Parisiennes and the Fight for Equality

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

There’s a deliberate exclamation mark in the title of the exhibition currently running at the Musée Carnavalet in the 3rd arrondissement: “Parisiennes, citoyennes!” It’s intended, say the curators, to invoke all the city’s women, to make them feel heard and included, perhaps even called to continue the struggle for equality. The exhibition tells the story of how civil rights for women evolved from the French Revolution until the Equality Act of 2000 and it pulls you in at every moment, with its unfolding array of photos, posters, manuscripts, film clips and artifacts. It is the history of the well-known women who fought for equality, but also of the many anonymous women who struggled alongside them.

Éventail suffragiste « Je désire voter », affichant le résultat d’un référendum organisé par Le Journal du 26 avril au 3 mai, ayant réuni 505 972 voix en faveur du vote des femmes, 1914 Maison Chambrelent et Croix successeur, éventailliste publicitaire Collection CPHB © Rebecca Fanuele

The story, told chronologically, gives a sense of the steady progress made towards equality for women since 1789, but it also conveys the “two steps forward, one step back” reality of the struggle. Laws passed just before the revolution limited women’s freedom significantly: all-female clubs were banned in 1793, followed in 1795 by a decree forbidding more than five women from gathering in public or from attending political meetings. Yet it was mainly women who marched to Versailles on October 5th, 1789 to protest about food shortages and high prices. Their success in forcing the king to return to Paris under guard was a trigger to the revolution which followed.

Branger, M.L., Grève des midinettes, Paris, 18 mai 1917, 1917, © Roger Viollet

But women were not the main beneficiaries of the new-found democracy in France. The Declaration of the Rights of Man made no specific mention of them. Two years later, Olympe de Gouges demanded equality in her Declaration of the Rights of Women, but her plea that women — who “had the right to be guillotined,” should also have “the right to debate” — was ignored. Indeed, she was guillotined herself during the period known as “La Terreur.” Under Napoleon, just a few years later, the Code Civil perpetuated male domination, ensuring married women had no rights over themselves or their children.

By the 1830s, the feminist Louise Dauriat was demanding to know whether Louis Philippe was king for les Françaises as well as for his male subjects and feminism took a step forward when La Femme libre, the first feminist newspaper, was published in 1832. Writers like George Sand were calling for equality in marriage and the right to vote for women. Imagine how they all felt in 1848 when universal suffrage was indeed brought in, but for men only. It would be almost a century until French women gained the same right in 1944.

Auguste Charpentier, Portrait de George Sand (1837 – 1839), 1837 © Paris Musées / Musée de la Vie Romantique

The section covering 1871-1914 is entitled Le temps des suffragettes and describes the Education Act of 1881-2 as a huge step forward, for it introduced free, secular schooling as compulsory for everyone up to the age of 13. One item on show is a poster announcing the opening of une école des deux sexes in the 5th arrondissement. At the same time, the École Normale Supérieure de Jeunes Filles opened in Sèvres, its mission being to train women to teach in girls’ schools and to have access to some entrance exams for the civil service. Note however, that the latter were not fully open to both sexes until 1976! In 1897, after much pressure from feminists, women were finally allowed to study at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris.

Better educational provision for girls led – of course! – to an increase in women in the professions, as lawyers, doctors and writers, and to talk of la nouvelle femme (the new woman) who was independent and proof that women could be equals. But many laws, and often public opinion too, made life difficult for them. The exhibition highlights the extraordinary campaign fought in 1887 against the law prohibiting women from wearing trousers. Paintings such as Jean Béraud’s Les cyclistes au bois de Boulogne, showing women wearing the smart and practical “bloomer” (culottes), are shown alongside caricatures which appeared in the press ridiculing this new trend. Alongside are comments by feminists who vowed to continue the fight for la réforme vestimentaire or “clothing reform.” Yes, it’s amusing on one level, but it’s also a clear reminder of the opposition women so often faced.

Jean Béraud, Le Chalet du Cycle au bois de Boulogne, 1900 © Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

The struggle for equality on such important issues as workers’ rights and the rights of women within marriage — the right to divorce was granted in 1884 — are highlighted, with an emphasis on some of the key women of the time. The journalist Caroline Rémy, known as Séverine, was the first French woman to earn a living from journalism and she wrote some 6000 articles calling for reforms. Hubertine Auclert, focused on demanding the right to vote for women, largely through her own publication, La Citoyenne, and through such radical acts as the withholding of tax and the disruption of elections. The key message was succinctly summarized by the feminist author and speaker Nelly Roussel, whose comment about a day designed to celebrate mothers with several children included the memorable words: “It’s not charity we want, it’s justice.”

Nelly Roussel et les comédiennes de «Par la révolte». Pièce écrite en 1903 [Paris, Salle des Sociétés savantes, 1er mai 1903]. Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand

Amélie Beaury-Saurel, Caroline Rémy dite Séverine, 1893 © Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

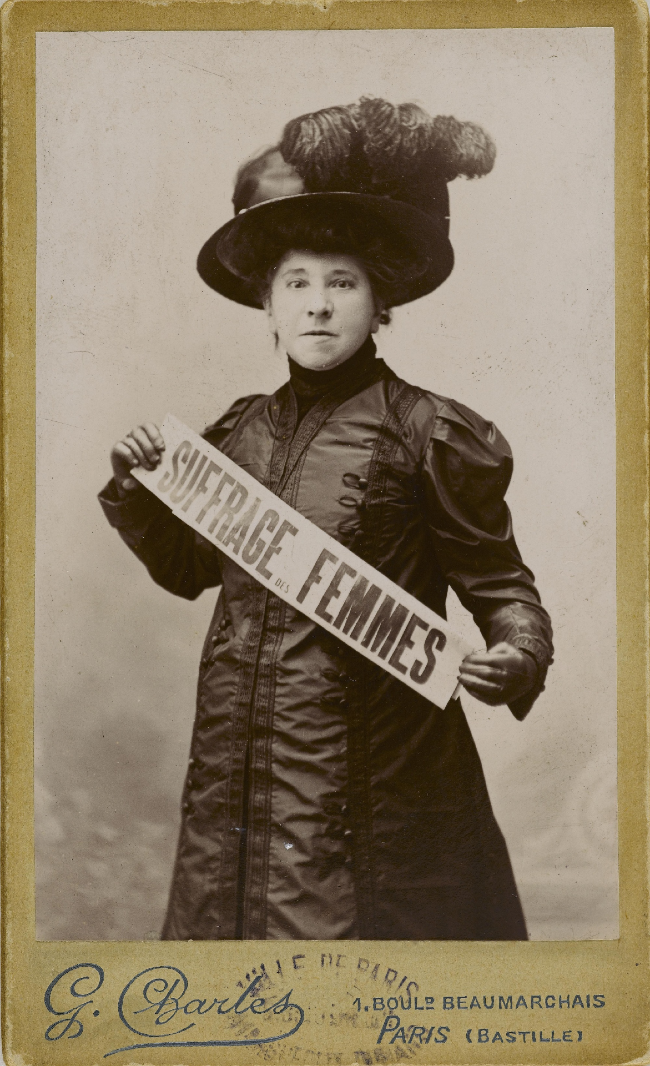

Charles, Hubertine Auclert tenant une banderole concernant le suffrage des femmes, vers 1890 Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand

Coverage of the period beginning with World War One emphasizes the major role women played in the war effort and their subsequent fury on discovering that, unlike in the UK, for example, French women were still not going to be granted the right to vote in 1918. There were some gains, such as a campaign in 1915 which resulted in a minimum wage for homeworkers — largely women of course — and a series of strikes by women in the garment and armaments industries demanding higher wages. The government eventually had to give in and this was termed a “victory for feminism,” but then came more retrograde steps. The so-called “return to the natural order” after the war saw stricter laws against abortion and an emphasis on encouraging larger families.

At the same time, some feminists became more vocal and more visible in society. Thousands joined associations like the National Council of French Women and l’Union Française which continued to campaign for votes for women. Some of the latter group attracted huge attention in Paris with their high-profile actions, blocking roads, chaining themselves to public buildings, burning copies of the Code Civil in public and disrupting elections. Lesbians like Sylvia Beach, the founder of the Shakespeare and Company bookshop, the novelist Gertrude Stein, and Natalie Barney, whose long-standing literary salon revolved around la culture lesbienne, were well-known figures in 1920s Paris.

Again in World War Two, women fulfilled many useful roles on the land, in the factories and in the Résistance, but, as a text in the exhibition puts it, “women were everywhere, but power remained with men.” A post-war baby boom did not help, despite the strident cries of Simone de Beauvoir whose book Le Deuxième Sexe was published in 1949, calling for economic and legal changes, sexual freedom and the right for women to control their fertility. In the 1960s, the march towards equality sped up: a first family planning center opened in Paris in 1961, a law authorizing contraception was passed in 1967, fashion allowed miniskirts, bare arms and even smoking in the street. The student unrest in May 1968 unleashed a cultural revolution which changed France forever.

Gisèle Freund, Simone de Beauvoir, 1948 Photo © Maison Européenne de la photographie / IMEC, Fonds MCC, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

The last section of the exhibition begins in 1970, when the Mouvement de Libération des Femmes (Women’s Liberation Movement) was founded and ends with the Equality Act of 2000. Key moments covered include the law legalizing abortion introduced by Simone Veil in 1975, the founding of various organizations to combat violence against women and the movements begun by groups of women for whom equality is even more difficult to achieve, such as immigrant women and black women. Studying this section, I couldn’t help reflecting that there is still more to be done. French women are still paid less than men, they are under-represented in vital areas like politics and the arts, and surveys show they do not always feel safe on the streets of Paris, especially at night.

Pierre Michaud, 6 oct 1979 Marche des femmes, Groupe de femmes assises faisant le signe « féministe », 1979 © Pierre Michaud / Gamma Rapho

The exhibition gives a comprehensive account of the role Parisiennes have played in their society over the centuries since 1789 and of the struggle which has been fought on so many fronts. I left in awe of the many women who handed the baton one to another down the last two and a half centuries, both the well-known and the unnamed, and grateful for what they achieved. Almost all of them led lives vastly more difficult and less free than my own. But it would be doing them a disservice not to mention that there are still areas where more needs to be done.

Details

The Parisiennes, citoyennes! exhibition is at the Musée Carnavalet until January 29th, 2023.

Musée Carnavalet

23, rue de Sévigné, 3rd

Nearest metro: St Paul or Chemin Vert

Tel: +33 (0)1 44 59 58 58

Open Tuesday – Sunday, 10 a.m. – 6 p.m.

Entry 11 €

Reduced entry 9 €

Free entry for under 18s

Entry to the museum’s permanent collection is free for everyone.

More in 3rd arrondissement, equality, exhibition, feminism, French feminists, musee carnavalet

REPLY

REPLY