Frida in Paris: The Clothes, The Exhibition, The Affair

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

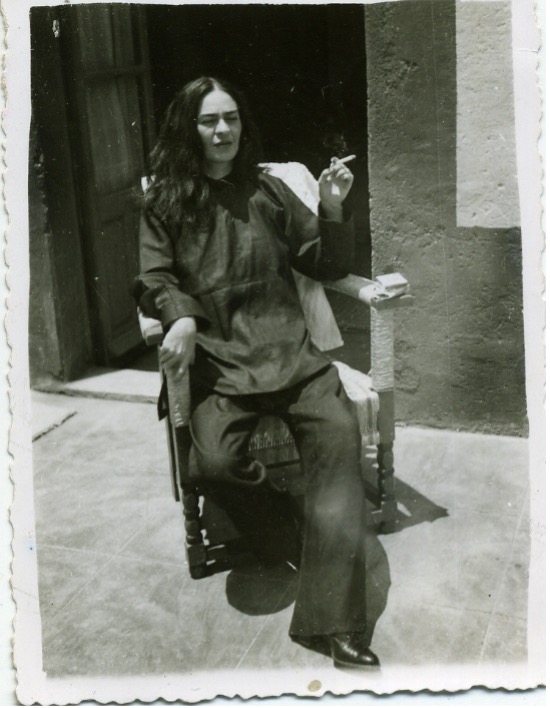

Frida Kahlo, the Mexican artist whose life and art command an iconic status few other women can claim, may need no introduction in 2023. Her extraordinary biography inspired Salma Hayek’s film Frida (2002). Her unique face and fashion statements grace countless covers of books, posters, mugs, and kitschy incarnations. For most of her professional career, she was considered an “artist’s wife” who dabbled in her own studio. Today, she is one of Mexico’s best known national treasures, especially in Paris, where her sold-out exhibition at the Palais Galliera more than makes up for her 1939 Parisian disappointments. However, the theme of this much-anticipated solo show is not her heart-wrenching self-portraits that most of her fans admire. Instead, this show focuses on her carefully curated image that blended her nationalistic pride with the need for cosmetic disguises.

Frida Kahlo by Toni Frissell, US Vogue 1937. © Toni Frissell, Vogue / Condé Nast

Frida Kahlo: Au-Delà des Apparences (Beyond Appearances) at the Palais Galliera, the Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris, marks the 84th anniversary of Frida’s one and only trip to Paris from January 21 – March 24, 1939. Composed of over 200 objects, this extraordinary display of Frida’s clothes, jewelry, make up, corsets, shoes, and one prosthetic, surrounded by photos, paintings, and photographs, maps the intersection between her private and public personas. “Beyond Appearances” means that here we will learn more about Frida than her numerous confessional self-portraits seem to convey.

Bottines customisées en satin. Customised silk ankle boots. © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

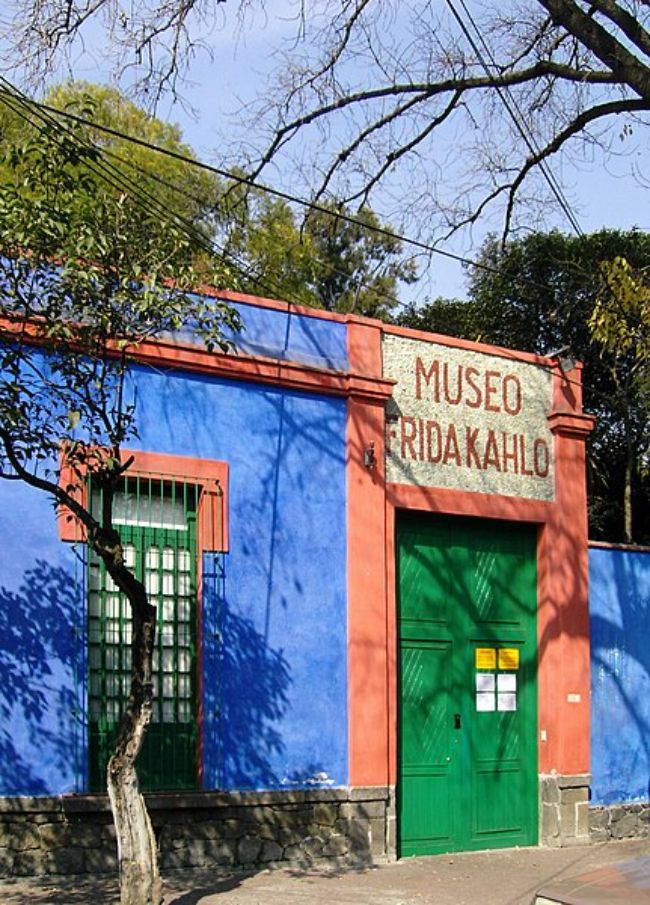

Unfortunately, this magnificent Frida Kahlo exhibition, which opened on September 15, 2022 and closes on March 5, 2023, sold out well in advance of its finale. Therefore, this review tries to offer a bit of consolation through the numerous photos and links to the video tours in English and in French. In addition, I highly recommend the catalogues, in French and English, which provide rich educational commentaries about the history of modern art in Mexico, Frida’s life, and her possessions. Through these virtual opportunities, you learn about the curators’ perspectives which shape this particular approach to an alternative Frida Kahlo-lore. I also recommend Frida Kahlo: Her Universe, published by the Frida Kahlo Museum in 2022. The photos, essays, and insights seamlessly intertwine the art and archives Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera left behind in their Casa Azul (The Blue House), now the Frida Kahlo Museum, opened to the public in 1958.

The Frida Kahlo Museum (La Casa Azul), Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico

La Casa Azul (The Blue House) is located in the Colonia de Carmen neighborhood of Coyoacán, in Mexico City. Built in 1904 by Frida’s parents Matilde Calderón y González, of both Spanish and indigenous heritage from Oaxaca, and Guillermo (originally Carlo Wilhelm) Kahlo, a German immigrant, who became a successful commercial photographer, it was where Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón was born on July 6, 1907 and died on July 13, 1954.

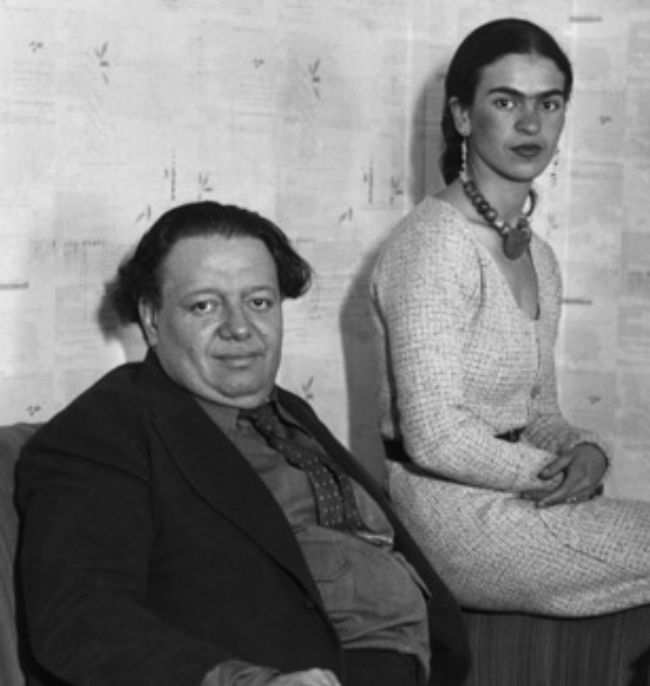

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, undated. Wikimedia commons.

Immediately after her death, her husband, Diego Rivera, the titanic Mexican muralist, sealed away Frida’s personal possessions in her bedroom. Rivera then made arrangements in his will to donate their house to the Bank of Mexico with the stipulation that it would become a museum after his death, which occurred on November 24, 1957. From 2003 to 2007, curators and conservators organized and classified thousands of objects stored away in trunks and wardrobes. The research from these three years of meticulous study form the basis for the Paris exhibition and its previous incarnations in 2012 at La Casa Azul, in 2019 and 2020-21 as Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, in Brooklyn and in San Francisco, respectively.

Frida Kahlo revealing her corset painted under her huipil by Florence Arquin, ca. 1951. © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo archives, Bank of México, fiduciary in the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera Museums Trust

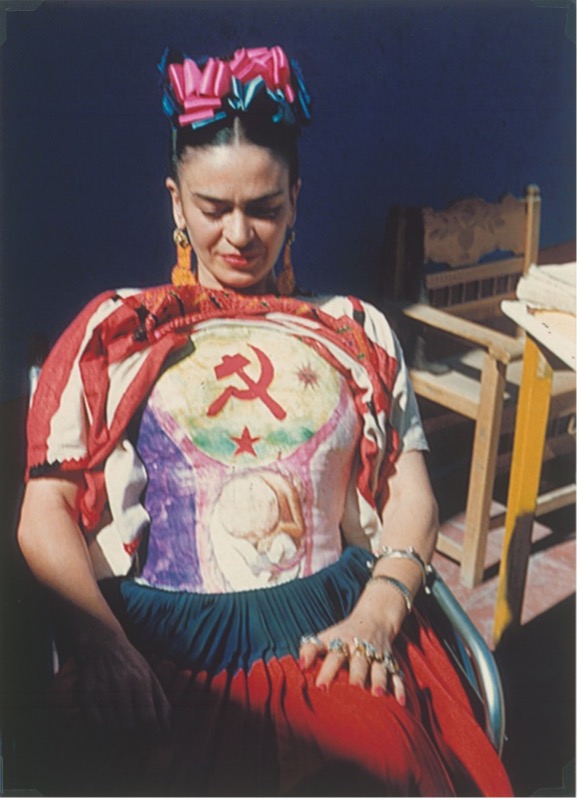

In all of these endeavors, the core concept highlights the artist’s sartorial decisions which reflect her fervent identification with her beloved Mexico, both its traditional and modernist cultures, the latter inspired by the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Woven into this individualized image as a modernist Mexicana were her practical considerations. Her custom-made shoes balanced her feet, since one leg grew longer than the other after she contracted polio at age six. Her long skirts and blouses covered her plaster casts and corsets, which braced her injured spine caused by a grave bus accident on September 17, 1925, when she was 18. (Almost her whole body was crushed and her pelvis area was impaled by one of the bus’ railings.) The bus crash occurred while Frida was studying at the National Preparatory School, where she had watched Diego Rivera paint his famous mural Creation in 1922-23. Months of convalescing in her bed redirected her ambitions from medical illustration to inventing an imagery that viscerally described her pain. In photos, we can see her at work at a specially installed easel using a mirror placed above her head to copy her likeness. Her signature self-portraits grew out of her incessant discomfort and the fact she became her most conveniently located model. From this moment until the end of her life, Frida underwent dozens of surgeries related to the injuries sustained in this crash, including the amputation of her lower right leg in 1953.

Plaster corset painted by Frida Kahlo © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Fashion historian Circe Henestrosa (who helped curate this show and others) wrote poignantly in her catalogue essay: “Placing disability at the forefront of my interpretation of Kahlo’s personal style provokes questions about disability as part of human experience, its relationship to fashion, dress, femininity and identity. It was through her self-portraits and the adoption of traditional Mexican dress that Kahlo was able to examine her life, her political views, her health struggles, her accident, her turbulent marriage, and her inability to have children. When Kahlo’s wardrobe was discovered, I felt I had met her personally for the first time, understanding her through her unique wardrobe, and viewing her through the lenses of disability, ethnicity, fashion, and dress.” (From “Appearances Can Be Deceiving—Frida Kahlo’s Construction of Identity: Disability, Ethnicity and Dress,” in Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up, The Victoria and Albert Museum, June 16 – November 18, 2018.)

Frida Kahlo by Antonio Kahlo, 1946. © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo archives, Bank of México, fiduciary in the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera Museums Trust

Frida’s various physical challenges and her determination to sort out her multiethnic identity in a post-Porfirio Díaz Mexico produced a visual language that her peers and art historians have labelled “surrealist.” Frida vehemently disagreed. Surrealism grew out of the unconscious, the dream, inspired by Sigmund Freud’s book The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). Frida knew this and said: “They thought I was a Surrealist. I wasn’t. I painted my own reality.” Although she achieved some recognition during her short lifetime (she died at 47), her international stardom did not explode until well after her death, thanks to several feminist art historians, most notably Hayden Herrera and her groundbreaking 1983 biography.

Prosthetic leg with leather boot ans appliqued silk with embroidered Chinese motifs. © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

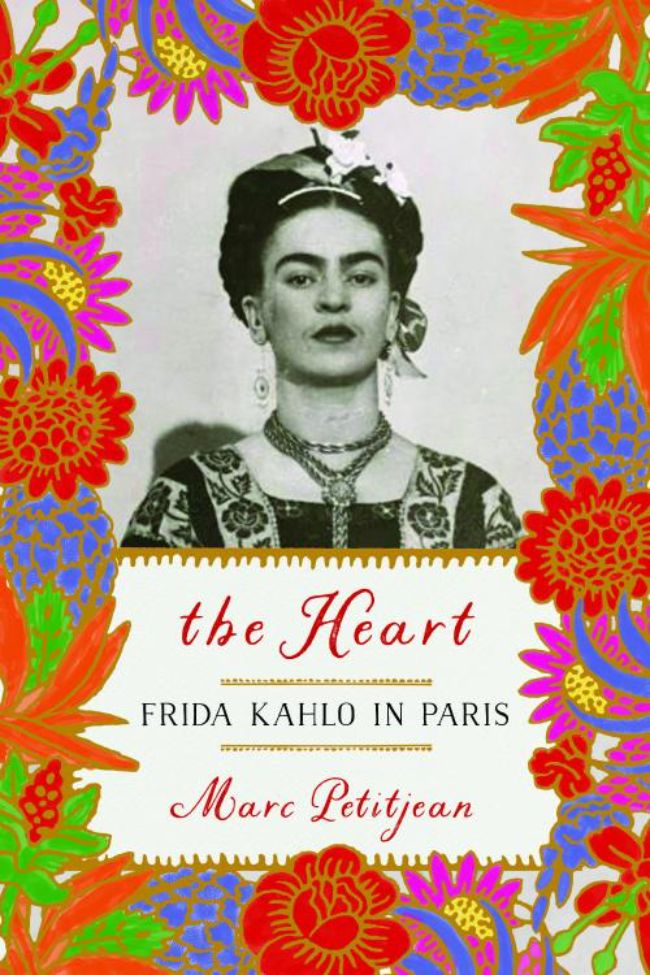

Marc Petitjean, “The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris,” translated by Adriana Hunter (The Other Press, 2020)

Marc Petitjean’s Le Cour: Frida Kahlo à Paris, published in 2018 and translated into English as The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris by Adriana Hunter in 2020, refers to the one painting Frida gave her Parisian lover Michel Petitjean in 1939. Written by Michel’s son Marc, it chronicles Frida’s experiences and impressions of her visit, including her candid critiques of her host André Breton and others within his artistic circles. She had made the trip with two goals in mind: to install her solo exhibition which Breton promised her when he and his wife Jacqueline Lamba stayed with Frida and Diego in their home in 1938, and to raise funds for the Republicans still engaged in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). To her great displeasure, neither came to pass.

Frida Kahlo by Dora Maar, 1934. © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo archives, Bank of México, fiduciary in the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera Museums Trust / ADAGP, Paris 2022

Frida set sail for France from New York sometime in mid-January and arrived in Le Havre on the SS Paris on January 21, 1939. She then took a train to Paris where she was met by Jacqueline Lamba and her close friend Dora Maar, the photographer and Picasso’s current paramour. From that moment to her departure on the SS Normandie, Frida managed to power through a wide range of challenging situations, beginning with the cramped and cluttered accommodations in the Jacqueline Lamba and André Breton apartment (their 4-year-old child’s room), then suffering an acute bacterial infection in her kidneys that sent her to the American Hospital, and, above all, suffering the “insult” of Breton’s failure to dedicate a solo exhibition to her work- instead shoehorned into a clumsy notion of Mexico’s surrealistic culture.

Frida Kahlo and Jacqueline Lamba, Pátzcuaro Mexico 1938, unknown photographer, featured in The Militan Muse, 1938 – Thames and Hudson website

André Breton and Jacqueline Lamba spent mid-April through the end of July in Mexico living at the Riveras’ home in a spacious room just off of their colorful tropical garden. Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova were already installed as houseguests since December 1936. In 1937, Frida and Trotsky had an affair. In May 1939, several weeks after Frida returned from Paris, Trotsky and Diego Rivera decided to parts ways after an argument. For Breton, Trotsky’s proximity during his visit corresponded perfectly with his desire to write a revolutionary manifesto about Marxism. Once in Paris, Frida felt the Bretons’ reciprocal arrangements for her were woefully inadequate. By the end of January, Frida moved into the Hotel Regina within walking distance to the Louvre, one of the few places in Paris that Frida thoroughly enjoyed.

Rebozo and cotton huipil, silk skirt with woven velvet floral motifs. © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

At the Hotel Regina she continued her amorous relationship with Jacqueline Lamba. Meanwhile, she wrote letters to her lover in New York, Nicolas Muray, wherein she complained about the Bretons’ accommodations, André Breton (the so-called “pope of Surrealism”), and the whole Surrealist entourage: “There is something so false and unreal about them that they drive me nuts.” (Herrera, page 246). She also bemoaned the fact in early February that the paintings she sent to Paris were still in the custom house and no gallery space for her exhibition had been secured. Then she developed a painful kidney infection.

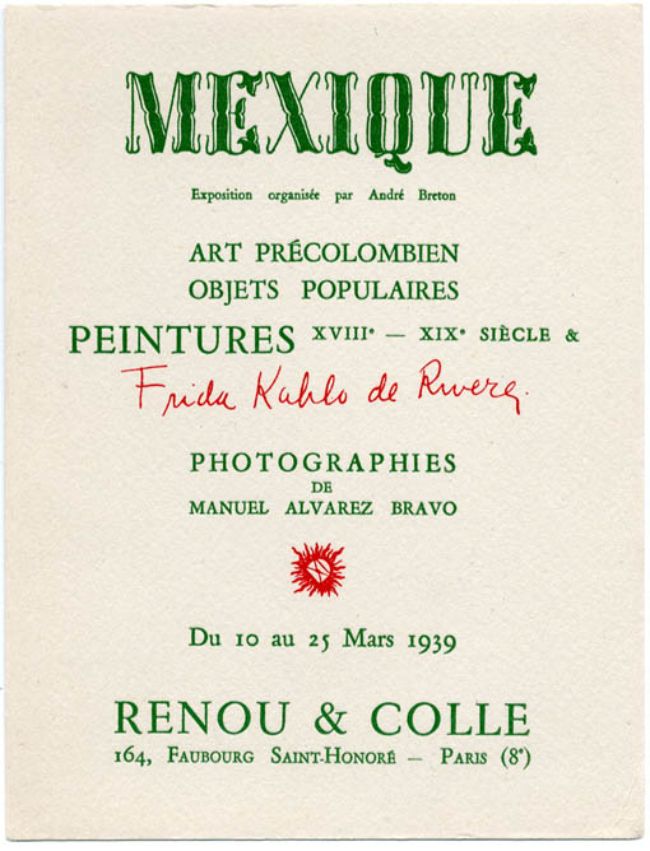

Poster for André Breton’s exhibition Mexique at Renou and Colle

Fortunately, Marcel Duchamp’s American partner Mary Reynolds brought Frida home from the hospital and gave her a place to convalesce. There, on their own, Frida and her new French lover Michel Petitjean, whom she met through Pierre Colle, enjoyed privacy and the deepening of their feelings for each other. Colle and his partner Renou finally agreed to take on Breton’s Mexique exhibition, which Michel Petitjean organized under Breton’s direction. (This is how Frida met Michel.) A bit of a hodge-podge that featured Pre-Columbian objects, Mexican folk art from Breton’s collection, photographs by Manuel Alvarez Bravo, 18th and 19th century paintings, and Frida’s 18 paintings felt like an insult to this proud Mexicana, who found Breton’s characterization of Mexico as “surrealist” completely ridiculous. In Frida’s opinion, the Breton’s collection was merely “junk.” Nevertheless, the opening attracted numerous art luminaries. Wassily Kandinsky, Juan Miró, and Picasso attended. Picasso gave her a pair of earrings made of tortoise-shell shaped into hands with gold cuffs, and he also taught her the Spanish song “El Huérfano” (“The Orphan”).

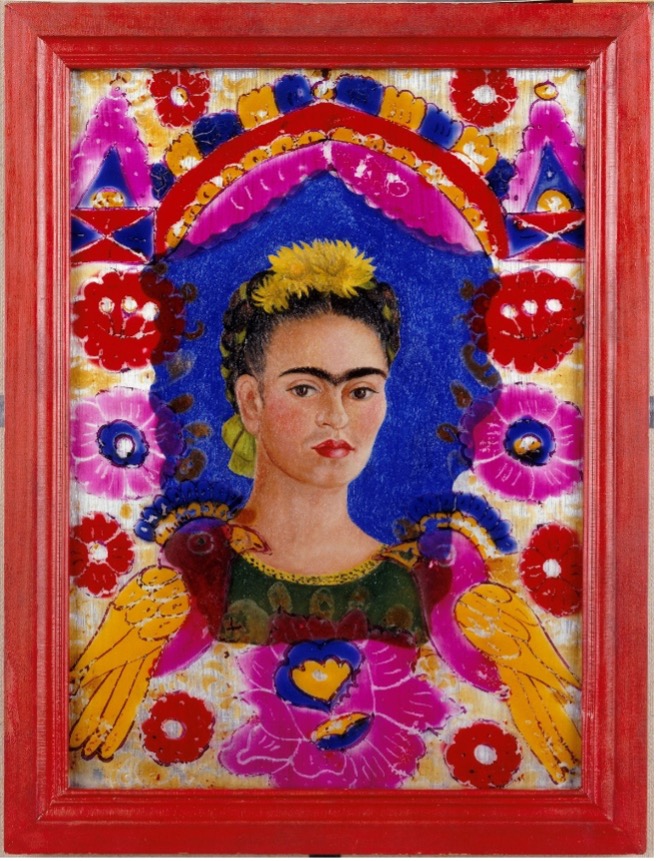

Best of all, Frida sold one work The Frame (1938) to the Louvre, becoming the first Mexican artwork acquired by the French government. Today, it belongs to the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou and is among the few works of art featured in the Palais Galliera exhibition.

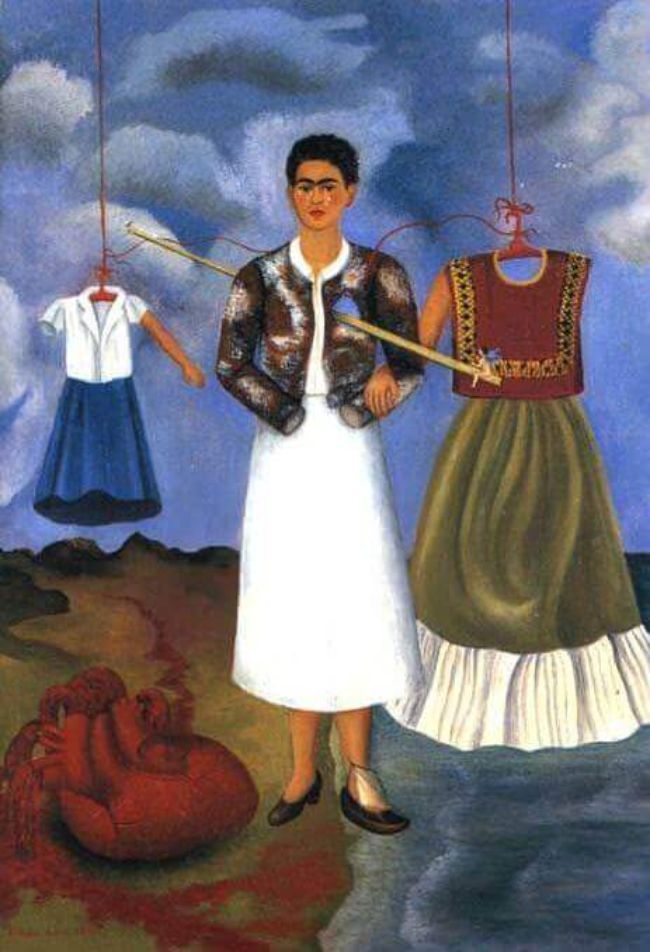

Frida Kahlo, Memory or The Heart, 1937, Private Collection

As Frida prepared to leave Paris, she gave Michel Petitjean her painting The Heart, which Marc Petitjean did not know came from this affair until he met someone who suggested he read father’s letters. In his book, the author explains the painting:

In The Heart she alludes to three periods of her life: on the left-hand side of the painting hang the schoolgirl’s white blouse and blue skirt that she wore when she met Diego. The central figure of Frida, with her short hair and modern clothes, represents her as an adult at the time when she realizes that Diego is cheating on her with [her sister] Cristina. On the right is the Tehuana costume that characterizes the wife emotionally attached to her Mexican identity. The ripped-out heart lying bleeding on the ground expresses her pain. The boat is a reference to the orthopedic shoe she had worn since contracting polio as a child; the metal rod represents a rail that impaled her during a trolley car accident. The painting can, however, also be read as a form of forgiveness, because the Frida of the Mexican costume—which Diego so liked—is arm in arm with the angry Europeanized Frida.

The Heart brings together elements of the major events in the artist’s life: her childhood polio, her terrible accident, and Diego’s chronic unfaithfulness.

In 1939, Frida’s choice of traditional Mexican clothes cut an exotic figure in the middle of this fashion capital. Haute couture designer Elsa Schiaparelli was so impressed, she created a dress inspired by “Madame Rivera.” This gesture suited Frida perfectly. For Frida came to conquer Paris, rather than the other way around.

Cotton huipil with embroidery, printed cotton skirt with embroidery and ruffle. © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

The proud attitude Frida brought to Paris in 1939 may shed light on Beyond Appearances. Frida did not consider Paris her cultural mecca for artistic inspiration, like so many other people from abroad. Her husband Diego Rivera spent 15 years in Europe, mainly in Paris from 1907 to 1920, honing his Cubist vocabulary. When Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921, he shed most of this Cubist style to create a new modernist Mexico aesthetic. To this end, he first investigated indigenous Mexican artworks and crafts, wresting from these sources a visual language for his powerfully distinctive murals. As a couple, the Riveras joined forces with other Mexican artists and literary figures to create a unique aesthetic for this new Mexico which would emphasize the empowering of the Mexican people over colonialism. In the beautifully designed and installed Palais Galliera exhibition, we become immersed in Frida’s determination to express this distinctly Mexican identity through her choice of clothes, jewelry, and coiffures.

Guatemalan cotton coat, Mazatec huipil hand-embroidered and satin ribbons © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Circe Henestrosa’s scholarship emphasizes the integration of her Mexican identity and the disguising of her disabilities, such as her plaster corsets and custom-made shoes. In her contribution to the exhibition, Henestrosa hopes to instill an appreciation of Frida’s ability to cope and to thrive by virtue of her resourcefulness and her resilience. In a different, complementary vein, Oriana Baddely wrote in her catalogue essay “Frida Redressed” about the iconography of Frida’s distinctive clothing, which she often made herself. Here we learn about the women from Isthmus of Tehuantepec whose matriarchal society signified empowerment and resistance during the colonial period that ended in 1810. By choosing recognizable Tehuana styles, Frida “represented the indigenous woman resisting conquest and colonization.” Thus, Baddeley claims “she finds strength by adopting clothing with references to redemption and hope even while she is presenting her body as injured, not only in her own personal reality, but also through the metaphorical pain and struggle of Mexico’s past.” This carefully considered symbolism for her clothes also applied to her jewelry made of authentic Pre-Columbian stones and to contemporary silver creations.

Hand-embroidered in black thread, semi-synthetic full length skirt © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Bracelet of silver and amethyst, 1940s © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Necklace of irregular pre-columbian jade beads assembled by Frida Kahlo © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Frida Kahlo Necklace in carved obsidian and red cotton thread, assembled by Frida Kahlo © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

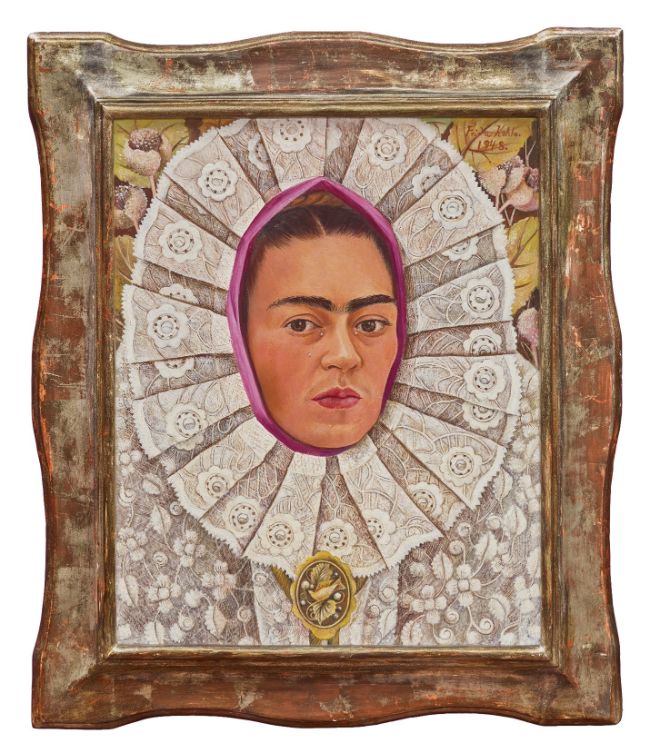

Self-portrait with a Resplandor, Frida Kahlo, 1948 © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo archives, Bank of México, fiduciary in the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera Museums Trust

Ensemble Comme des Garçons, Printemps-Été 2012, collection “White Drama.” Collection du Palais Galliera, Paris. © Courtesy of Comme des Garçons, SS 2012 / JeanFrançois Jos

The Palais Galliera website also includes photos of their ancillary exhibition of clothes and accessories inspired by Frida Kahlo’s clothes and corsets, such as Comme Les Garçon’s interpretation of the resplandor, a “radiance,” which is a lace Tehuana huipil worn as a headdress framing the face and covering the sleeves. Through this section of the show, Frida posthumously achieves her most delicious revenge.

One wonders if she would approve of this belated “comeback.” I hope so. At least it projects her honestly and provides insight into her so-called “reality,” which she tried to convey through the iconography of her self-portraits, whether clothed or nude. Fortunately, this time in Paris, Frida managed to exert her personality “beyond appearances” (beyond her Madame Rivera status) so that we might discover the woman and the artist she truly was.

Bottle for Chanel n°5 lotion. © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Compact and powderpuff with blusher © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Nail varnishes, before 1954. © Museo Frida Kahlo – Casa Azul collection – Javier Hinojosa, 2017

Lead photo credit : The Frame, Frida Kahlo, 1938 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Jean-Claude Planchet © Banco de México D. Rivera F. Kahlo Museums Trust / ADAGP, Paris 2022

More in exhibition, Frida Kahlo, history

REPLY

REPLY