A Voyage in Time: The Roman History of Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The City of Light that we all know and love was originally inhabited by the Parisii, an Iron Age Celtic tribe who occupied the area between the third century B.C. until the Roman conquest in 52 B.C. Settling on the Île de la Cité and the surrounding area along the banks of the Sequana River (the Seine), the Celts– whom the Romans called Gauls– named their settlement, Leucotecia, after the Celtic word, luco (marsh). The Parisii were not the first people to inhabit the banks of the Seine, but they they were the first to establish ongoing communities. They sowed seeds in the fertile soil, minted coins, built toll bridges, traded with others as far away as Germany and Spain, and enclosed their settlement with a wall — the first of eight walls built around Paris over the centuries.

Celtic tribes inhabited much of mainland Europe, comprising modern-day France, parts of Belgium, western Germany and northern Italy. The Parisii created what was thought to be an oppidum (fortified Celtic village) on the Île de la Cité, but no trace of this has been found. However, archaeological excavations between 1994-2005 in Nanterre (ancient Nemetodunum), have revealed streets and the ruins of houses over a 15-hectare area, as well as tombs, weapons, ornaments and pottery, suggesting that this was actually their oppidum.

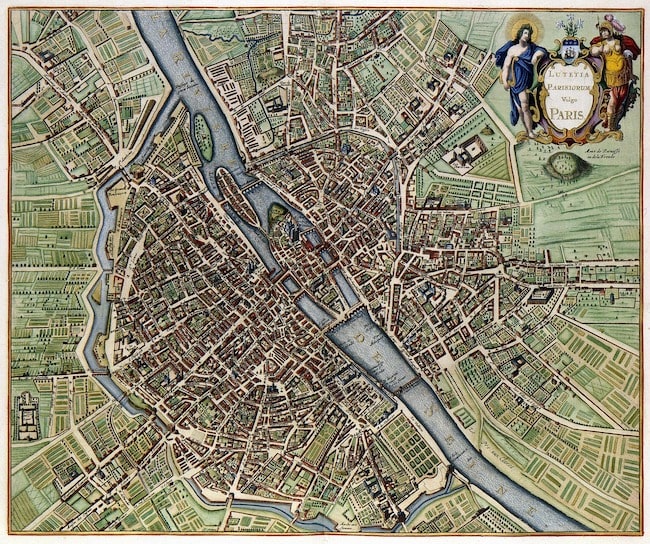

A map of Lutetia, Paris. Photo © WikiImages, Pixabay

During the 40-year reign of Julius Caesar, the Romans launched a military campaign against the Celts, killing them by the thousands and destroying their culture. Led by Vercingétorix, the chieftain of the Arverni tribe and Camulogène, chieftain of the Parisii, the Celts rose against Caesar in 52 B.C. Camulogène died in the battle of Lutetia on the land which today forms the plain of Vaugirard in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. The rue Camulogène is named after him to honor his defense of what would become the city of Paris. A second battle took place on the site of the current Champs-de-Mars, on the Grenelle plain. There the troops of Camulogène were defeated by the Roman general Labienus. Vercingétorix was captured during battle and taken to Rome in chains, exhibited as a prize of Caesar’s successful conquest of Gaul, and executed six years later. With the defeat of Vercingétorix, the Roman subjugation of Gaul was complete. The Romans renamed the city Lutetia Parisiorum (Marsh of the Parisii) which gradually evolved into Lutetia, and later, Parisius.

The Romans established a new city on the Left Bank of the Seine, now Sainte-Geneviève Mountain. It comprised the high ground above the floodplain and marshland, between what is now the Panthéon and the Luxembourg Gardens where rue Saint-Jacques and rue Soufflot meet. Rue Saint-Jacques is considered the oldest street in Paris. If you view Paris from any high point on the Right Bank today, or the Île de la Cité, you’ll see the dome of the Panthéon rising majestically on this hill. The rue Saint Jacques was the Cardo Maximus (north-south axis) of the Roman city which ran all the way to Spain and north to Senlis, a commune on the edge of the Chantilly Forest. A second road, the present-day rue Galande, entered from Italy, passing through Lyon, Beauvais, Rouen, and the Normandy coast. Linked by the Decamani Maximii (a grid of perpendicular east-west streets), this street plan remained at the core of Paris through the Middle Ages.

From 53 B.C. to 212 A.D., the Romans built an arena, thermal baths, an aqueduct, and a forum– vestiges of which remain today. They also rebuilt the first wooden bridge over the Seine, originally constructed by the Parisii. The Petit Pont, as it is now called, spans the small arm of the river between the Île de la Cité and the Left Bank. The Arenas of Lutetia (Arènes de Lutèce), located in the 5th arrondissement, was a major center of the city where people went to watch games, gladiatorial contests, plays, and concerts. It was the largest amphitheater in Roman Gaul and could seat more than 15,000 people. Discovered in 1860, the movement to preserve the area was championed by Victor Hugo. Today, the space is a park where only a fraction of the amphitheater is visible, its remains long since buried or carted away. An arched walkway leading to the park is found at 49 rue Monge.

You can also see parts of the Thermae Lutetia (Thermal Baths) at the Cluny Museum, located in the Left Bank’s Latin Quarter. The baths are the preserved part of a much larger spa complex (approximately 6,000 square meters) that went from boulevard Saint-Germain to rue des Écoles, and from boulevard Saint-Michel to the rue de Cluny. Typical of the Roman way of life, these baths were the preferred meeting place for the residents of the city. People came there to wash, relax, have their hair cut, read in the library, or simply meet friends. The spa complex also included a large, open-air gymnasium designed for exercising, wrestling, weight lifting, and playing ball games. One of the best-preserved rooms of the thermal baths is the frigidarium (cold room), an impressive space with a groin vault ceiling 50 feet in height. There is also a calderium (hot room) with traces of stucco decoration adorning the walls.

Arènes de Lutèce, remains from the Gallo-Roman era in Paris. Photo © Arenes de Lutece, Wikimedia (CC BY 2.0)

In use until the end of the third century, the thermal baths were fed by the aqueduct of Arcueil, south of Paris on the Wissous Plateau. An adjacent aqueduct was built in 1616 to bring these same waters into the Luxembourg Gardens. The baths had a sewer system which evacuated wastewater that flowed into a collector basin located under the boulevard Saint-Michel.

The rediscovery of the Forum of Lutetia dates from the excavations of Théodore Vacquer (1824-1899), a French archeologist and architect. Stones that came from the quarries of Saint-Maximin and Saint-Leu-d’Esserent in the Oise department south of Creil were transported to this site by river barges. The Forum covered boulevard Saint-Michel, rue de la Harpe, rue Saint-Jacques, rue Cujas, and part of rue Soufflot. Its large, underground interior square would have been surrounded by a crytoporticus (gallery) of colonnaded porticoes decoratively concealing shops. A basilica rose in the eastern part along rue Saint-Jacques, housing the financial, legal and administrative quarters of the city. Visitors would have entered the basilica through the current rue Victor-Cousin.

In the 18th century more remains of the Roman city of Lutetia were discovered under the nave of Notre-Dame cathedral, which itself was built on the site of a Gallo-Roman temple. The Nautea Parisici (the Pillar of the Boatmen)– a monumental, Gallo-Roman, cubic column 5 meters high, sculpted from Oise stone– was decorated on all four sides with bas-reliefs depicting both Gallic and Roman deities. The pillar was erected in honor of Jupiter during the reign of Emperor Tiberius (42 B.C. – 37 A.D.), and is the oldest indigenous monument currently housed in the frigidarium at the Cluny Museum.

Old texts attest to the 19th-century discovery of the foundations of a temple to Mercury on top of Montmartre. The exact location of this temple has been lost, but it was probably situated near the Moulin de la Galette. Texts also recall a temple to the Egyptian goddess Isis, worshipped by many Romans including the Emperor Hadrian (116-133 A.D.) was also found in the Left Bank at the future site of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

In the 1970s during the construction of a post office on rue Cujas, fragments of the Forum of Lutetia (columns decorated with fluting, parts of the eastern wall, and moldings) were unearthed and are now on display at the Carnavalet Museum. Gradually demolished between the third and fourth centuries, the stones of the Forum were quarried for new buildings. At the entrance to an underground car park constructed in 2001 at 61 boulevard Saint-Michel, there is a fragment of the eastern Forum wall encased behind protective glass. Another fascinating discovery of Roman ruins was made in the 1960s during excavations under the forecourt of Notre Dame. The depth of the ruins indicates how much Paris was built up over its history to protect it from flooding. Here you can see in many layers the well-preserved remains of a Roman house, a dock of ancient Lutetia, public baths and more.

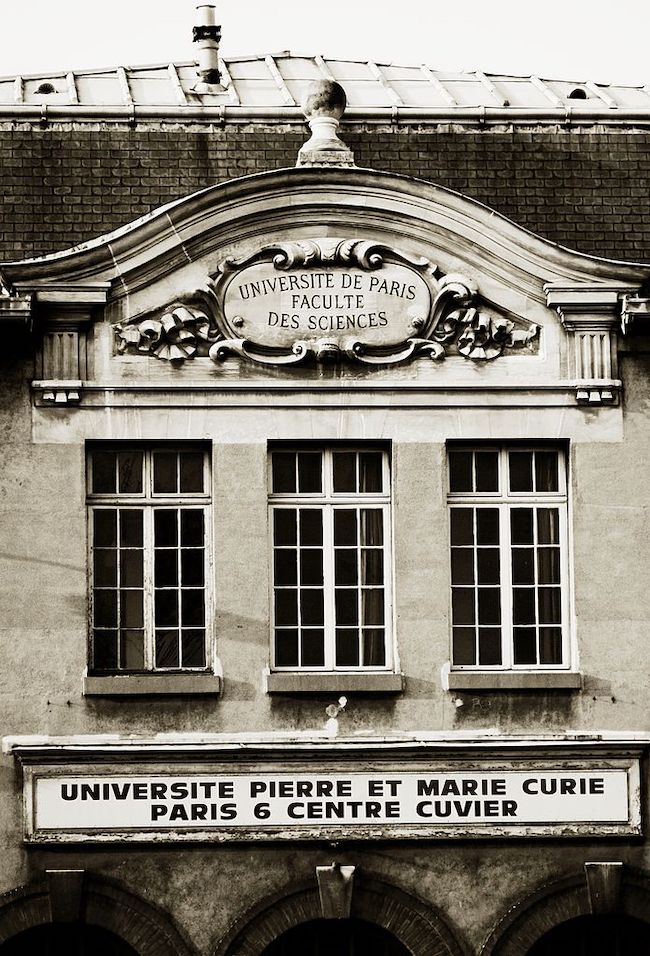

During expansion of the University of Pierre and Marie Curie, in May 2006, a Roman road and a city block were revealed. It included remains of private houses dating from the reign of Emperor Augustus (27 B.C. – 14 A.D.). Everyday items such as flowerpots, bronze chains, ceramics, and drawer handles were found there. The original owners were wealthy enough to own baths such as the ones found in one of the homes, a status symbol among Roman citizens.

Historic view of Pierre and Marie Curie University. Photo © Christophe MOUSTIER, christophe.moustier(a)free.fr, Wikipedia

At the Battle of Soissons in AD 486, the King of the Franks, Clovis I, defeated Syagrius, the last Roman governor, becoming the ruler of Gaul. Ten years later, Clovis renamed the city Paris and made it the capital of the Franks. He was responsible for uniting the disparate Frankish (German) tribes into one kingdom, called Francia, and established the most powerful Christian kingdom in western Europe.

Over 2,000 years ago Romans walked the streets of what is now Paris, but today visitors rarely look for evidence of the Roman conquest of Gaul. To see and learn more about the impressive relics from the past be sure to see the Roman collection at the National Archeological Museum and the Denon and Sully Wings of the Louvre. And for children there is Parc Asterix, dedicated to the Adventures of Asterix. Asterix is the beloved French comic book series that follows the characters of two Celts, Asterix and his best friend, Obelix, who have adventures while fighting the Romans during the reign of Julius Caesar.

Lead photo credit : The Panthéon, Paris. "To the great men the grateful fatherland". Photo © Hervé Seignole, Wikimedia (CC BY 3.0)

More in histoire paris, Paris history, Roman ruins

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY