A Proustian Moment in New York: The Ephrussi-de Waal Collection

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

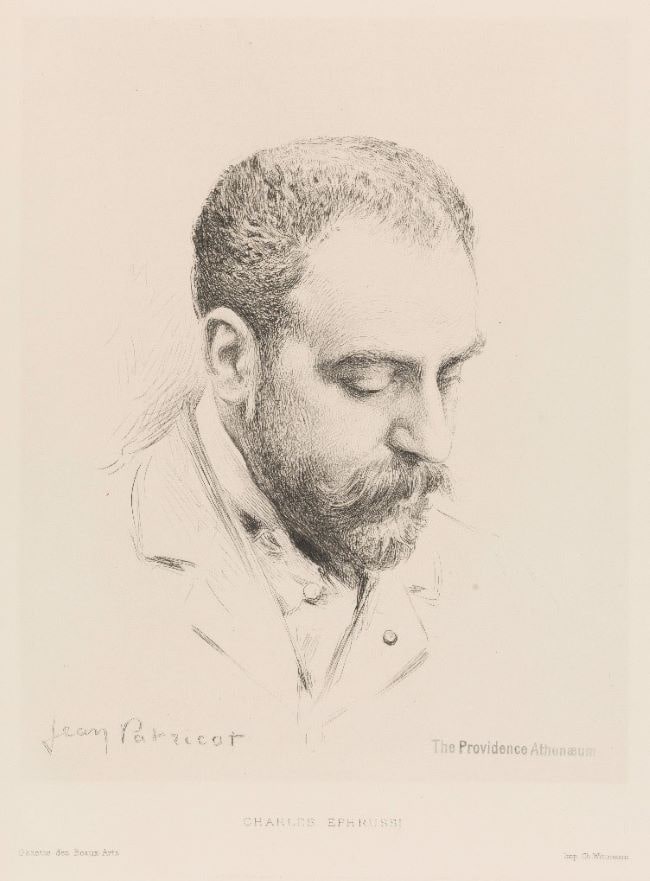

Proust fans rejoice! Last year we celebrated the 150th anniversary of Marcel Proust’s birth on July 10, 1871. This year we honor the 100th anniversary of Proust’s death on November 18, 1922. In Paris, Proust’s bed and other personal effects remain on view at Musée du Carnavalet, even though their splendid exhibition Marcel Proust, A Parisian Novel, closed on April 10th. Four days later, the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme opened their Proust exhibition, focused on the author’s Jewish roots through his mother Jeanne Clémence Weil. This illuminating investigation of a delicate subject among Proust readers will close on August 28th. Outside Paris, the temporary Marcel Proust Museum at 19 rue de Chartres in Illiers-Combray opened on January 22nd, displaying contents from Aunt Léonie’s House at 4 rue de Docteur Proust, which is in the midst of renovation through 2023. And in New York, at the Jewish Museum, we have a minor homage to Proust in their exhibition of Charles Ephrussi’s netsuke collection. Ephrussi was allegedly one of the models for the debonair major character Charles Swann in Proust’s seven-volume masterpiece À la Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time), 1913-27. (The other model may be Charles Haas.)

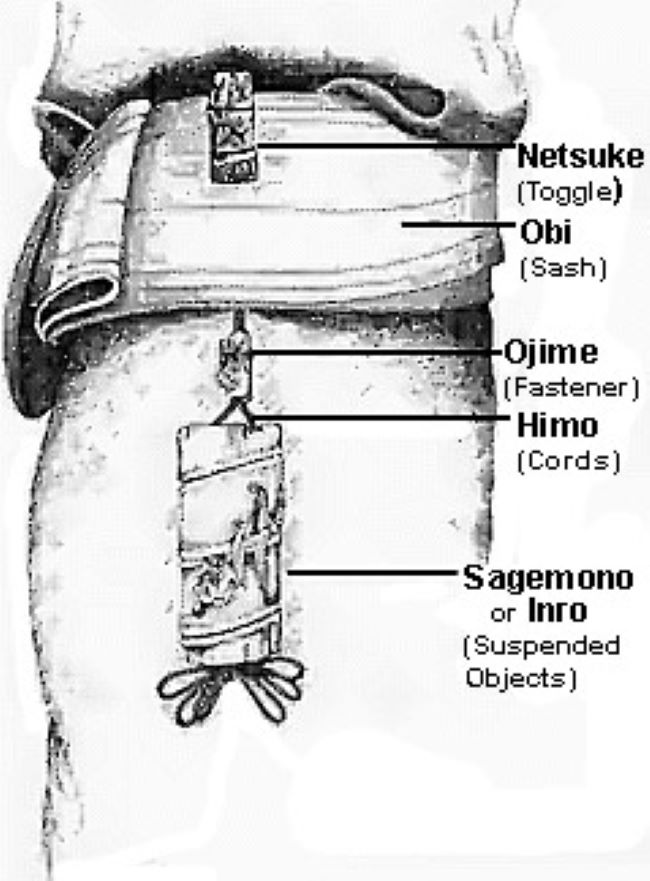

Netsuke diagram illustration

Charles Ephrussi’s impressive collection of Japanese netsuke from the Edo Period (17th-19th century) reflects a discerning eye for these garment toggles carved out of ivory or wood in the shape of animals, people, natural objects, and fanciful demons, among other subjects. The Jewish Museum’s curators Stephen Brown and Shira Backer divided 168 pieces into three display tables and one display cabinet, one per gallery, in an effort to connect their remarkable story with the history of a very wealthy Jewish family from Odessa, Ukraine.

Recumbent hare with raised forepaw, signed Masatoshi Ivory, eyes inlaid in amber colored buffalo horn Osaka, Japan, ca. 1880, de Waal family collection

The Ephrussi dynasty amassed their fortune from grain and banking, conducting their business in Vienna and Paris from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century, when the Nazis invaded their homes and confiscated almost everything. The Jewish Museum’s exhibition (November 19, 2021-May 15, 2022) is based on the book The Hare with Amber Eyes written by the last heir to the netsuke collection, British artist Edmund de Waal, an accomplished potter whose elegant work would have added a beautiful post-script to this rather understated introduction to the Ephrussis’ opulence. Dutch photographer Iwan Baan captured the current state of the former Ephrussi homes in Paris and Vienna, now transformed into business offices. These large flat images, hung throughout the exhibition, provide a poignant record of absence. Gone are the valuable artworks, artifacts, and furnishings which the exhibition designers Diller Scofidio + Renfro present in period-matching vitrines. The entry text explains that the four netsuke display cases in four different galleries represent the four owners of the collection, passed on from generation to generation: Charles Ephrussi to his uncle’s son Viktor and his wife Emmy Ephrussi to their son Ignace Ephrussi, and to Edmund de Waal, Iggie’s grandnephew.

The Hare with the Amber Eyes: The Charles Ephrussi/Edmund de Waal Collection at the Jewish Museum, November 19, 2021-May 15, 2022, Photo: Beth S. Gersh-Nesic

Of the original 264 netsuke purchased by Charles Ephrussi during the 1870s, only 168 are displayed in glass-covered tables and one cabinet. Another 79 pieces are projected on the wall in the last gallery. The 2018 sale of the latter raised funds for the Refugee Council, a charitable organization that aids refugees and other people seeking asylum in the UK. In this last room, a label explains that 157 netsuke are on long-term loan to the Jewish Museum of Vienna.

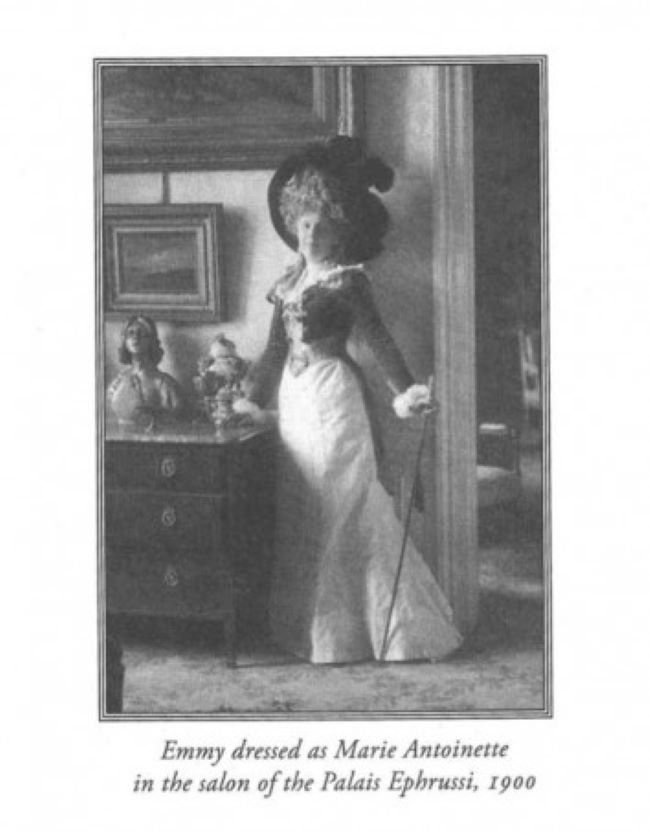

De Waal – Emmy dressed as Marie Antoinette in the Salon of the Palais Ephrussi, 1900 (Idlewildbooks.com)

All the netsuke and their cabinet were shipped from Charles Ephrussi’s residence in Paris to Viktor and Emmy Ephrussi’s home in Vienna as a wedding gift in March 1899. “He was thirty-nine and in love; and she was eighteen and in love. Viktor was in love with Emmy. She was in love with an artist and a playboy who had no intention of marrying anyone, let alone this young decorative creature. She was not in love with Viktor.” (The Hare with Amber Eyes, p. 136)

Installation view of The Hare with Amber Eyes, the Jewish Museum, NY, November 19, 2021-May 15, 2022. Photo by Iwan Baan

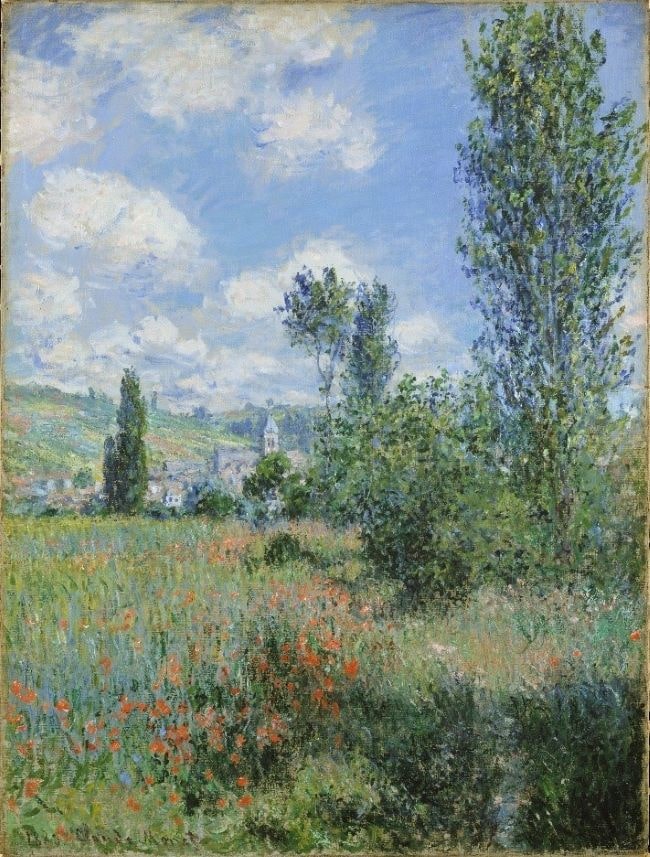

In addition to the netsuke collection, several of Charles Ephrussi’s fine art paintings appear in situ or as photographs on a partition wall located in the first room. Sadly, Manet’s exquisite A Bundle of Asparagus (1880) was only a sepia reproduction placed right below Claude Monet’s luminous View of Vétheuil, (1880). These Asparagus paintings inspired a Proustian satire in his third volume, Guermantes Way (1920). The true incidence occurred when Charles Ephrussi paid Manet 1000 francs for the commissioned Bundle of Asparagus originally priced at 800. To express his appreciation, Manet sent back a single asparagus painted on a small canvas with a note: “This seems to have slipped from the bundle.” (A Sprig of Aparagus, 1880). Proust must have heard the story and, perhaps, seen the two paintings in his friend’s home. Forty years later, he remembered the paintings and referenced them obliquely to shed light on the conservative taste of the self-satisfied old guard. At his own dinner party, Proust’s character the Duc de Guermantes complains about the ridiculous price of a painting of asparagus by the novel’s fictional modernist artist Elstir: “He asked three hundred francs. A Louis, that’s as much as they’re worth, even if they are out of season. I thought it was a bit stiff.” (translated into English in The Hare with Amber Eyes, p. 76).

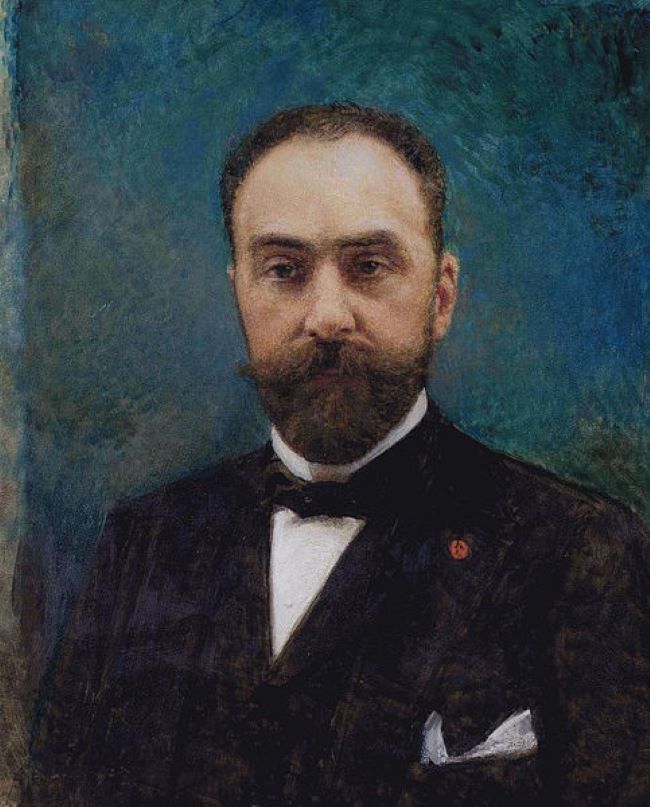

But what about Charles Ephrussi himself? What can we learn about this real person in the Jewish Museum’s exhibition? Does any information here enhance our understanding of Proust’s Charles Swann? What might they have in common? What are clearly the differences between the two? Alas, the portrait of Charles Ephrussi, this fascinating bon vivant art historian and critic, feels far more tepid in this exhibition than in de Waal’s book The Hare with Amber Eyes. Placing his reader at the very beginning of his journey in front of the Hôtel Ephrussi at 81 rue de Monceau, 8th arrondissement, the author describes this majestic home that now houses a rather pedestrian occupant, a medical insurance office. Then de Waal maps out for our imagination the living quarters of the original residents: Charles lived on the second floor in a suite of rooms, his older brother Ignace on the same floor, their widowed mother Mina and an older brother Jules lived in the apartments below. The family moved from Vienna into their Paris mansion during the same summer Proust was born in the 16th arrondissement, 1871.

Hôtel Ephrussi, 81 rue de Monceau, 8th Arrondissement, Wikimedia Commons

Digging deeper into the netsuke collector’s persona, de Waal wrote: “Charles, at forty, was poised between all these different worlds [art, commerce, and the Proustian beau monde]. His private taste had become public property. Everything about him was aesthetic. He was known in Paris as an aesthete whose commissions and pronouncements and cut of jacket were scrutinized. He was a devotee of the Opéra. Even his dog was called Carmen.” (p. 89)

Léon Bonnat, Portrait of Charles Ephrussi, 1906, Private Collection. Credit: Wikimedia commons.

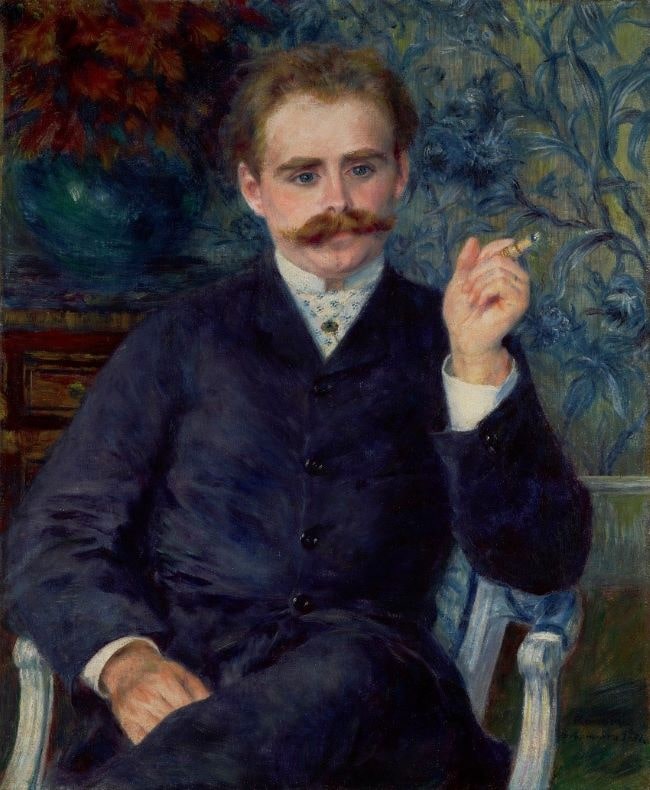

Unlike Charles Swann, Charles Ephrussi limited his romantic liaisons to unmarried bliss. His affair with Madame Louise Cahen d’Anvers became common knowledge, his dalliances with men less so. An attractive strawberry blonde, who was a bit older than Charles, Louise was married to Albert Cahen d’Anvers, a wealthy Jewish banker. They had four children. When the fifth arrived, she named him Charles. (The Hare with Amber Eyes, p. 44)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Albert Cahen d’Anvers, 1881, Oil on canvas, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 88.PA.133

Proust’s wealthy Jewish stockbroker and art afficionado Charles Swann married his mistress Odette, whose reputation as a courtesan (allegedly) ruins Swann’s social life, reducing his access to the beau monde he frequented heretofore. Ephrussi never succumbed to such bad judgement. In fact, his social currency increased as he rose from contributor to co-owner of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, a highly respected journal launched in 1859. Ephrussi joined in 1885 and became co-editor with Roger Marx in 1900 until his death on September 30, 1905. Born on December 24, 1849 (a bit younger than the Impressionists), he died before he reached his 56th birthday.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1881, Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Wikimedia Commons

We can spot Charles Ephrussi in 1880-81 wearing his rather formal black top hat among casual summer straw hats covering the heads of men and women in Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1881 (Phillips Collection, Washington, DC). Ephrussi’s back is to the viewer as he chats up his friend, the poet Jules LaForgue. Distinctive in his fine black jacket and well-trimmed beard, Ephrussi’s aristocratic bearing contrasts noticeably with the sleeveless fellows in the foreground. Although Renoir was antisemitic, he accepted the Ephrussi and Cahn d’Anvers commissions, as we see on the wall in the first gallery of the Jewish Museum’s show.

Opposite the wall of paintings, the exhibition features a vitrine installation dedicated to fleshing out Charles in other ways: his home, his furnishings, his writings (such as his monograph on Albrecht Dürer and a copy of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts), and a few pages of Proust’s novel to help museum visitors understand his connection to Charles Swann.

Palais Ephrussi, converted into stores, at the corner of Ringstrasse and Schottengasse, Vienna

The Hare with Amber Eyes tells three stories: Charles Ephrussi’s biography, the life and legacy of the Ephrussi family, and the precipitous end of the Ephrussis’ formidable power in finance and politics, beginning with the SS’s invasion of their home in Vienna on April 23, 1938. Suddenly aware of Europe’s betrayal as the Nazis destroyed and confiscated as much as they could, Viktor and Emmy’s quickly escaped to their Swiss home with the aid of their oldest daughter Elisabeth, now married and living with her family in England. Miraculously, as all the furnishings and artworks were carted away, the netsuke, these extraordinary miniatures sculptures, survived thanks to the ingenious efforts of the family’s Christian nanny, Anna, who stuffed most of the 268 figures into her mattress while the Nazis sacked and pillaged the Palais Ephrussi on the corner of Ringstrasse and Schottengasse in Vienna. In 1945, she gave all the pieces to Edmund de Waal’s grandmother Elizabeth Ephrussi de Waal, who put them into an attaché case and handed them over to her brother Ignace during his trip to England in 1947. Ignace left Vienna a few years before the Nazi invasion to seek his fortune in New York and then California. At first, he pursued a career as a designer of women’s wear. He also became a U.S. citizen, served as an intelligence officer in the U.S. army during World War II, and afterward, joined General MacArthur’s U.S. post-occupation of Japan. He settled there and so did the netsuke collection. Upon Ignace’s death in 1994, the collection went to Uncle Iggie’s partner Jiro Sugiyama, who died on November 30, 2011. He bequeathed the netsuke collection to Iggie’s grandnephew Edmund de Waal.

A careful study of the netsuke’s fierce demons, winsome rodents, lumbering servants, and overtaxed moms magically transports us into the lost world of 17th-19th century Japanese culture, and into Emmy Ephrussi’s dressing room where the netsuke in their cabinet were on display. As the children watched their mother prepared by her maids for a fashionable social engagement, they were allowed to play with one or two netsuke at a time. Her son Iggie recalled taking out netsuke and dutifully returning each one to its correct place in the cabinet before their loyal nanny Anna shepherded all four children out the door: Elisabeth (1899-1991), Gisele (1904-1985), Ignace Leon Karl (1906-1994), and Rudolf (1918-1971).

Installation view of The Hare with Amber Eyes, the Jewish Museum, NY, November 19, 2021-May 15, 2022. Photo by Iwan Baan

The last two rooms of war photos, memorabilia, and Edmund de Waal’s own cabinet filled with netsuke (along with the projected grid of the 79 sold pieces) testify to the tragedies and triumphs of the Ephrussi family, epitomized by the survival of the netsuke collection itself. Emmy, overwrought after the escape to their home in Switzerland, committed suicide. Her husband Viktor joined their daughter Elisabeth and her family in Tunbridge Wells, England. He died on February 6, 1945, three months before the end of the war in Europe. Elisabeth’s sister Gisele and her family immigrated to Brownsville, Texas. She died in Mexico in 1985. Her brothers Ignace and Rudolf became American citizens and joined the armed forces in World War II. Rudolf died in 1971 in New York.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Aurora Triumphing Over Night, about 1755-56 Oil on canvas Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Hare with Amber Eyes exhibition and book recount yet again the resilience of the Jewish people and the courageous non-Jews who also risked their lives during this existential crisis. The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance (Vintage, 2011) is available in bookstores and online. For further information about the Ephrussi family and their Jewish peers in Paris, read Edmund de Waal companion book Letters to Camondo (Penguin Press, 2021) and The House of Fragile Things: Jewish Collectors and the Fall of France by James McAuley (Yale University Press, 2021). The exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York is based on the exhibition The Ephrussis: Travel in Time, on view at the Jewish Museum in Vienna from November 6, 2019 to March 8, 2020. The catalogue from the latter is available through the museums’ websites.

Lead photo credit : Jean Patricot, Charles Ephrussi, 1905, Drypoint, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., Museum Purchase, 2016

More in Ephrussi-de Waal Collection, Marcel Proust Museum, Musée du Carnavalet, Proust, Proust Exhibition, The Jewish Museum