In the Footsteps of Edgar Degas in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Remarkable Art from a Difficult Man

Edgar Degas’ fleeting scenes of 19th-century Paris life were simpatico with the mission of the Impressionist artists, but Degas’ talent in composition and draftsmanship surpassed the other members of the group. Degas was exceptionally skilled in painting, sculpture, drawing and pastel. He taught himself photography and was a collector of contemporary art.

Degas was a keen observer of humanity and a master of drawing the human figure in motion. “Observer” is the operative word to describe Degas. Degas was frequently on the outside looking in. The blunt, peeking-through-the-keyhole perspective of his art gave him the reputation as a voyeur. Tagged for posterity as a misogynist, he went to great lengths to paint women in demeaning poses and situations. A life-long bachelor, Degas had no romantic attachments. He drove away his Impressionist colleagues with his irascible attitude and his anti-semitism.

In 1834 Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas was born at 8 rue Saint-Georges (9th arrondissement) in Paris. He contracted his surname himself to seem less posh. There is no ‘day’ in Degas. The son of a wealthy banker – it seems many of the Impressionists had wealthy fathers – he registered to be a copyist at the Louvre in 1853, the instant he finished his formal education. He entered the École des Beaux-Arts in 1855, but after one semester he dropped out. After leaving art school, Degas moved to Italy from 1856 -1859.

Edgar Degas, The Cotton Exchange. (C) Public Domain

On his return, Degas lived at 13 rue Victor Massé (9th arrondissement). Degas developed into a skilled portraitist, depicting himself and family members. He remained at this address until 1870, when he was compelled to serve in the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War. In 1872 he traveled to New Orleans to assist his brother René with the family’s cotton business. Degas painted The Cotton Exchange during his time there. As a result of the American Civil War and the Paris Commune, René Degas’s cotton import-export business failed. The dependable Degas made himself responsible for his brother’s debts. However, it was a challenge that crippled the artist’s finances and he had to relinquish his spacious apartment and move to a smaller Montmartre studio.

Sales from Degas’ many ballet scenes were intended to bail out the family company. On the canvas, Degas’ lithe, young dancers were like a bouquet of pastel tutus. But in reality Degas’ dancers were not romantic figures at all, but underfed and underage girls hiding the aches and pains of a grueling regimen. Hopes for their stellar careers were pinned on rich stage door Johnnies, who, for the subscription of a few performances, were allowed to prey upon these teenaged girls for sexual favors. Degas depicted over 1500 works centered on the ballet. Some images like L’Etoile of 1877 show the glamour, others, like The Dance Lesson, 1879 show the pain.

Edgar Degas, The Dance Lesson. (C) Public Domain

Manet introduced Degas to the style that would be coined Impressionism. Less spontaneous than the other Impressionists, Degas had no interest in the plein-air study of nature, turning instead to the urban life of theaters, circuses, and cafés for his inspiration. Degas captured people absorbed in the gestures of their occupations. These included washer women, café singers, milliners, and scenes that hinted at the seamy side of Paris – brothels, prostitutes, and drunken demimondaines. After 1874 Degas no longer exhibited at the respected Paris Salon preferring instead to exhibit with Society of Independent Artists, aka the Impressionists, and was a major hand in organizing several of the Impressionist exhibitions.

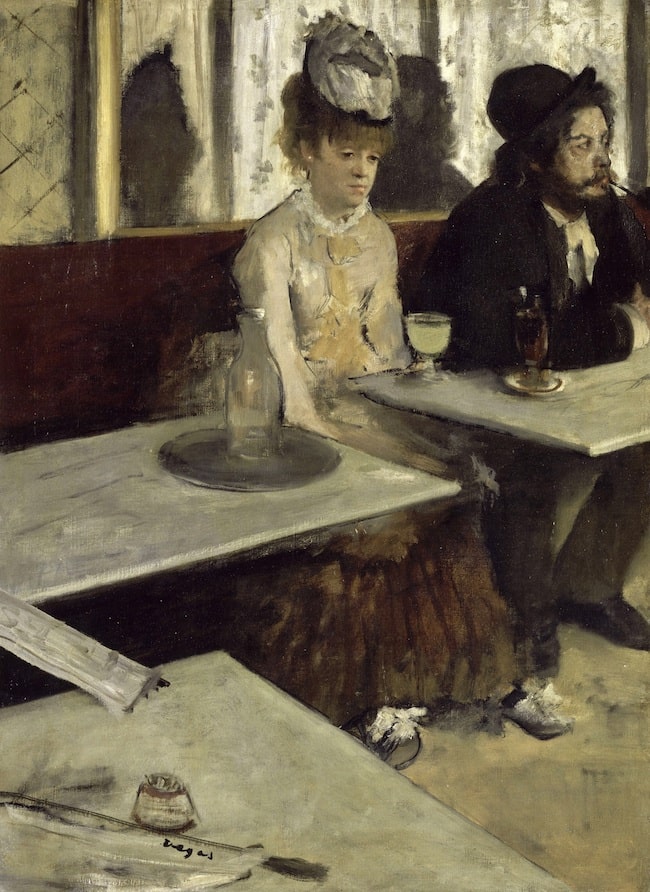

Edgar Degas, L’Absinthe. (1875–1876). Public Domain

From 1872/73 -76 Degas lived at 77 rue Blanche (9th arrondissement). Following this, Degas lived for a year at an amazing apartment at 4 rue Frochot (9th arrondissement) which boasted a glass roof and a photographers’ studio. From this address he painted the drunken and bored Absinthe Drinker in 1876.

At this time, Degas’ eyesight began to suffer. He worked increasingly in pastel which didn’t demand such acute eyesight. He used a professional draftsman to help him with the perspective of Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando. The Cirque Fernando opened in 1875 much to the delight of the Belle Époque artists of Montmartre. Degas, as well as Renoir, Seurat, and Toulouse-Lautrec, were part of the audience.

Edgar Degas, The acrobat Miss La La. (C) Public Domain

From 1877-79 Degas lived at 50 rue Lepic (18th arrondissement). By the 4th Impressionist Exhibition in 1879 Degas was living at 19 Pierre Fontaine (9th arrondissement) and would do so until 1882.

Although he participated in all but one of the eight independent exhibitions between 1874 and 1886, Degas’ realism didn’t fit easily into the Impressionist mold. During his tenure with the Impressionists he frequently angered other members, especially Caillebotte. Wanting to define a coherent style for the society, Caillebotte blamed Degas for attempting to pack the group with lesser-known artists whose work tended toward the realistic. Caillebotte accused Degas of “spreading disunity into our midst.” Cezanne, Morisot, Renoir and Sisley were still stinging from the discord Degas had sown and would not participate in the 4th exhibition.

The somewhat complicated title of the 1879 exposition, ‘The 4th Exhibition Made by a Group of Independent, Realist and Impressionist Artists”, was a form of compromise between Caillebotte and Degas, placating Degas by tucking in the word realist where it suited him.

Edgar Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen. (C) Public Domain

Degas was resolute that no member of their group should exhibit at the established Paris Salon. He was furious with Pissarro for congratulating Renoir and Monet for their successes there, which, in Degas’ eyes, showed disloyalty to the Impressionist cause. Again, Caillebotte intervened and mended the bond between them. In 1881 Degas created the controversial Little Dancer of Fourteen Years. Shown at the 6th Exhibition, the bronze statue with her cloth accoutrements further demonstrated Degas’ interest in dance and corruptibility. Caillebotte restated that Degas’ realistic tendencies were dividing the group.

From 1882 to approximately 1888 Degas resided at 21 rue Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (9th arrondissement). During the 1880s Edgar Degas embarked on a series of pastels of women – mainly red-haired – seemingly captured candidly in their living quarters. Although faithfully rendered, his subjects were criticized for their ungainly poses and today these images are questioned for Degas’ objectification of woman. These works which included women bathing privately in shallow tubs or drying themselves in uncomfortable poses serve to demonstrate why current thought considers Degas as a voyeur.

The Tub 1886 is an example of this keyhole voyeurism, in which the model, with a table encroaching on her space, squats awkwardly in a zinc bath. These models lack a human touch – none turn to face him despite the fact that Degas was obviously with his subjects for hours at a time in intimate, limited spaces. Degas remained a bachelor. He had a few close female friends but no known romantic entanglements. This lack of female contact may have been the reason Degas preferred to stage his models as if they were being leered at. One woman who posed for Degas reported that, “He’s a strange gentleman – he spends the whole four hours of the sitting combing my hair.” He showed this suite of pastel nudes the 1886 Eighth and final Impressionist Exhibition after which Degas rarely showed his works.

According to Theo Van Gogh’s address book, after traveling to Geneva, Naples, Spain and Morocco, Degas settled at 23 rue Ballu (then 18 rue de Boulogne) from 1888-1890 where he would continue to depict women at their bath.

In 1890 Degas moved back Rue Victor-Massé, this time at number 37 where artist Suzanne Valadon would visit him daily. The one-time favorite model of Renoir and Puvis de Chavannes, Valadon impressed Degas with her early attempts at art. Degas was her first buyer, buying a chalk drawing on the first day they met. To Valadon, Degas was an affectionate and generous friend. She became his pupil – an accepted part of his household – working in a cultivated atmosphere. Degas introduced her to various art dealers and hung her works next to those of Ingres and Delacroix. As Degas slowly began to withdraw from the public eye, he became a more aggressive art collector. He purchased work by contemporaries such as Pissarro, van Gogh, Manet, Gauguin and Cézanne. Degas also respected and encouraged the talents of Mary Cassatt.

Edgar Degas, Place de la Concorde. (C) Public Domain

The new medium of photography interested Degas. Historically many of Degas’ paintings are oddly framed or cropped like snapshots. The Place de la Concorde, showing the Viscount Lepic and his daughters, is an example of this type of framing. In the 1890s when amateur photography was in full-swing, Degas began taking photos with a passion. During 1895-96 Degas made about 60 prints but only a fraction of Degas’ photographs are known.

Degas became increasingly reclusive. Degas’ loneliness and looming blindness did nothing to temper his sardonic wit. He ridiculed his life-long painter friends. Degas mocked Renoir’s style, calling it as puffy as cotton wool. He also likened Renoir at his easel to a cat playing with multi-colored balls of wool. Degas described the famed Symbolist Gustave Moreau as “a hermit who knows what time the trains leave,” and unkindly compared Puvis de Chavannes to the condor in the Jardin des Plantes.

One of the most damning features in Degas’ personal life was his stance regarding the Dreyfus Affair. The scandal originating from the wrongful treason conviction of Alfred Dreyfus, an artillery officer of Jewish descent, divided France from 1894 to 1906. The vehemently anti-semitic Degas fell into the pro-Army, anti-Dreyfusard camp where Renoir and Cezanne unfortunately kept him company. Others, like Monet, Pissarro, and Mary Cassatt, were convinced of Dreyfus’ innocence.

The artist’s virulent and inexcusable anti-semitism may have stemmed from the failure of De Gas’ family’s cotton and banking enterprises. Degas blamed his misfortunes on Jewish bankers, conveniently scapegoating big names such as the Rothschilds.

The saddest consequence of Degas’ anti-Dreyfus stance was his break with Ludovic Halévy, his dearest friend for the previous 40 years.

Degas struggled throughout the last years of his life. Without aim, the almost blind artist wandered through the Paris streets. He stopped producing art in 1912. The demolition of his apartment in the same year forced him to move to 6 Boulevard Clichy (18th arrondissement) where he lived an almost hermetic life with his housekeeper Zoe. When the curmudgeonly Degas died at age 83 he left behind some 2,000 paintings and 150 sculptures.

Lead photo credit : Edgar Degas. (C) Public Domain

More in artists, gallery, Impressionist art, Manet, Monet, paint