Marking Armistice Day with Films on the Great War

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

On the 101st anniversary of the Armistice, two French films that chronicle the immediate aftermath of the First World War come to mind. Life and Nothing But (1989) by French director Bertrand Tavernier, and A Very Long Engagement (2004) by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, are astounding cinematic works that recreate the struggles of young women trying to find their loved ones missing in action long after the declaration of peace in 1918. Grief is their overriding theme, yet tempered by the hope each of the female characters carries with them.

Life and Nothing But is set near the Verdun battlefield in October of 1920. Tavernier focuses on the contrasts that permeated life in post-war France at this time: the disparity between the rich and poor, men’s roles opposed to women’s, bureaucracy versus truth. The film centers on Major Delaplane, a French army officer (played expertly by Philippe Noiret) who has the sad task of identifying both the thousands of French soldiers living anonymously in military hospitals and the dead soldiers whose remains are strewn across the war-torn countryside. His path crosses those of two women, the haughty aristocrat Irene and the naïve country girl Alice, who are both absorbed in the hunt for their missing loved ones.

Madame Irene de Courtil is trying to locate her husband by visiting military hospitals along France’s north coast. In one hospital full of unidentified wounded and shell-shocked men, she meets Major Delaplane.

Delaplane is obsessed with statistics; he knows all too well that more than three hundred thousand French families do not know whether their loved ones are missing or dead. At the hospital the Major poses the nameless for their identity photographs, but he must also record the dead in order to satisfy the soldiers’ families. The reality that the French officials don’t want to admit is many will never be found.

Alice, a young schoolmistress, who has lost her job to a returning soldier, is looking for her fiancé. She now serves in the village café patronized by rootless soldiers as well as families desperately searching for information or proof that their loved ones are still alive. A photo wall of the missing is spontaneously created there. Frustrated by military red tape, citizens begin the search for their loved ones themselves.

In reality, the French government, through entities like Delaplane’s Search Bureau, endeavored to identify soldiers via scraps of uniform and personal effects. The families too on Tavernier’s war torn fields, are frantic for any scraps to hang onto. These families battled through lines of bureaucracy to find remnants of their loved ones in the mud; anything: a tin cup, a toothbrush, a button. The director shows us how desperate they are for any token that might tie them to their loved ones, whether the bond was real or imagined.

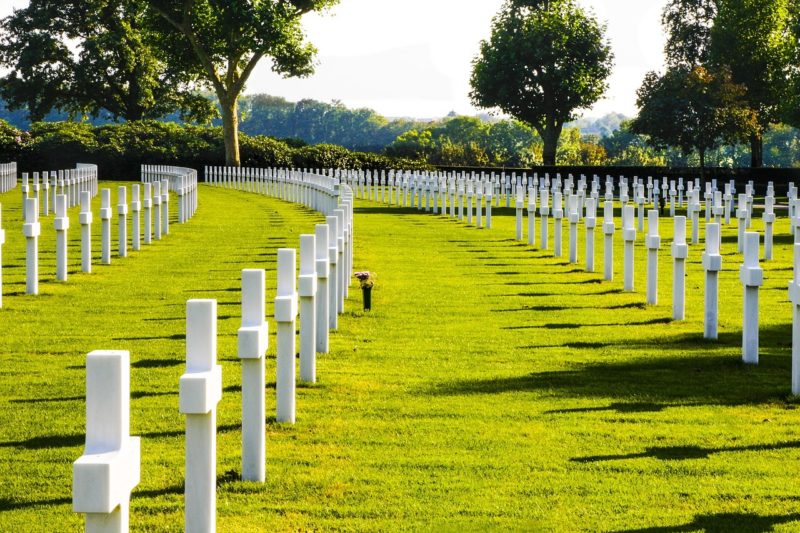

Cemetery War. Taken by GiselaFotografie. Image © Needpix

Alice and Irene realize they are wasting their lives by searching for ghosts. Along with the thousands of other families searching for the Missing in Action, they will have to learn to move forward without their loved ones. Alice’s new suitor, rebuffed because she says, “she is not free,” shouts at her to, “Go find your stiff… they can go to hell because I’m here.” The very title Life and Nothing But is a philosophy of how to love again in the post-war world.

Jean-Pierre Jeunet must have been influenced by Tavernier’s Life and Nothing But; the similarities between the subject of the two films is so striking. Straight off the heels of Amelie, Jeunet’s triumph at the box office allowed him the resources and time to adapt the Sébastien Japrisot novel Un Long Dimanche de Fiançailles for the screen. Unfortunately this absolute masterpiece did not receive the same box-office recognition of Amelie.

Evolving into a detective story and a romance, A Very Long Engagement is set in the years after the Great War ended. Mathilde, a 20-year-old with a limp and an iron resolve, is played by Audrey Tautou. Mathilde refuses to believe her fiancé was executed as a traitor. As in Tavernier’s film, bonds, real or imagined, are important. Mathilde always imagines a wire or a lifeline to Manech. If he was dead, she said, she would feel it. She is entrusted with a wooden chest of keepsakes to uncover each of the characters – perhaps survivors – that knew her gentle Manech in his final days in the trenches. In this way she unravels the stories of each of the six other condemned men but she must retie them to find her boyfriend.

With the help of her aunt and uncle, her family trustee and a private investigator, named Germain Pire, the Peerless Pry, she continues to untangle the mystery surrounding Manech’s disappearance. In post-war France investigators specializing in military disappearances were like vultures, seeing an opportunity to make money from the grieving. Luckily for Mathilde, the Peerless Pry’s daughter has been affected by polio and feels a kinship with the fiancée.

A Very Long Engagement movie poster. Image © Moon, stars and paper

Célestin Poux, The Mess Hall Marauder, convincingly played by the French actor Albert Dupontel, arrives on his British motor bike and helps put the pieces into place. Through red mittens and German boots, and the stories and flashbacks of each of the poilus she encounters, the mystery is solved for the audience. Each of their threads or “wires” reconnect to reveal a bitter-sweet ending.

Tautou is surrounded by the familiar faces of Jeunet’s rotating cast of actors. Dominique Pinon is her uncle, André Dussollier is her family’s trustee, and Tcheky Karyo is the Peerless Pry. Marion Cotillard is featured as an ever-so vengeful black-widow. Jeunet’s art director Aline Bonetto creates the world of 1920 with amazing detail.

After the ink had dried on the Armistice of November 11, 1918, life carried on. These two movies reiterate that for the hundreds of thousands who never knew the final resting place of their loved ones, that life would be a hard and haunted one.

Lead photo credit : French military hospital during the First World War. Public domain/ wikimedia commons

More in Armistice Day, Great War, WWI