Julie Manet: Daughter of Berthe Morisot and Niece of Édouard Manet

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The exhibition entitled “Julie Manet, An Impressionist Heritage,” which runs until March 20th at the Musée Marmottan Monet, is so exceptional — with over 100 paintings, sculptures, pastels, watercolors and engravings — that the museum has dedicated the entire first floor, the Rouart Galleries, to its display.

courtesy of Musée Marmottan Monet

This extraordinary collection has been amassed from museums and private collections all over the world, many pieces seen for the first time in public, and showcases Julie Manet’s life-long mission— alongside her husband Ernest Rouart— of highlighting the art of her mother Berthe Morisot, her uncle Edouard Manet, and the other Impressionists she was so close to from childhood.

Julie Manet and her husband began collecting Impressionist paintings almost immediately after their marriage. Julie, as Berthe Morisot’s only beloved child, had been left not only her mother’s paintings but also those Morisot had either been given or had purchased herself.

Édouard Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets (in mourning for her father), 1872, Musée d’Orsay.

No other child, herself the daughter of a superbly talented and respected painter, could have been so immersed in Impressionist art, so intimate with the painters of that era, as Julie Manet. Her love for her mother and Impressionism resulted in a lifetime dedicated to keeping her mother’s legacy alive, promoting both the work of Morisot and her contemporaries like Manet, Renoir, Degas, and Monet.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies © Wikimedia Commons

As an artist Julie never gained her mother’s acclaim, nor did she aspire to her mother’s talent and recognition, but the parallels between them are notable.

Berthe Morisot was part of a very supportive family. She was especially close to her sister Edma, another artist, and both had intended to dedicate their lives to art. They had the advantage of belonging to a middle-class family where money was not a problem. They had the disadvantage, however, of the same middle-class family anticipating that their daughters would make suitable marriages. Painting was fine as a pastime, a genteel hobby, it was even to be applauded, but as a profession, instead of marriage? That was an entirely different proposition.

Berthe Morisot, The Mother and Sister of the Artist – Marie-Joséphine & Edma, 1869/70

There were very few acknowledged female painters of the time. Eva Gonzalès and Mary Cassatt were two of them. But even though Cassatt was American and not entrenched in French customs, her mother and family friends still accompanied her as chaperones to Paris where she studied with private tutors (since the Ecole des Beaux-Arts was still not accepting female students). Even the fashionable ‘Cercles Artistiques,’ a pre-cursor of the Impressionists which had initiated the private alliances of independent art exhibitions, showed only their members’ work — and even they did not admit women. Likewise, the Association of Friends precluded females. Both these artists, like Morisot, had supportive and sufficiently affluent families to enable them the wherewithal to paint along with the expert private tuition. (Marie Bracquemond, on the other hand, had limited resources, but her talent had been recognized by Ingres who invited her to work in his studio. Unfortunately Bracquemond was soon disillusioned by Ingres’s attitude towards female painters of whom she said, “he doubted the courage and perseverance of a woman in the field of painting…He would assign to them only the painting of flowers, of fruits, of still lifes and genre scenes.” Bracquemond joined the Impressionists producing large-scale paintings of women, often en plein air. Despite several of her paintings being accepted by the Paris Salon, she gave up painting altogether after 1890. Her husband, the fellow artist Felix Bracquemond, disapproved of the Impressionist movement and had actively discouraged his wife’s career in art.)

Eva Gonzalès, Plage de Dieppe vue depuis la falaise Ouest. © Wikimedia Commons

Mary Cassatt, Portrait of Madame Sisley, 1873. © Wikimedia Commons

It was rare enough for a woman to succeed in an artistic career with support, but doubly hard to have a hope of success without it. (Suzanne Valadon, of course, ignored all these norms and was a shining star of perseverance against all odds, where her talent, bloody mindedness and an indomitable spirit broke through every societal barrier.)

It seems unlikely, though, that had Berthe Morisot lived long enough, that she would have pushed her daughter Julie into marriage. Marriage that Morisot herself had fought against until she reached the then very “spinisterish” age of 33.

Berthe Morisot. Unknown author. Public domain

Morisot had been dismayed when her sister Edma’s marriage had effectively finished off any aspirations of Edma becoming a serious artist, and it had only served to harden Morisot’s resolve to never marry. But despite Morisot’s close friendship with Edouard Manet and her inclusion in the circle of Impressionist painters, the restrictions in the 19th century for a single, unmarried woman were still formidable. Marriage and motherhood were the only real accepted convention for bourgeoise women. Only men could be geniuses; only men could be brilliant artists. After all, where was there a single painting by a woman in the Louvre? The belief that women were to be protected, chaperoned, and their reading matter censored all bore down heavily on Morisot. Her mother proposed suitors for her, but it was Morisot herself who had decided on Eugène Manet, Edouard’s brother, as her husband. Her choice was inspired, and one Morisot would never live to regret.

(Almost inevitably when there is a close friendship between the sexes — and Morisot was certainly one of Edouard Manet’s favorite subjects — there has been speculation that their friendship was more than artist and sitter. While Manet’s track record of infidelities cannot be denied (he died from syphilis. like his father), Morisot was fastidious by nature and also highly chaperoned. Although she never disguised her admiration for Edouard Manet, it seems unlikely that that particular line was crossed and that Eugène was simply a poor second choice. It was true however, that after Morisot’s marriage, she never modeled for Manet again.)

Edouard Manet, Julie Manet sitting on a watering can © Wikimedia Commons

Although a proficient enough painter, Eugène Manet had never considered it a profession and was unlike his brother Edouard in almost every way. A quiet, private man, his unwavering support for his wife’s artistic career was exemplary. He had recognized her talent, and doubtless also fallen in love with her beauty, and with a rare unselfishness promoted her work above all else. From their letters, it is obvious that Morisot loved Eugène just as much, and appreciated everything he did, not only for her, but also in supporting the burgeoning Impressionist movement. (At first Morisot’s mother Cornélie was diffident about the marriage, and concerned enough to voice her disapproval — the Manet family were wealthy enough that Eugène did not need to work and Cornélie found this lack of career as a moral failing. However, Cornélie was eventually won over by Eugène’s steadfast qualities and his unwavering love for her daughter.)

However there was still something missing from their marriage. Morisot longed for a child. But she was not always in the best of health; she suffered with food intolerances and was often underweight. It was not until November 14th, 1878, four years after her marriage, that Morisot gave birth to Julie at the age of 37. Morisot was instantly in love.

Julie’s birth, even more than Berthe’s marriage to Eugène, established Berthe and Julie irrevocably at the heart of the Manet family and the Impressionist movement. Just as Berthe had modeled for Édouard Manet, so now did Julie.

Renoir, Child with Cat (Julie Manet), 1887. © Wikimedia Commons

Of course Morisot painted Julie interminably. She was obsessed with every detail of her, and there is no doubt she was a pretty child with haunting eyes. Morisot produced some 150 paintings of Julie, but Renoir and Degas were not oblivious to her charms and both painted Julie too. (Renoir’s “Child with Cat” is probably the most famous, and now hangs in the Musée d’Orsay.)

As soon as Julie was old enough to hold a paintbrush, Morisot began teaching her to paint. It was also a way of constantly being with Julie while she worked. Both Morisot and Eugène schooled Julie, but she was also introduced to museums and galleries from an early age in various European countries. Morisot could not bear to be parted from her.

But life is rarely idyllic, and Eugène began to sicken. His cough worsened to such an extent that he was confined to bed, an invalid. He died on April 13th, 1892. Julie was 14 years old and her mother was bereft. Three years later, Julie was an orphan. Morisot had been struck down by a cold that had rapidly turned into pneumonia, and fragile as she was, Morisot had been unable to recover. Morisot, aware that her life was ebbing away, wrote Julie a last letter the day before she died.

“My little Julie, I love you as I die; I will love you when I’m dead; please don’t cry; this separation was inevitable; I would have liked to survive till your wedding…Work and be as good as you have always been; you haven’t made me sad once in your little life. You have beauty and wealth; use them well. I think it would be best if you were to live with your cousins, rue de Villejust, but I prescribe nothing. Give some souvenir of me to Aunt Edma and to your cousins; to your cousin Gabriel, Monet’s Boats Under Repair. Tell M Degas that if he founds a museum he should pick a Manet. A souvenir to Monet, a Renoir, a drawing of mine to Bartholomé. Give something to the two concierges. Don’t cry; I love you even more than I can say; Jeannie take care of Julie.”

Jeannie and Paule Gobillard were the daughters of her older sister, Yves, who were also orphans, Yves having suffered an agonizing death of mouth cancer with Morisot by her side.

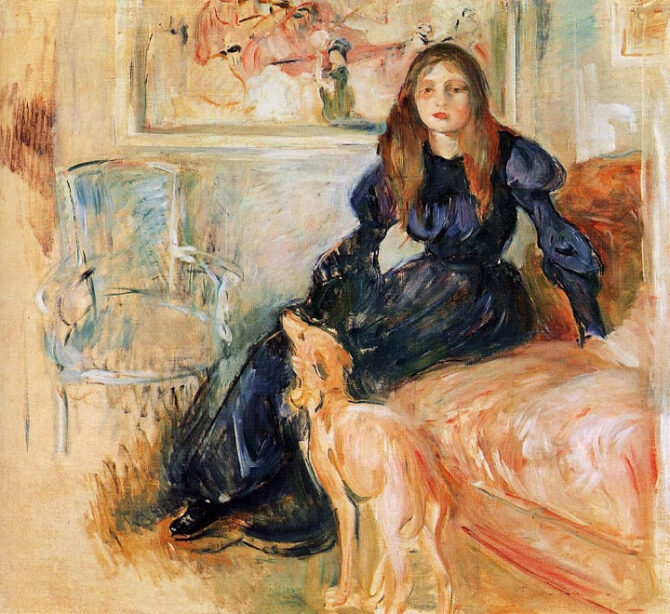

Three years before her death, Morisot had begun holding a weekly salon at her home in Rue Weber near the Bois de Boulogne. (As a now single woman, it would have been inappropriate for Morisot to visit other male artists in their homes or studios.) And it was here where she invited Degas, Monet, Manet and Renoir and Manet’s friend, the poet Stéphane Mallarmé. Mallarmé and Morisot grew close and when Eugène died he gave Julie a pet greyhound named Laertes. On Morisot’s request, Mallarmé became Julie’s guardian on Morisot’s death.

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Portrait de Julie Manet © Wikimedia Commons

The ties between this group of Impressionists and poets who had surrounded Julie most of her life, were as strong as any family bond, and Julie’s welfare after Morisot’s untimely death was paramount. Paul Valéry, the poet and Mallarmé’s protege, proposed to Jeannie, and Degas who was a close friend of Henri Rouart, arranged a meeting in the Louvre between Julie and Rouart’s son, Ernest. Julie was 19 old and encouraged by Degas, agreed to marry Ernest Rouart. As if further proof was needed of the cousin’s devotion to each other, Jeannie and Julie married Valerie and Rouart in a double wedding ceremony five months later. The brides wore identical gowns and the grooms identical jackets. They were not to be separated by marriage either. Julie and Ernest occupied the fourth floor of the apartment building where Julie had spent her life with her mother at 40, rue de Villejust in Passy. Jeannie and Valery moved into the apartment below.

Ernest Rouart was an accomplished painter and collector himself. (In fact, he was the only protege Degas ever took on.) His father, the industrialist Henri Rouart, owned the world’s largest art collection at the time. Degas had chosen well for Julie. Ernest supported her in promoting both her mother’s paintings and other Impressionists. Between them, they had considerable wealth, and spent a healthy proportion of it buying works at auction. The marriage was a happy one, three children followed, but unlike her mother, Julie gave up painting after her marriage and concentrated on collecting and keeping her mother’s name alive.

Berthe Morisot, Eugene Manet and His Daughter in the Garden, 1883. © Wikimedia Commons

Julie had kept private diaries during her mother’s life. These journals, published for the first time in 1987, contain details of conversations between the artists closest to her mother. The Dreyfus affair, which divided the whole of France, was just as divisive in artistic circles. Degas is exposed as an anti-semite and Pissarro as a libertarian. Julie’s personal thoughts display, somewhat surprisingly, how deeply religious she was. (Both Morisot and her father had been distinctly ambiguous in regarding religion.) Julie’s faith, as her husband’s, remained unshakeable all her life. Ernest Rouart died in 1942 aged 68. Julie survived him by another 24 years, dying in 1966 at the age of 87. Both are buried next to each other in Passy Cemetery.

This exhibition at the Musée Marmottan Monet would have surpassed both mother and daughter’s wildest imagination. It is a celebration of lives well lived in the promotion of French, 19th-century Impressionist Art

Musée Marmottan Monet

2 Rue Louis Boilly, 16th arrondissement

Tel: +33 (0) 1 44 96 50 33

Open from Tuesday to Sunday from 10 am to 6 pm. Open later on Thursday evenings until 9 pm. Full-price ticket costs 13,50 euros.

Lead photo credit : Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet et son Lévrier Laerte, 1893, Musée Marmottan Monet

More in Art, history, Impressionist art, Manet, Monet

REPLY

REPLY