Camille du Gast: The Legendary Daredevil of the Belle Epoque

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“The danger of an accident is always present in my mind, though I am never afraid.” – Camille du Gast, Motor Monthly, Dec. 1903.

Camille du Gast was one of the richest and most accomplished women in France. A celebrity of the Belle Époque, she was an accomplished sportswoman: a balloonist, parachutist, fencer, skier and a racer of both motor cars and motor boats. Fear was a stranger to her.

Camille du Gast was the second female member of the Automobile Club of France. She was the president of the French society against cruelty to animals and campaigned vehemently against bullfighting. Shockingly named as the Femme du Masque in Henri Gervex’s infamous nude painting, Madame du Gast found herself embroiled in scandal. She devoted herself to the rights of women, yet own daughter colluded to have her murdered.

Camille du Gast in a Panhard & Levassor car at the Paris-Berlin 1901, with Prince of Sagan. © Jules Yvon/ Wikimedia Commons

She was born in 1868, as Marie Marthe Camille Desinge, but material about Camille du Gast’s early life is scarce. Her father was a confectioner and a Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur for his work in the National Guard. Camille grew up as the much younger sister of Alfred and Irma. She was reputed to be an accomplished musician with a lovely soprano voice.

In 1889, a romance prompted Camille Desinge to flee her home at 71 Boulevard Strasbourg. Unafraid of social morals of the time, Camille began living with Jules Crespin, the very young and very rich heir to Dufayel, one of the largest department stores in France. According to the Archive de Paris, their only daughter, Diane Marcelle Lucille Crespin, was born out of wedlock on October 1, 1891. Official records show the couple didn’t solemnize their union until October 12, 1894. Just 26, Jules died the following year. During their short time together, they lived in Paris at the still-remarkable 106 rue Lauriston in the 16th arrondissement. The origin of the added “du Gast” is lost in time.

Camille du Gast developed a taste for adventure while Jules was still with her. Avid hot air balloonists – Jules owned two – they frequently launched them to advertise his business. Camille went a step further. A British news report from June 1895 erroneously labels du Gast as an actress, but describes how she ascended over Paris with well-known aeronaut Louis Capazza in his aerostat, a balloon/parachute hybrid. Capazza and du Gast managed a successful 2,000-foot parachute decent over Faubourg Saint-Antoine.

Camille du Gast was at loose ends after her husband died. As a young widow, she was equally described as elegantly handsome or stunningly attractive. Blonde and buxom, her figure was compared to the Venus de Milo. Men found her sense of humor and magnetic smile irresistible. Her idealism, independence and ambition led to her being both admired and envied.

Camille du Gast. Publicity photo for piano recital. Public Domain

Automobile racing is what Camille du Gast is most remembered for. In 1900, she was so besotted with racing after watching the Gordon Bennett Cup that she purchased a Peugeot and a Panhard et Levassor for herself. In 1901, she was one of two women entered in the Paris to Berlin endurance race. The bonnet of Madame du Gast’s car was strewn with flowers as she moved from town to town. Helie de Talleyrand-Perigord accompanied her as her mechanic, but in her many races she acted as her own mécanicienne, quickly replacing her tires, assisted by Helie only if two hands were necessary. Du Gast said, “I have full control of my car. I feel that she obeys me. …You know it almost like you know yourself.” She started dead last but finished 22nd in a field of 122 entrants, making it to Berlin in 25 ½ hours, where her speed and her looks brought the sobriquets “the Valkyrie of the Motorcar” and “l’Amazone.” The press waxed poetic about her beauty, comparing Camille to the Empress Eugenie and any number of Greek goddesses.

Camille du Gast, Paris-Berlin, 1901. Public Domain

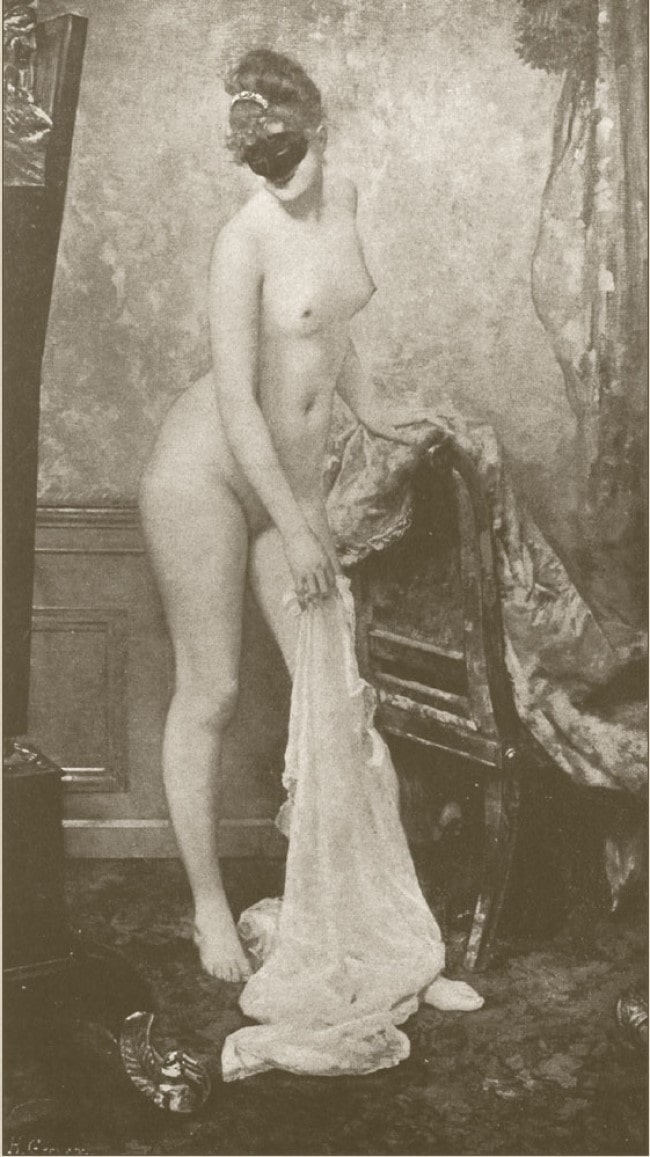

In 1902, Camille du Gast’s own family maliciously accused her of having posed nude for Henri Gervex’s La Femme au Masque. Painted in 1885, when Camille would have been just 16, Henri Gervex’s painting is a risqué image of a nude woman wearing only a domino mask to hide her identity. Du Gast had been in court, embattled with her estranged family over an inheritance dispute. To damage her reputation, Barboux, her father’s lawyer, distributed photos of La Femme au Masque throughout the court and claimed the mystery woman was Camille. Her father said he found the mask in her belongings.

La femme au Masque by Henri Gervex, 1885. Public Domain

With a different battle on her hands, Camille du Gast sued Barboux for defamation. Ironically, the model for the painting was known. Marie Renard had posed for not only Gervex, but also Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot. Both Renard and Gervex testified on Camille’s behalf, but she still lost the case. After the ruling, her companion Helie got into a slapping match with Barboux. To add insult to injury, he was prosecuted too.

In 1903, with her peaked cap and her indispensable googles, Camille du Gast set off on the chaotic Paris to Madrid Race. Unbeknownst to the 207 racers, this competition would turn into a calamity. Branded as the Race of Death, two drivers and six spectators were killed in an accident near Bordeaux. Du Gast was in 8th place, but her conscience wouldn’t let her drive past fellow driver, Phil Stead, who was pinned under his car. She struggled him free and tended to him until an ambulance came. The French government stopped the Paris to Madrid race at Bordeaux. Cars were impounded, keys taken away and returned to Paris by train.

In 1904, the Benz factory team offered du Gast a spot because of her steely performance in the cursed race. She’d had been able to stomach the violence of a car crash, yet got back behind the wheel. However, that carnage impelled the French sports commission to bar women from competing for the reason of “female excitability.” Du Gast said that no such unchivalrous act had been committed since the French beheaded Marie-Antoinette. She was determined to enter the transcontinental race from New York to San Francisco. Surely, the broad-minded, large-hearted Americans would never discriminate against a woman. She was apparently unaware of the ACA’s all-male membership.

Unable to race automobiles, du Gast instead took up motor boat racing. It was such a new sport that no one questioned her “feminine excitability.” Late in the season in 1904, she attracted the eye of the media with her attire – a tightly-cinched corset over her full-length leather coat, gloves, and an elegant hat with a veil and bobbing violets.

Camille du Gast, 1904. Public Domain

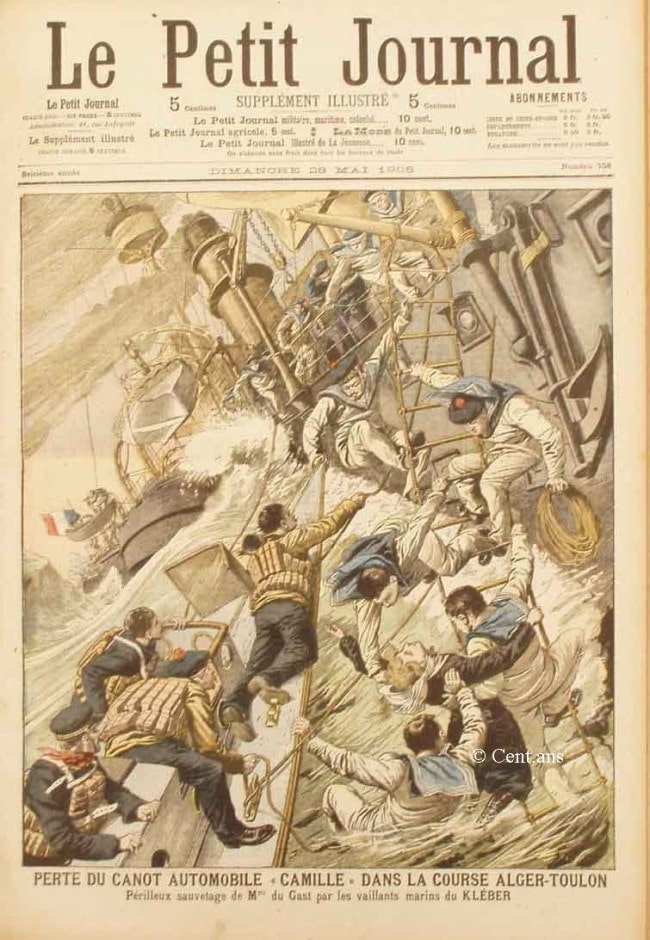

In April of 1905, du Gast raced her boat, La Turquoise, at the meet at Monaco. The following month she took part in the open sea Algiers-Toulon race and disaster struck again. In the lead, du Gast was caught in a tremendous storm. The rest of the field was decimated; the boats of six of the seven entrants, including du Gast’s, sank. The heavy seas tossed her eponymously named boat. The Camille’s bolts gave way and water flooded the engine room. A ship trying to tow Madame du Gast’s irreparable boat gave up after two hours. Le Figaro’s correspondent quoted du Gast on May 15, 1905 saying, “I shook hands with all my companions, and we awaited our salvation.” Salvation came in the form of the destroyer, Kléber. Thinking they too had abandoned her, she “made the sign of the cross thinking that the end had come.” When the Kléber managed to maneuver alongside, a sailor lowered a rope ladder to Madame de Gast, but she refused to leave until her crew were secure. When du Gast attempted to climb to safety, she was tossed into the sea. A crew member (who was later handsomely paid) immediately jumped off the deck of the Kléber keeping du Gast afloat until she was secured in a life preserver.

Camille du Gast, the Valkyrie of motorsports, on board of the Kléber. © https://blog.imagesmusicales.be

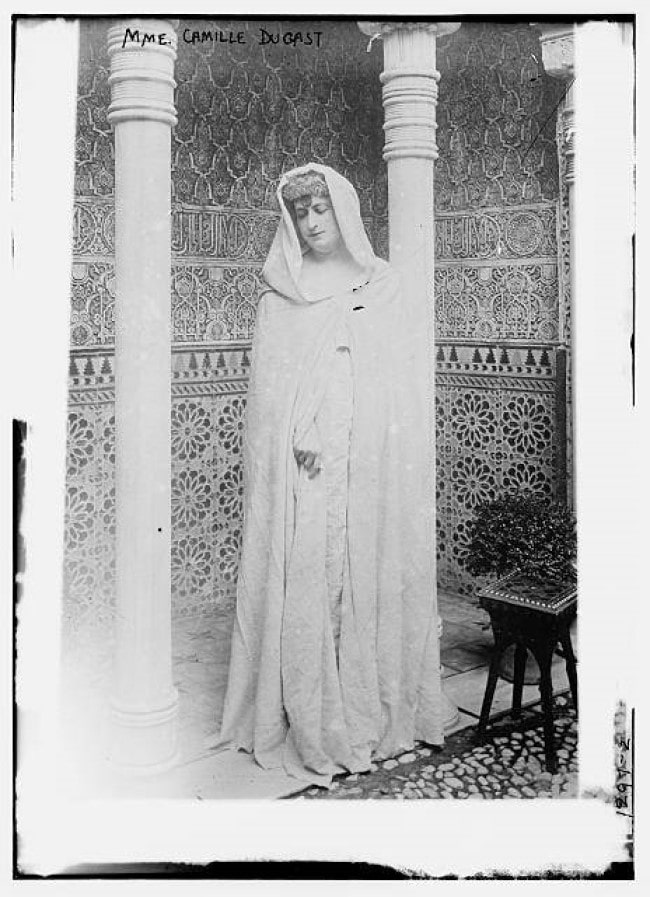

Not to be deterred, du Gast continued her sporting adventures. An accomplished rider, in 1906 she decided to explore Morocco, traversing the desert on horseback, a journey which she described in Ce que m’a dit le Rogui, published in 1909.

More family troubles caused her to pull back the reins. The diabolical plot of her own daughter ended Camille’s bravado. The avaricious Diane had been long attempting to extort money from her famous mother. Du Gast narrowly escaped a nighttime assassination attempt by her daughter’s ruffian cohorts at 12 rue Leroux. She confronted them and they fled. Faced with a daughter who had deceived her, nothing was the same for her after that.

She threw herself into all kinds of municipal reform. She was president of Parisiens du Paris. As one of the objectives of her society was the beautification of Paris; in 1910 she was daring enough to suggest the removal of the Eiffel Tower!

Camille du Gast, rescue during the Alger Toulon race, Le Petit Journal, 1905. Public Domain

In 1910 and 1912, the French government commissioned du Gast to visit Morocco again, where she worked with the local women distributing medicine and giving sweets to children. Her mission was to help the French government gain positive influence over the country. Du Gast felt that she had improved the image of France in the eyes of the Moroccans, and had won their respect. Whether or not it was necessary, she and an armed guard penetrated the outlying regions of Fez, to teach locals how to properly cultivate their virgin and neglected lands.

After making more than five visits to Morocco, Camille du Gast returned to Paris with wild animals for the collections at the Jardin des Plantes. After the betrayal of her daughter, she steadily became more devoted to animal welfare. Du Gast served as president of the Société Protectrice des Animaux (SPA) for three decades. Du Gast began establishing centers for orphans and impoverished women. A self-declared feminist, du Gast sought to advance the rights and emancipation of French women. After World War I, she became the vice-president for The French League for the Rights of Women. She wasn’t afraid to have her voice heard.

Camille du Gast in Morocco, circa 1910-12. Public Domain

Du Gast actively campaigned against bullfighting – illegal yet tolerated in France. She took a phalanx of 600 young people with her to the picturesque town of Melun, where news reports from June 1930 revealed that rioters clashed with an attempt to stage a three-day program of Spanish-style bull-fighting. Concerned with cruelty to the bulls and horses, du Gast’s rag-tag army took possession of the streets, vigorously booing the toreadors when they arrived. A hundred of her young men and women entered the bullring and linked arms to prevent the fight. The bull retreated and pandemonium broke loose. Gendarmes struck out at the demonstrators with whips and sticks. The bull was brought back in after the pronouncement there would be damage done to him, but the demonstration continued. Choking smoke bombs were thrown into the arena. Spectators soon became involved in physical and verbal conflict, and above the din, was the voice of Madame du Gast urging her followers.

Du Gast suffered through counter cries in favor of the fight. The mildest were, “Throw her out! Whip her! Throw her to the bull.” The cheated crowd demanded a real fight or else they would torch the place. In the streets, the opposing factions batted for two hours without cease. Leading her troop back to Paris, du Gast appealed to the government ministers who nixed the next two days of bullfighting.

Du Gast published several articles about her sporting achievements, including “A deux doigts de la mort” (On the Brink of Death), describing the disastrous Algiers to Toulon race. She published several travel narratives, and wrote the preface to Gustave Dumaine’s 1933 book, Contes pour mon Chien (Stories for my Dog).

Camille du Gast continued her charitable work during the German occupation of Paris and continued to live there helping the disadvantaged until her death in 1942. Camille du Gast is interred in the Crespin family tomb at Père-Lachaise Cemetery. The rue Crespin du Gast, in the 11th arrondissement, is one of the very few streets in Paris named for women.

Crespin Family Tomb. © Wikimedia Commons

“I inhale with every breath a profound sense of satisfaction and feel that life is really worth living.” – Camille du Gast, Motor Monthly, Dec. 1903.

Lead photo credit : Camille du Gast, Paris-Madrid Race, 1903. Public Domain

More in Automobile Club, Camille du Gast, Motor Racer, Sportswoman, Trailblazer, Women of Paris

REPLY