Women Artists Rocking the 1920s and 1930s

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

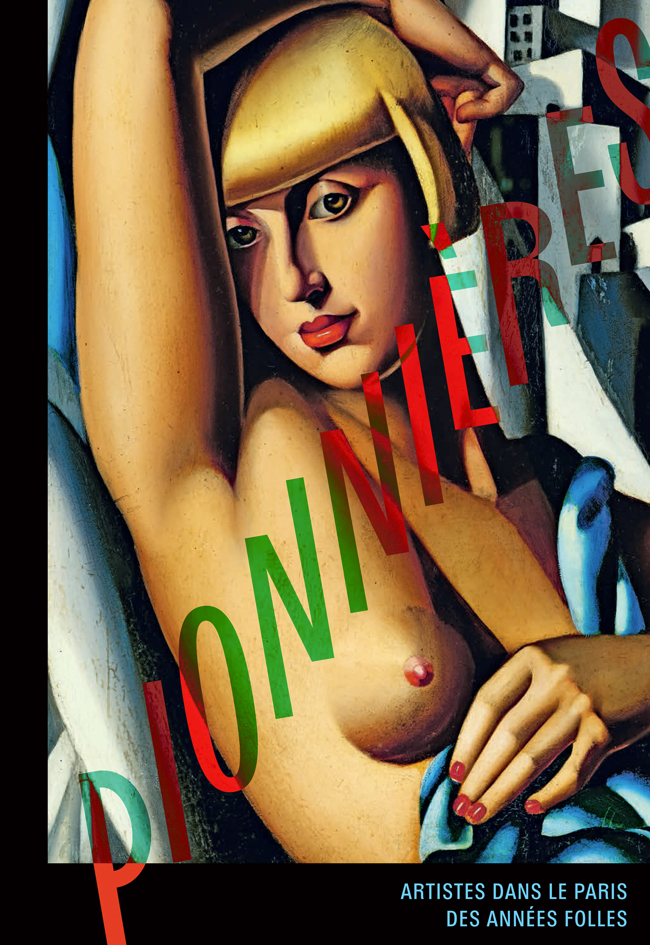

One of the best exhibitions of the Spring 2022 art season in Paris closed on July 10th. It’s tragic because this outstanding curatorial endeavor deserves to stay open throughout the summer, if not longer, so that the maximum number of art fans have an opportunity to see this magnificent, highly-informative show. Pioneers: Women Artists from the Roaring Twenties (Pionnières: Artistes dans le Paris des années folles) at the Musée du Luxembourg is a celebration and revelation. It celebrates the great accomplishments of 45 extremely gifted modernist women artists in various media, and it reveals to us, in nine thematic groups of artworks, a new way of studying the contributions of women to the arts during this particular era.

The whole experience helps us navigate the exhilaration of “les années folles” (the crazy years), referred to in English as “The Roaring Twenties” or “The Jazz Age.” The culture was hot, but the art was cool, controlled, tamed after the outrageous experiments of the Fauves and Cubists during the first 15 years of the 20th century. Art historians call this clean, streamlined “return to order” the new “classicism.” Decorative arts scholars call this period Art Deco, inspired by the French words “art décoratif,” which made a big splash in Paris at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in 1925. However, there were some emerging women artists whose style looked restrained, but their content was not. For them, the party had just begun.

A bit of background: Over half a century ago, the major mover-and-shaker in the history of feminist art history, Linda Nochlin, published “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (ArtNews, January 1971). In this ground-breaking article, Nochlin blamed the paucity of truly strong influential women artists on the lack of opportunities for training, exhibitions, and financial support in the male-dominated art world. The article became a clarion call to action. Female, and some male, art historians took out their research shovels to unearth the history of women artists buried by years of neglect. However, unwittingly, the article embedded a negative element too, because it declared that the art made by women, so far, never measured up to their male counterparts, no matter how “interesting” their efforts might seem. This perspective still demeaned women artists in the eyes of art historians, curators, and collectors. As a result, centuries of women artists were automatically perceived as second-rate by the museums, the galleries, the auction houses, the curriculum, and academia. Consequently, the amount of time and money invested in educating the public about women artists has received short-shrift – and remains so to this day.

To change this criterion completely requires shifting away from the white, European, male-centric canon and toward a new paradigm, a different notion of what constitutes “great” art. Pioneers clearly demonstrates a step in that direction. For here we find art that speaks for a multitude of authentic human experiences that deserves our consideration.

In this regard, Pioneers has “pioneered” a new approach to women artists from the 1920s and 1930s that should increase our knowledge and spark greater interest in the artworks themselves. To that end, chief curator, art historian, heritage curator, and director of AWARE (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions), Camille Morineau, along with associate curator and art historian Lucia Pesapane introduce more complex, accessible analyses of what women brought to the arts and for which women today should be quite proud. This is an exhibition on women by women for everyone.

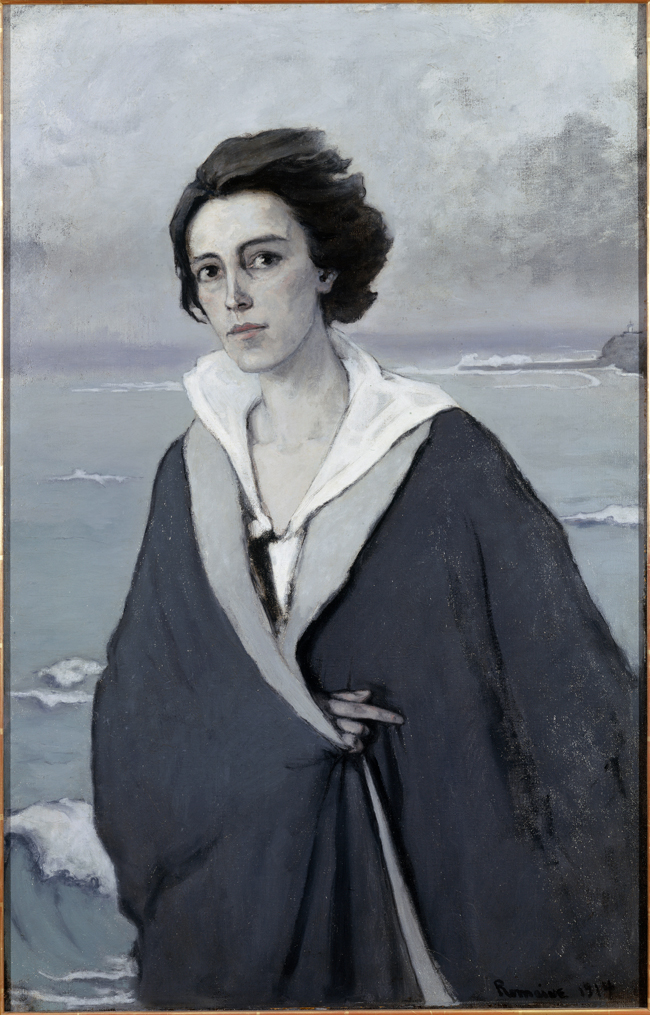

Moreover, the curators’ enlightened scholarly approach chose a positive feminist message. These women artists portray the “new woman,” someone who is independent and self-made. From Aleksandra Belcova’s and Jacqueline Marval’s sportswomen to Tamara de Lempicka’s erotic nudes to Chana Orloff’s majestic Portrait of Romaine Brooks, we witness an era of female confidence. Perhaps, as the curators argue, this self-assurance came from the participate of women in “the Fourth Army” during World War I. These nurses, farm laborers, seamstresses, etc, supported the soldiers at the front by enlisting their skills as civilians in the workplace. We also have the influence of business-minded women, such as the singer-dancer Josephine Baker and the couturier Coco Chanel.

Romaine Brooks, Self-Portrait on the Seashore, 1912, oil on canvas, 105 x 68 cm, Musée franco-américain du château de Blérancourt / dépôt du Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’Art moderne / Centre de création industrielle, Paris © The Romaine Brooks Estate # Pascal Alcan Legrand / photo Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. Rmn-Grand Palais / Gérard Blot

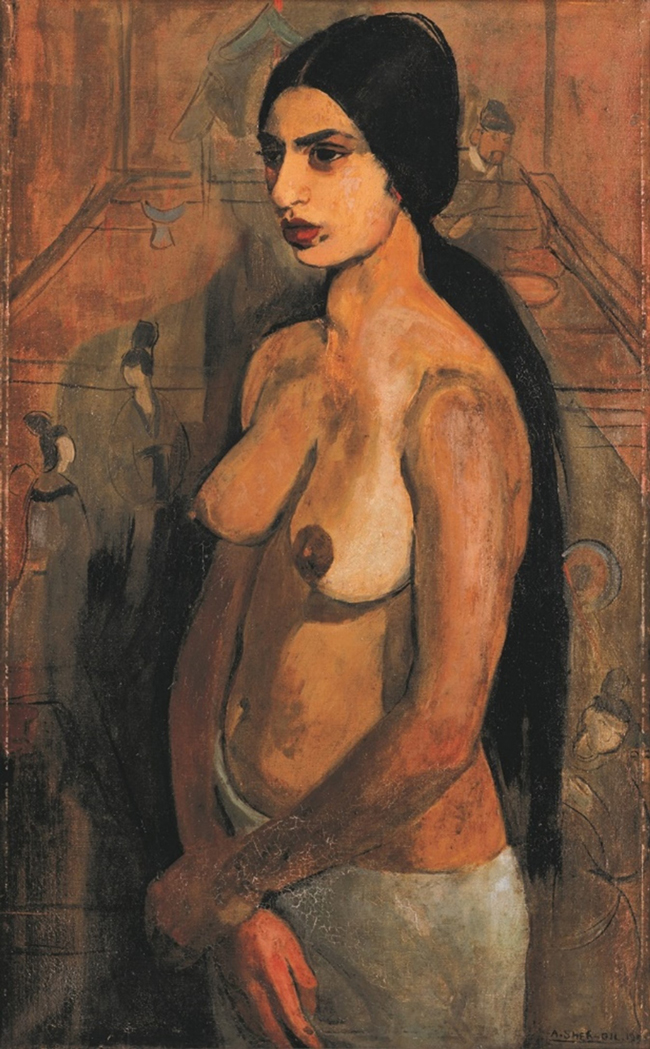

In the exhibition catalogue we read about the personal bravery of numerous women artists who launched their careers from meager beginnings. Many artists in the exhibition came to Paris from other French cities or from abroad, such as the Hungarian-Punjabi Indian painter Amrita Sher-Gil, eager to learn the latest trends in modern art. Foreign artists learned French and found compatriot communities that integrated with other French and international artists’ circles.

Amrita Sher-Gil, Self-Portrait in Tahitian Skirt, 1934, oil on canvas, 90 x 56 cm, New Delhi, Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, © Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

On the subject of gender identity, the gallery called “Les Garçonnes” recalls the radical boyishness of the flapper bob and flat-chested silhoutte without corsets, introduced before World War I by Paul Poiret. In another gallery, the curators help us explore the works by artists who were born one gender and chose to assume another as they reached adulthood, such as French Surrealist photographer and writer Claude Cahun, who identified as neuter. Her performance self-portraits date back to 1912, well before today’s well-known “selfie” photographers Cindy Sherman and the late Francesca Woodman. Cahun belongs to the section called “The Third Gender.” Here, gender-bending sartorial statements cover the walls, such as in the eerie portrait of sculptor Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge by Romaine Brooks, which belongs to the ancillary subject called “The Amazon.” Dedicating this space for references to gender fluidity and homoeroticism in history considers the various lifestyles cultivated by a wide range of social circles during this period.

In the case of a male identifying as a woman, we can study the fanciful portraits of Lili Elbe by Gerda Wegener. You may recall the film The Danish Girl (2015) with Eddie Redmayne and Alicia Vikander, which was loosely based on Gerda and Einar Wegener’s story. Gerda painted her husband Einar in women’s clothing because her model could not keep her appointment. Then Einar (born on December 28, 1882) gradually transformed into his feminine alter ego Lili Elbe, who cross-dressed in public with Gerda. Eventually, Lili underwent surgeries to change gender. She died from complications after the last one on September 13, 1931. The paintings in this exhibition come from the early 1920s.

Portrait of Lili Elbe with a green feather fan, Gerda Wegener 1920, Public Domain

Perhaps, the most significant subject for this exhibition appears in the galleries of women cast in the traditional art model roles (women “without makeup”) and yet interpretated from a female perspective. Motherhood, the nude model, the nude self-portrait, and the Cubist nude, present the female body as it is lived: unglamorized, unidealized, fleshy, and at peace with one’s present reality, as we see in the Spanish artist Maria Blanchard’s Motherhood (Maternité) from 1922. Neither Madonna nor whore, the female artist presents the female body as a paragon of dignity and grace.

To learn about all the categories created for this innovative exhibition about women artists, please watch the virtual tour led by the chief curator Camille Morineau, and the associate curator Lucia Pesapane. The curators walk through the 9 sections that organize the artworks in terms of subject matter:

- Women at the Front (The “Fourth” Army)

- How Does the Avant-garde Interact with the Feminine?

- Making a Living through One’s Art

- Les Garçonnes

- Representing the Body Differently

- Two Friends

- The Third Gender

- The Amazon

- Pioneers of Diversity

Altogether there are 45 artists included in the exhibition. Among them are Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973), Alice Bailly (1872-1938), Aleksandra Belcova (1892-1981), Anna Béöthy-Steiner (1902-1985), Maria Blanchard (1881-1932), Romaine Brooks (1874-1970), Marcelle Cahn (1895-1981), Claude Cahun (1894-1954), Émilie Charmy (1878-1974), Franciska Clausen (1899-1986), Irène Codreanu (1896-1985), Lucie Cousturier (1876-1925), Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979), Germaine Dulac (1882-1942), Gisèle Freund (1908-2000), Natalia Gontcharova (1881-1962), Alice Halicka (1895-1975), Nina Hamnett (1887-1956), Rita Kernn-Larsen (1904-1998), Marie Laurencin (1883-1956), Stefania Lazarska (1887-1977), Tamara de Lempicka (1898-1980), Sarah Lipska (1882-1973), Marevna [Vorobieff] (1892-1984), Jacqueline Marval (1866-1932), Marlow Moss (1889-1958), Mela Muter (1876-1967), Chana Orloff (1888-1968), Anton [Anna] Prinner (1902-1983), Anna Quinquaud (1890-1984), Juliette Rocher (1884-1980), Germaine de Roton (1889-1942), Amrita Sher-Gil (1913-1942), Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943), Suzanne Valadon (1863-1938), Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875-1942), Marie Vassilieff (1884-1957), and Gerda Wegener (1886-1940).

The list of artists is quite long, and many names may be unfamiliar to you now. Here at Bonjour Paris, we already published a few biographical articles on Sonia Delaunay, Jacqueline Marval, Suzanne Valadon, and Josephine Baker. We also have articles about women mentioned in the show: Jane Poupelet, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas. And we have a wonderful article “Another Side of Paris-Changes in Morality,” about the heady days of Paris during “les années folles” when all kinds of people realized their desire to live unconventionally in the City of Light.

Suzanne Valadon, Young Woman in White Stockings, 1924, oil on canvas, 73 x 60 cm, Nancy, Musée des Beaux-Arts, © Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy, photo G

Lest we forget, dear readers, Paris played a major role in the lives of the artists included in this extraordinary exhibition. It provided acceptance and a liberating creative environment that inspired their artwork. Paris was an art mecca during this transitional era between the wars, a place to find like-minded colleagues and quirky outcasts who fit into numerous Parisian margins. Ernst Hemingway called it “a moveable feast,” poignantly illustrated in our 2015 article “Scenes from Hemingway’s Paris.”

We may be in the middle of a similar moment, influenced by similar circumstances, such as a pandemic, economic extremes, and political tensions around the globe. Perhaps, these women artists can teach us how to cope and how to survive through the study of their art, born of uninhibited imagination and hard-won, fulfilled dreams.

Pionnieres – couverture du catalogue

For more information about Pioneers: Women Artists During the Roaring Twenties (Pionnières: Artistes dans le Paris des années folles), please click on these links: website, a written guide to the exhibition, a short video, the video tour, and the catalogue.

For information about AWARE: Archives for Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, read this interview with chief curator Camillle Morineau and the Cultural Services in the French Embassy of the United States.

Pioneers: Women Artists During the Roaring Twenties (Pionnières: Artistes dans le Paris des années folles) at the Musée du Luxembourg opened on March 2 and closed on July 10, 2022.

Lead photo credit : Photograph of the exhibition Pionnières. Artistes dans le Paris des années folles, Musée du Luxembourg scénographie Sylvie Jodar © Rmn-Grand Palais / Photo Didier Plowy

More in art exhibitions, Les annees folles, Musee du Luxembourg, The Roaring Twenties, Women Artists, women in art

REPLY