The Fascinating Story of the American Hospital of Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Located in the western suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine, the American Hospital of Paris was founded in 1906 and is the only civilian hospital in Europe which receives neither government subsidies from France nor from the USA, depending solely on international donations, and remains to this day a nonprofit organization.

It was in 1904 that a certain Dr. A.J. Magnin, with American friend Harry Anton van Bergen, had the ambitious aim to create an association – the American Hospital Association of Paris – in order to offer American expatriates access to American-trained doctors in an American hospital.

Three years later, one year after Dr Magnin, Mr Van Bergen and seven other respected members of the American community had signed the founding act for the American Hospital of Paris, the chairman of the Board of Governers, John H. Harjes, signed the deed to a property in Neuilly-sur-Seine.

American Hospital of Paris in 2011. (C) CC BY-SA 3.0

In October 1909, the U.S. Ambassador to France Henry White, and the future president of the Republic Gaston Doumergue, inaugurated the new, 24-bed hospital. (The hospital now boasts 187 surgical, medical and obstetric beds.)

By 1913, the United States Congress had officially recognized the hospital, granting it federal status, which allowed the hospital to accept bequests and donations.

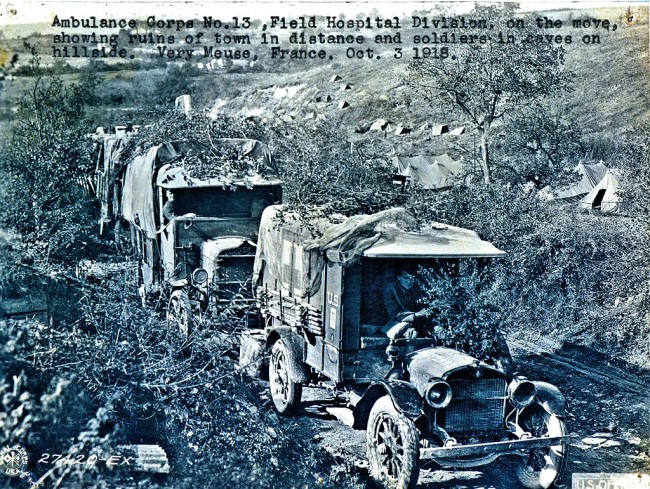

Montage for WWI. (C) Public Domain

It was, however, during the terrible events of WWI – The Great War – when the American Hospital cemented its place in the hearts of French citizens. At the beginning of the war in 1914, the USA was still a neutral country, but despite its neutrality, this large military hospital was offered to the French authorities alongside thousands of volunteers. An unprecedented flow of American donations followed. (It was estimated that nearly a billion dollars in today’s conversion rates was raised to finance the conversion of Lycée Pasteur, the ambulance fleet, field hospitals and humanitarian aid.)

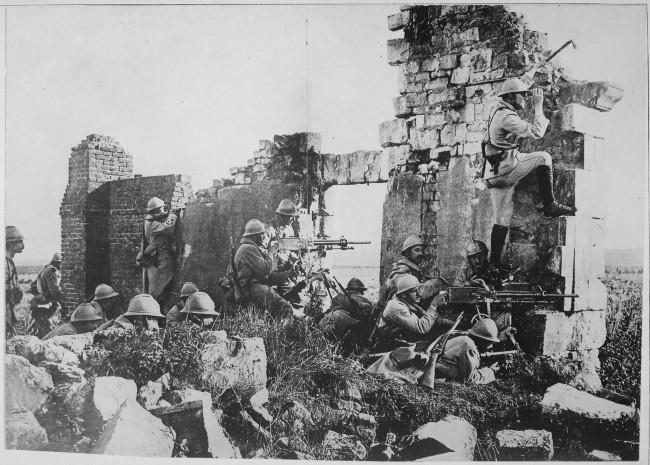

French infantry charge, 1914. (C) Public Domain

In 1914 after the Battle of the Marne, the American Hospital’s motor-ambulance corps was born. Ambassador Merrick had been informed of some 1,000 injured soldiers located 50 kilometers east of Meaux, completely stranded without any means of transport. Merrick immediately contacted everyone he knew who owned a car. In several runs, all the wounded soldiers were transported back to the American Hospital. This first frantic, impromptu convoy spawned the infinitely more organized American Hospital’s motor-ambulance corps.

Hospital’s motor-ambulance corps. (C) Flickr

In the following three years, countless numbers of doctors, nurses and ambulance drivers volunteered to treat and operate on hundreds of thousands of wounded persons.

The hospital, which had already expanded its bed capacity to 600 beds, soon found the need to increase this to 2,000.

In April 1917, America entered the war and as such was no longer a neutral country.

Nurses in WW1. (C) Public Domain

At the end of the war, in 1918, acknowledging the services rendered by the hospital to wartime France, the French government decreed the “American Hospital of Paris be recognized as an institution of public benefit.” As such, the hospital could now receive donations and bequests under French law.

It was not only during the First World War that the American Hospital of Paris was to prove its loyalty to France in immeasurable ways, but it was here where a staff surgeon stood up to Nazi invaders during the Second World War, becoming a hero martyr of the French Resistance. Dr. Sumner Waldron Jackson bravely dedicated himself to the lives of Allied fighters and was interned in the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg.

Paris – Avenue du Bois de Boulogne. (C) Flickr

When the Germans entered Paris on June 14th and their swastikas were hoisted over the Arc de Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower, Dr. Thierry Martel, Chief Surgeon at the American Hospital of Paris, committed suicide. Martel was a complicated man, both anti semitic and anti German. He was the son of French aristocrats who had loudly condemned Dreyfus and nouveau-riche Jews, but Martel’s son had been killed in the First World War and his hatred of Germans had led him to vow to never speak a word of German. To see their flags flying from public buildings and their soldiers in the streets of Paris was more than Martel could bear.

Dr Sumner Jackson took Martel’s place as Chief Surgeon, and as such was in a position to direct hospital policy. America, as at the beginning of WWII, was still a neutral country and Jackson wasted no time in sheltering downed British and American pilots.

Jackson was no stranger to France. In 1916 he had volunteered to join the British Army in France as a field surgeon and was almost instantly exposed to the unimaginable horrors of the Second Battle of the Somme. (He married a French nurse, nicknamed Toquette, who survived, but never fully recovered from her incarceration in Ravensbruck. She died in the American Hospital of Paris in 1968. She had been decorated many times; her awards included the Croix de Guerre and the Chevalier de Legion d’honneur.)

Both Jackson and his wife had found it hard to settle in the U.S. and both returned to France and the American hospital. Between the wars, Jackson treated illustrious patients such as Hemingway, Gertrude Stein and Scott Fitgerald, although the hospital was trying hard to throw off its elitist image.

The Second World War would tragically solve that problem.

French machine gunners defend a ruined cathedral, late in the war. (C) Public Domain

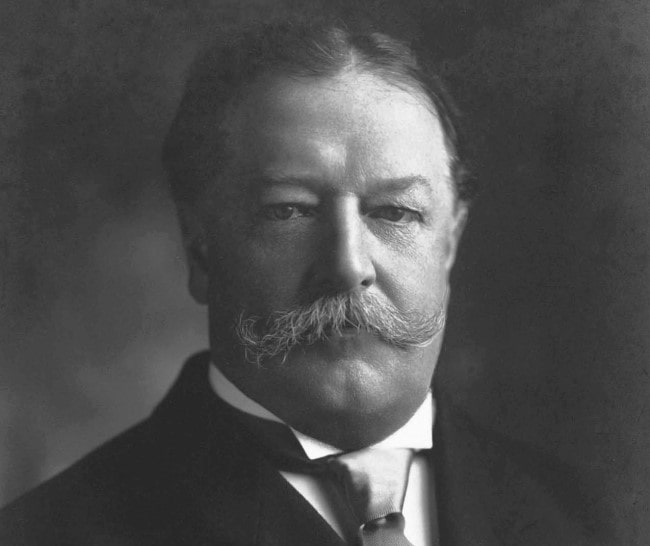

(There had been a clause however, signed into American law in January 1913 by President William Howard Taft, that the hospital was required to offer medical services free to American citizens in France. Wealthy Americans and foreigners, often including nobility, paid for private rooms, while Americans without funds were admitted to wards. Hemingway had his head stitched there when a skylight fell on it, and also his appendix removed. The notoriously hard-up James Joyce was generously made an “honorary American” to enable him to receive free eye surgery in 1923, and Zelda Fitzgerald benefitted from Dr Martel’s surgery for her various gynecological ailments.)

William Howard Taft, 27th President of the United States. (C) Public Domain

At the beginning of the war the Germans were not averse to wounded Allied POWs being treated at the hospital as it saved them the cost of looking after them. But Jackson was not content with sticking to medical procedures and began falsifying documents for American, English and French prisoners to show that some of these prisoners had died when in effect they were on their way to England aided by members of the French Resistance, traveling via the Pyrenees to Spain and thence to Lisbon. Jackson kept this up for four years under the noses of the Germans whose headquarters were stationed directly opposite the gates of the hospital. He worked day and night, not only at the hospital but also in the field, at often basic dressing stations in Châteauroux and in the casino south of Fontainebleau. Jackson often gave his own blood; amputations were common and Jackson was once impelled to amputate a wounded French soldier’s leg in the dark. The amputation was a success, with a prosthetic attached later.

Jackson’s experience during the Great War meant he had seen and experienced everything possible that could be done to man in war time, and he simply got on with the never ending, bloody job of trying to repair broken bodies. Despite sometimes the seemingly hopelessness of the task of treating thousands of prisoners, Jackson found time to rail at the authorities for failing to distribute American aid intended for the prisoners. His famous accusation was aimed at “the bullshit bureaucracy of old men.” The hospital became more than a place of treatment, though, as the French POWs had inevitably precious intelligence data on the locations, security measures, and sizes of all the German camps in the Paris region.

A report prepared by the American Hospital for its U.S. governors stated among other things, that “Too much praise cannot be given to Dr. Sumner W. Jackson.” The report was written when the Germans first entered Paris. Jackson had hardly begun his heroic work.

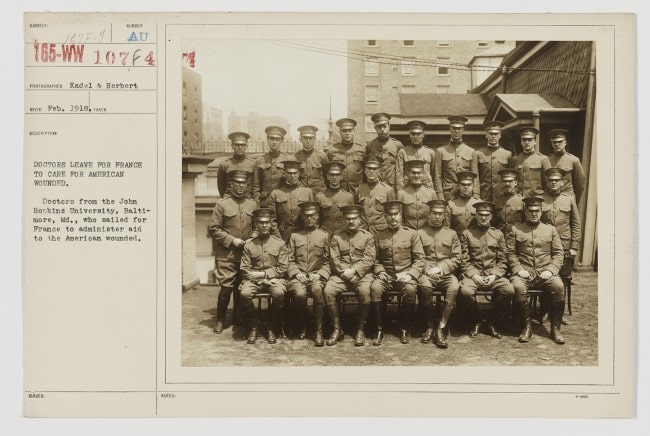

Colleges and Universities – Johns Hopkins – Doctors leave for France to care for American wounded. (C) Public Domain

A year before the war ended, Jackson’s luck ran out. He was arrested with his wife and his 16-year-old son. Jackson survived starvation, beatings, torture and forced labor in SS prisons in France and Germany before being transferred to the concentration camp for political prisoners in Neuengamme. Forced to work 14 hours a day at a munitions factory, Jackson endured it all with dignity and an extraordinary stoicism that never wavered. In an horrific twist of fate, the SS, discovering that the British Army had reached the outskirts of the town, crowded the 9,000 barely alive prisoners onto freight cars and shipped them to the port of Lübeck where they were transferred aboard ships. (The remaining 3,000 prisoners in the camp were murdered.) Jackson and his then 17-year-old son Phillip were together on one ship. On May 3rd, the RAF, unaware that the ships were crammed with prisoners, bombed and strafed the ships when their captains refused to return to shore.

Neuengamme prisoners working on a canal of the Dove Elbe. (C) Public Domain

Phillip Jackson survived, only one out of 600 survivors. The body of Sumner Jackson was never recovered. The war officially ended five days later.

The American Hospital of Paris continues to thrive to this day, with enviable facilities and an enviable reputation. The Outpatient Consultation Department alone boasts 150 physicians who cover every major medical and surgical speciality and provide care for patients 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In all, the hospital’s medical staff numbers over 500 physicians specializing in every conceivable condition.

It would be impossible for the hospital not to attract the rich and famous. Rock Hudson received his first treatment of the AIDS drug here in 1985. Aristotle Onassis died here in March 1975; Jean Gabin, Francois Truffaut, Tino Rossi, Bette Davis, Pamela Harriman, the United States Ambassador to France, France Gall, Karl Lagerfeld and Pierre Cardin breathed their last breath in the American Hospital of Paris.

But perhaps the legend that deserves to live on more than any other is that of Dr. Sumner Waldron Jackson, who not only saved countless lives at the American Hospital of Paris, but ultimately gave his own life for it.

Lead photo credit : American Hospital of Paris. (C) Public Domain

More in concentration camp, Doctors, French Resistance, Hospitals, soldiers, World War II, WW1

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY