When Impressionism Invaded the Louvre: The Isaac de Camondo Bequest

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Class, between 1873-1876, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

The Musée du Louvre had a longstanding rule: no artworks created by an artist who died within the last 10 years could enter the permanent collection. Count Isaac de Camondo changed all that. Having promised his enormous collection (804 pieces) of old and contemporary artworks to the Louvre in 1897, then signing an agreement on December 18, 1908, he singlehandedly engineered the invasion of Impressionism into the hallowed halls of France’s most conservative art institution. Moreover, the museum had to accept works by artists who, on the day of the count’s death (April 7, 1911), were still living: Degas, Renoir, and Monet.

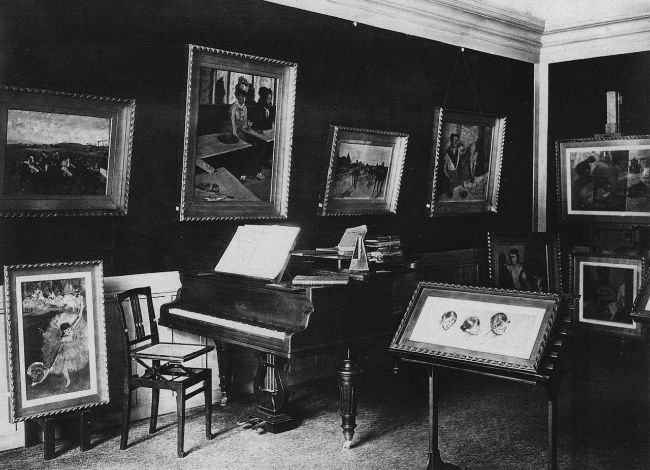

The ”Degas” room in Count Isaac de Camondo’s home at 82, Avenue Champs-Élysées.

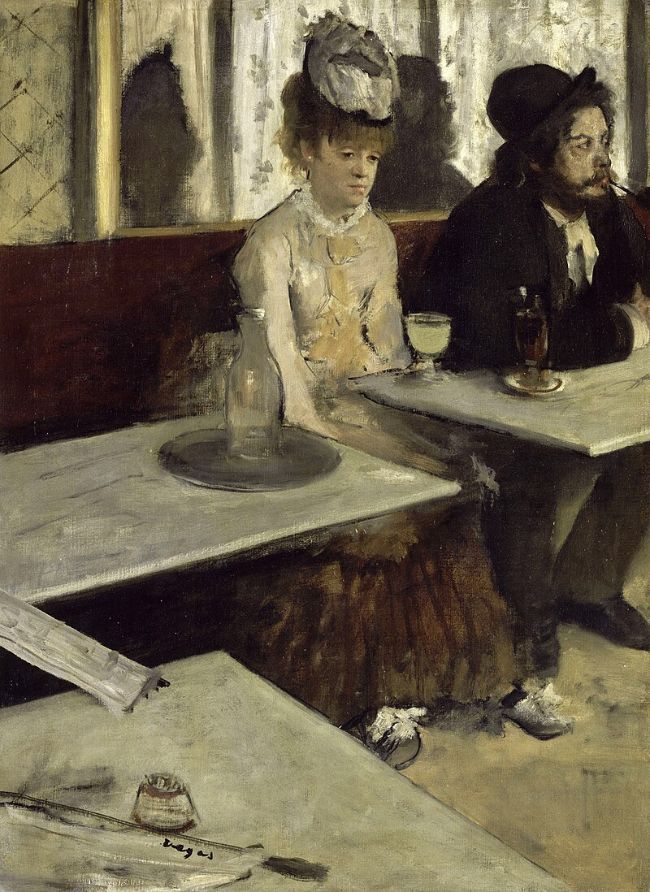

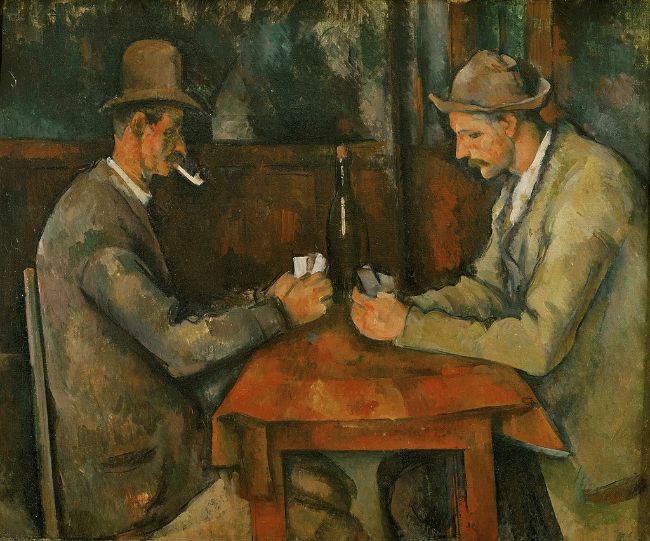

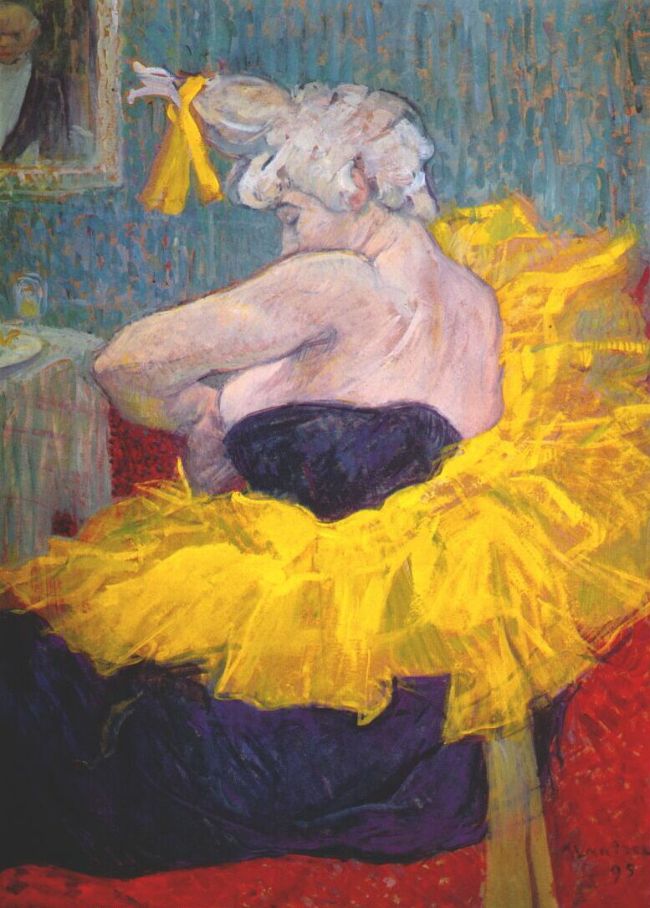

It was a generous gift of paintings, prints, decorative arts, and furniture, from the Middle Ages through the early 20th century, from Europe and the Far East. Among the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings and works on paper were 26 Edgar Degas (1834-1917), 14 Claude Monets (1840-1926), three Pierre-Auguste Renoirs (1841-1919), eight Albert Sisleys (1839-1899), two Camille Pissarros (1830-1903), nine Paul Cézannes (1839-1906), one Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), and one Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901). In concert with these late-19th century moderns was Camondo’s extensive collection of Japanese prints (over 400), sculptures, and decorative objects, evidence of his early embrace of Japonisme which influenced Degas and van Gogh.

Count Isaac de Camondo’s home at 82, Avenue Champs-Élysées.

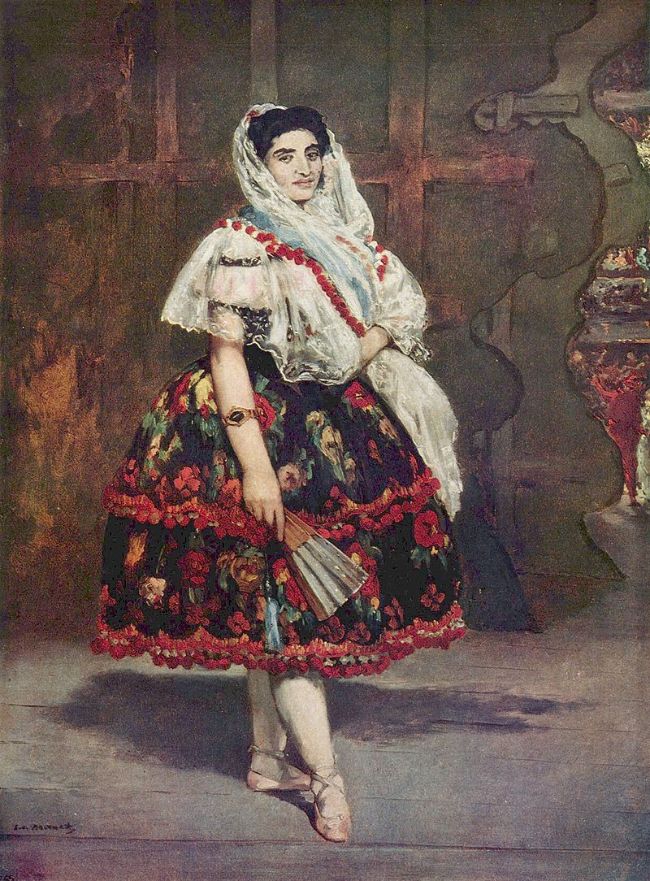

Additionally, he gave the Louvre 11 works by Édouard Manet (1833-1883), a friend and mentor to the Impressionists but not an official member, plus numerous other works (paintings and works on paper) by various more acceptable 19th century artists: Camille Corot (1796-1875), Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), and Claude Monet’s principal mentors Johann-Barthold Jongkind (1819-1891) and Eugène Boudin (1824-1898). Unlike his conservative cousin Moïse de Camondo (March 15, 1860-November 14, 1935), who surrounded himself with authentic, 18th-century, French art and objects, which he donated to France along with his house, the Musée Nissim de Camondo, Isaac de Camondo used his munificence to quietly affect a revolution in the history of art.

Salle Isaac de Camondo. Musée du Louvre

The Louvre begrudgingly accepted the terms of Camondo’s Bequest evidenced in their setting a limit to the period the moderns would be their unwelcome guests: only 50 years. The museum also fulfilled Camondo’s demand for an exclusive suite of galleries bearing his name. To assist in this construction, the count donated 100,000 francs to cover expenses with the proviso that the Salle de Donation Camondo must preserve the appearance of his home on the Champs-Elysées.

Édouard Manet, Lola de Valence, 1862, oil on canvas. Public Domain : Wikipedia

After the required 50 years, the Louvre dispersed the Camondo Bequest among five state museums: the Musée du Jeu de Paume (later transferred to the Musée d’Orsay in 1986), the Musée Guimet – National Museum of Asian Art, the Louvre (Medieval through early 19th century), and the Musée National de la Marine. Meanwhile, most of his Realist, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings became iconic examples of these modernist movements.

Édouard Manet, The Fifer, 1866, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

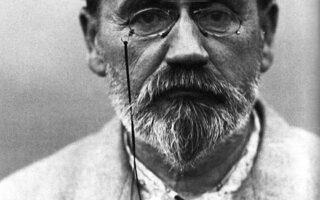

Who was this Count Isaac de Camondo and why did the administrators of the Louvre break their rule to please him? In 1897, he was the head of one of the wealthiest families in Paris (“The Rothschilds of the East”). Also, that year he founded, along with other distinguished benefactors, the Société des Amis de Louvre. Two years later, he served as a consultant for the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, a precursor to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Born in Constantinople on July 3, 1851, Isaac de Camondo belonged to a family that inherited multiple nationalities and yet took pride in their French education and their French way of life.

Édouard Manet, The Lemon, 1880, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

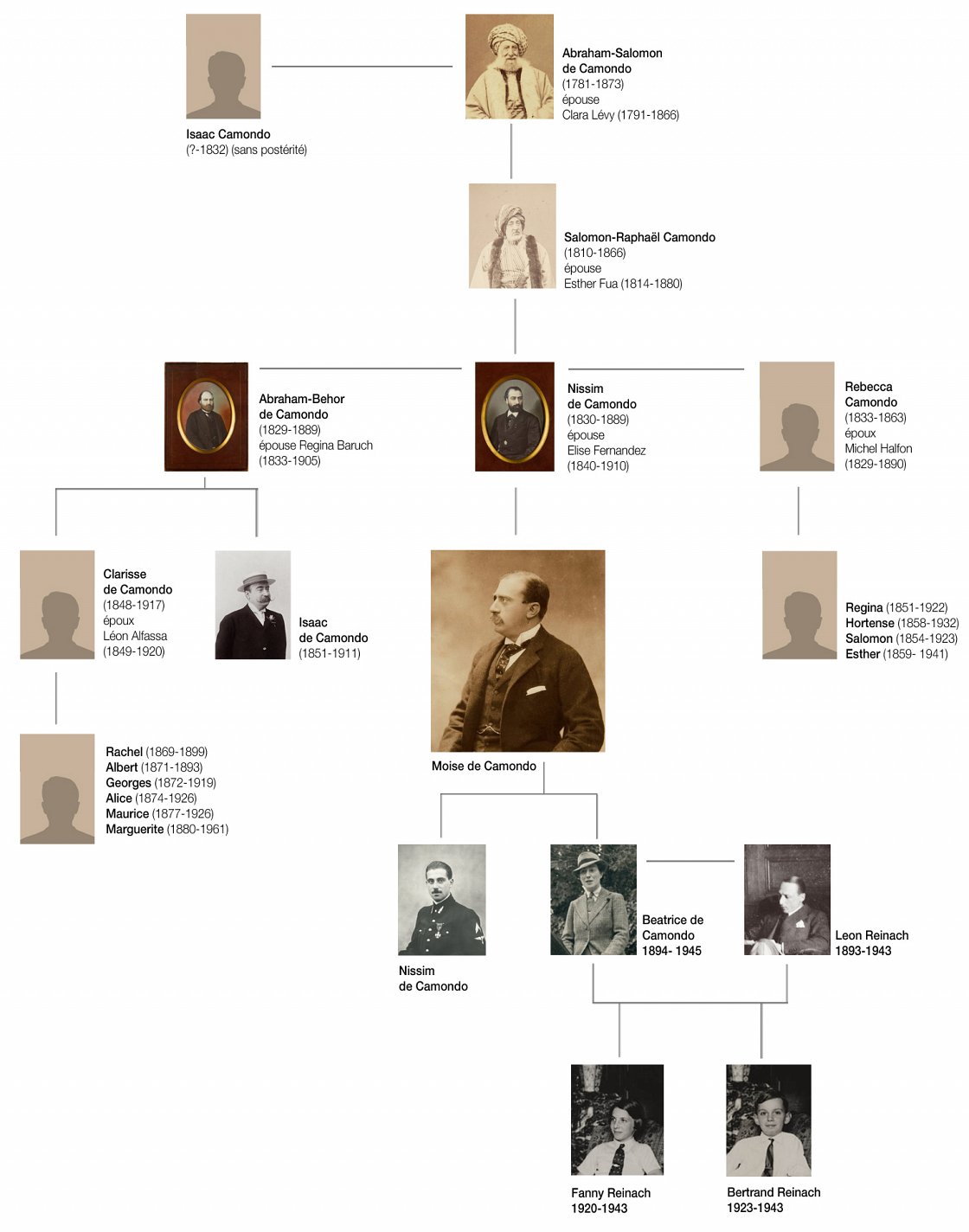

The Camondos’ story begins in Spain, around 1492, with the Expulsion of the Jews during the Spanish Inquisition. Observant Sephardim, the Camondo family chose to emigrate, rather than convert to Catholicism. They migrated toward the east, by way of Trieste first, then they settled in Venice, probably after 1532. As Jews in Venice, they were required to live in the Jewish ghetto, a warren of several streets that confined the Jewish population to one section of the city.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874, en grisaille, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

By the middle of the 18th century, the Camondo family lived in Constantinople, but retained their Austrian status acquired in Trieste and continued in Venice. From this foreign position, the Camondo family enjoyed privileges that protected their Bankhaus Isaac Camondo et Cie, founded in 1802 by Solomon-Jacob Camondo and his sons Abraham Solomon and Isaac, who died 30 years later from the plague. Upon his death, Abraham Solomon inherited the bank, which served as a significant financial resource for the Imperial Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War (October 1852-February 1856).

Edgar Degas, The Tub, 1886, pastel. Public Domain: Wikipedia.

Abraham Solomon also diversified his business dealings by investing in retail, olive oil, and brick manufacturing, and he owned real estate, which was unusual for Jews in Constantinople. His vast fortune supported the Institute Isaac Camondo, founded in 1858, which educated poor Jews in the Peri Pasha section of Constantinople. There they studied Turkish, French, and skills such as tailoring and shoemaking. Extending the family’s humanitarian reach, Abraham Behor de Camondo, Isaac de Camondo’s father, became the president of the central committee of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Constantinople in 1864. This educational organization believed in securing human rights and self-sufficiency for Jews in the Mediterranean, Iran, and Ottoman Empire by creating schools based on a French curriculum.

Edgar Degas, The Absinthe Drinkers, 1885, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

In 1866, Abraham Solomon’s only son, Raphael Solomon, died from a sudden heart attack. His wife Clara died the same year. Perhaps this trauma led to the decision to leave Constantinople. The family had already lent money to the Suez Canal project (1859-69), led by Frenchman Count Ferdinand de Lesseps. Therefore, Abraham Solomon and his grandsons, Abraham Behor and Nissim, viewed France, particularly Paris, as a cosmopolitan center bent on modernization, a fertile ground for their business interests and goals. The year was 1869. On July 19, 1870, the Franco-Prussian War broke out and the Camondos fled to London. Meanwhile they had already acquired land in Paris. Upon returning to Paris they built their homes at 61 and 63 rue de Monceau, in the 8th arrondissement, along with other wealthy immigrant Jewish families, such as the Éphrussis.

Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral: The Door, Morning Sun, Blue Harmonie, 1892-93, oil on canvas. Acquired by Count Isaac de Camondo in 1894. Public Domain: Wikipedia

Alfred Sisley, Flood at Port-Marly, 1876, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

By then, the Camondo nationality had shifted from Austrian to Italian, due to the Unification of Italy in 1861. In recognition of their financial support of the new regime, King Victor Emmanuel II bestowed upon Abraham Solomon, Abraham Behor, and Nissim the noble title “count,” which they would pass onto Isaac and Moïse.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Woman Combing Her Hair, c. 1910, oil on canvas. Purchased by Count Isaac de Camondo in 1911. Public Domain: Wikipedia

In 1872, the year before he died, Abraham Solomon arranged for a partnership with the Banque de Paris et Pays-Bas (renamed Paribas in 1982). Four years later, in 1876, Abraham Behor became a member of the Banque de Paris et Pay-Bas board of directors. Thirteen years later, the inseparable brothers Abraham Behor (July 1, 1829-December 13, 1889) and Nissim (September 10, 1830-January 17, 1889) died within a year of each other. Abraham Behor’s son Isaac, now 38 years old, and Nissim’s son Moïse (March 15, 1860-November 14, 1935), only 29, inherited the Banque Isaac Camondo et Cie in Constantinople and all their parents’ assets.

Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, 1894-85, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

Isaac took the lead until his retirement in 1890, when he closed the bank in Turkey. From then on, he chose to serve as director of several companies, such as Banque de Paris et Pay-Bas (beginning in 1901), the Compagnie générale du gaz pour la France et l’étranger (founded in 1879 by Albert Ellisen and financed by Abraham Behar de Camondo and Louis Stern), and the Compagnie des chemins de fer andalous (the Andalusian Railroad Company), as well as other enterprises. In 1906, Isaac and Moïse liquidated the Bank Isaac Camondo et Cie. In 2000, the National Bank of Paris and Banque de Paris et Pay-Bas became BNP-Paribas.

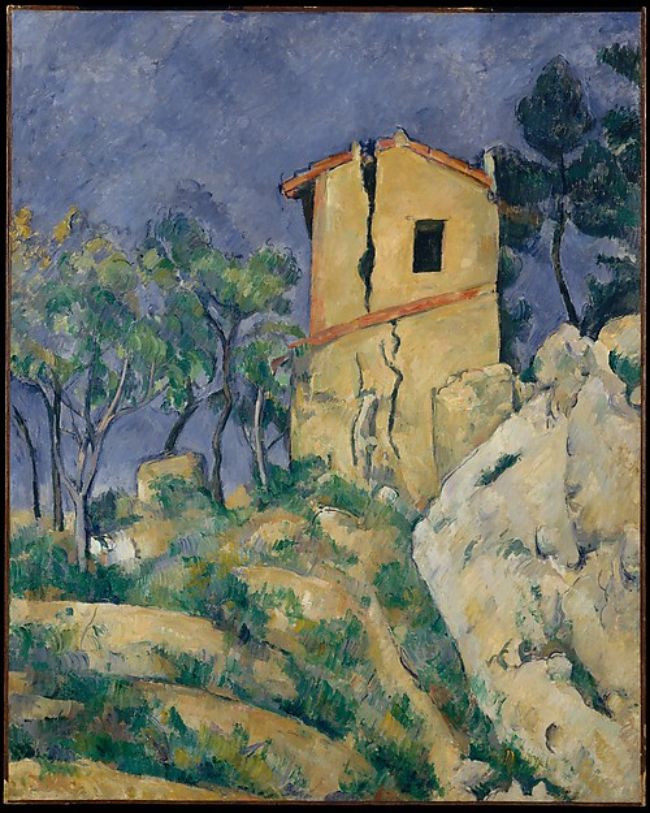

Paul Cézanne, The House with Cracked Walls, 1892-94, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

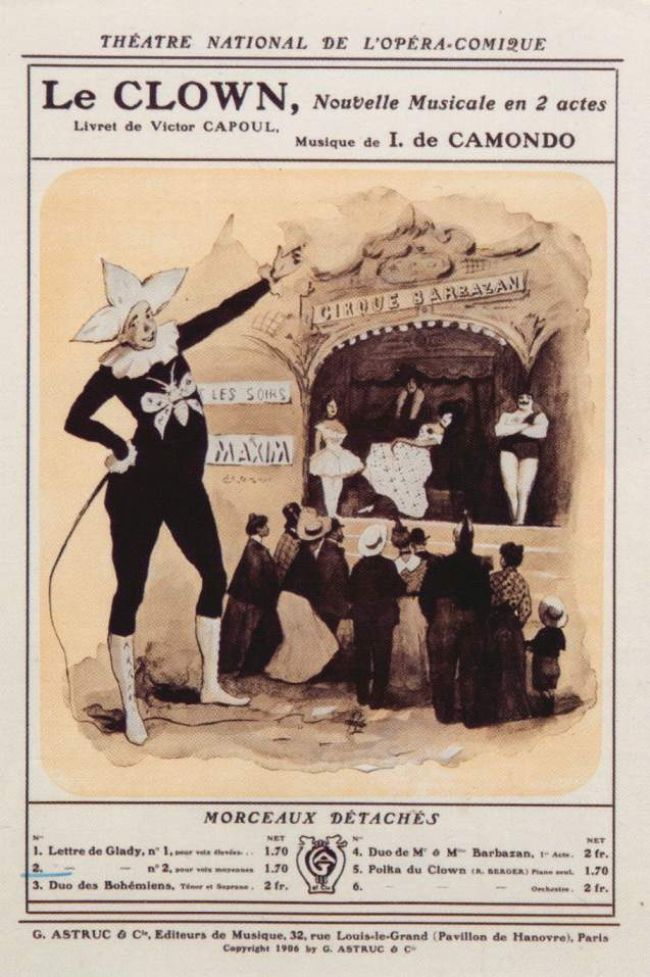

Although Isaac controlled the bank and other family investments to a greater extent than Moïse, who preferred a life of leisure, he also developed his passion for music. He composed his own opera Le Clown, performed in 1906 at the Théâtre Nouveau, and then later in 1908 at the Théâtre National d’Opéra-Comique. He also financed the founding of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with his friend the theatrical impresario Gabriel Astruc.

Poster for Le Clown, 1908. Public Domain: Wikipedia

For decades, the Camondo family’s contributions to France were considerable. And yet, Count Isaac de Camondo’s identity as an immigrant and a Jew during the Dreyfus Affair (1894-1906) invited antisemitic slights that he dealt with diplomatically. For example, James McAuley described in his book The House of Fragile Things: Jewish Art Collectors and the Fall of France (Yale University Press, 2021) that representatives from the Louvre offered Count de Camondo the presidency of the Société des Amis du Louvre in February 1911, but not a position on the Commission des Musées Nationaux, which automatically came with the presidency. The Commission oversaw all of France’s state museums. What was their reason? They claimed his foreign origins compromised his affinity for le patrimoine français. In a letter dated February 15, 1911, Count Isaac de Camondo declined the invitation, pointing out that his status as a “foreigner” did not mean he was a “stranger” to French culture. He then reminded the Louvre administration to honor their agreements for his promised bequest. He died two months later.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Clownesse Cha-U-Kao, 1895, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

A year after the bequest was announced, André Salmon commented in his book Young French Painting that most people still didn’t like Impressionism: “And yet, a vast majority of ignorant people will not discover (and condemn) the finest Impressionists until the Camondo bequest is finally put on display.” This general resistance occurred as the Fauves, Cubism, and abstraction were coming into their own. Today, it’s hard to imagine a negative reaction to Impressionism and the beloved Vincent van Gogh. “And yet” for many, the terms of his bequest and his triumph over the rules did not sit well, even as the Salle de Donation Camondo opened to the public on June 4, 1914.

Those who championed the avant-garde, like poet/critique Guillaume Apollinaire, chose to gloat: “This collection did not enter the Louvre without some difficulty. When one considers how few really modern works there are at the [Musée du] Luxembourg, one is really astonished to see that the Louvre is now much more avant-garde than the museum ostensibly devoted to the work of living artists.” (Apollinaire on Art: Essays and Reviews, 1902-1918, edited by Leroy C. Breunig and translated by Susan Suleiman, Da Capo/Viking Press, 1972.)

The Camondo Family Flag: Loyalty and Charity. Public Domain: Wikipédia.fr

Camondo Family Genealogy. Wikipedia Commons

Léon Joly de Saint François, Abdullah Frères, Abraham Solomon Camondo, 1868. Public Domain: Wikipedia.org

Therefore, Count Isaac de Camondo’s chutzpah (unapologetic nerviness) cannot be underestimated. It took wisdom and savoir faire, the ability to know how to craft a deal with intentionality and aplomb. The gesture also reflected the Camondos’ complexity. On the one hand, they revered tradition, whether it come from their acquired French heritage or their numerous other identities (Austrian, Italian, and Sephardic Jewish). And on the other hand, they championed modern innovation in industry as well as in the arts. It was a trait cultivated by Isaac’s great-grandfather Abraham Solomon, who represented himself in traditional Turkish clothes while negotiating investments in the Suez Canal and railroads.

Vincent van Gogh, Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Pot, 1887, oil on canvas. Public Domain: Wikipedia

Isaac de Camondo died on April 7, 1911, in his majestic apartment on the Champs-Élysées, where he moved in 1907. Previously he lived on the rue Gluck, not far from his family’s mansion at 61 rue de Monceau, right next door to his cousin Moïse’s home, now the Musée Nissim de Camondo, at 63 rue de Monceau. Isaac sold his family’s home in 1893 to the chocolate magnate Gaston Menier. In 2005, the Paris branch of Morgan Stanley moved into the building.

Nadar, Lucie Berthet in the title role of “Thaïs” by Jules Massenet, 1898. Public Domain: Wikipedia

The count left no heirs. He refused to recognize the two sons whom his mistress the Belgian opera singer Lucie Berthet, aka Lucie Bernard (May 13, 1866-April 25, 1941) gave birth to: writer Jean Bertrand (1902-1980) and actor Paul Bertrand (1903-1978). Therefore, the family name “de Camondo” disappeared with the death of Moïse’s son Nissim on the battlefield during World War I (August 23, 1892- September 5, 1917) and Moïse, who died 18 years later.

Giovanni Boldini, Béatrice de Camondo, 1900, pastel on paper. Public Domain : Wikipédia.fr

Moïse’s second child, Béatrice de Camondo, married Léon Reinach, heir to the wealthy and scholarly Reinach family. Their two children were Fanny and Bertrand. Béatrice divorced Léon and converted to Catholicism. Nevertheless, the whole family was arrested by the Nazis during the Occupation, sent to Drancy and then to Auschwitz, where they all perished. The journalist James McAuley in House of Fragile Things and the artist Edmund de Waal in Letters to Camondo (Farrar, Straus and Groux, 2021) conclude that Béatrice foolishly believed the magnanimous donations from her family and her conversation to Christianity would protect her from the Nazi roundups of the Jews.

She was mistaken. All the de Camondos’ acquisitions of and contributions to French culture did not save them. James McAuley’s theme is that although the Camondo family tried to assimilate into Parisian society through supporting French industry and French culture, they were never fully accepted nor respected for their loyalty to France.

Still, let us remember Gaston Migeon’s closing remarks in his essay for the Camondo Collection catalogue: “The gift that Count Isaac de Camondo made to France is inestimable, because it had been made with a steadfast understanding of museum’s real interests and increases the riches of our country. The generosity of his intentions is known to everyone because he repeatedly affirmed them. This is high praise for someone who remained true to himself.”

Sources:

La Splendeur des Camondos de Constantinople à Paris (1806-1945), Paris : Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaïsme, November 6, 2009 – March 7, 2010. website and catalogue.

Gaston Migeon et al., Le catalogue de la Collection Isaac de Camondo Bequest, Paris : Gaston Braun, 1922 Musée du Louvre catalogue,

Video on Isaac de Camondo presented by curator Sylvie Patry at the Pushkin Museum, 2019, in coordination with an exhibition about the Russian collector Shchukin. (In Russian, English and French)

Lead photo credit : Portrait de Isaac de Camondo, c. 1908. © Musée des arts décoratifs, Paris.

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY