleurs had a medieval feel, in their narrowness, if not in the houses themselves and so it was easy to imagine Abelard slipping back to the house from Notre-Dame, where he sometimes worked, or from meeting his students, hoping to find Héloïse, alone in her father’s house, waiting for him.

I was soon back in our century, passing the souvenir shops of the Rue d’Arcole and the little café on a corner offering an intriguing choice of hot drinks in matching black cauldrons labelled in chalk vin chaud and chocolat chaud. But I took the memory of all those people from the long history of the island back with me onto the metro and away.

To find out more:

Archaeological Crypt (entry €9)

Memorial to the Martyrs of the Deportation (entry free)

The website to follow the progress on the renovation of Notre-Dame or to make a donation

Lead photo credit : The marché aux fleurs. © Marian Jones

More in Flâneries in Paris, history, Ile de la Cite, marche, walks in Paris

REPLY