Émile Zola: The Influential Journalist Turned Novelist

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

As France celebrates the 150th anniversary of Impressionism, Anne Price looks at Émile Zola’s role in glorifying the art movement

Long before Edison, Tesla and the City of Light, Paris was a dark, chaotic mess, with huge tracts of the city being reduced to rubble to accommodate the vision of Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann in a quest to remodel the city. Montmartre, thought to be too hilly to develop, escaped the sledgehammers and watched as the city was systematically razed to the ground around it. At the foot of the hill, the village of Batignolles became the haunt of artists, writers and poets where cafes and bars thrived. It was here that a young writer, whose early Bohemian lifestyle drew him to the artistic community of Paris, met a group of revolutionary, young artists with whom his life became inextricably bound.

It was only recently that I realized that Émile Zola’s relationship with this radical group of artists was fundamental to the start of his career in journalism. He is one of the most influential and controversial figures in the history of French literature. His novels, which paint detailed portraits of the dark, desperate conditions of working-class, industrialized France, owe their success to his journalistic approach to research.

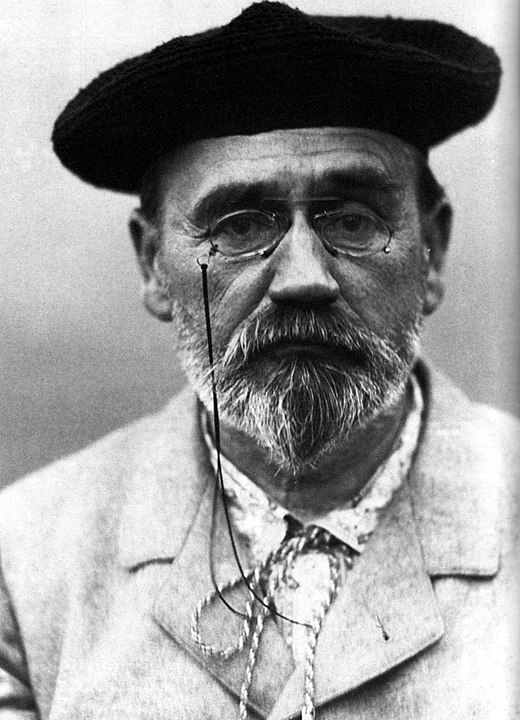

Frédéric Bazille, L’Atelier de Bazille, 9, rue la Condamine, (1870). Zola is represented on the staircase. Public domain

My enduring schoolgirl image of Émile Zola is of a shadowy figure creeping around sewers and brothels in the underbelly of Paris with his notebook, interviewing people on whom he based characters like that of Thérèse Raquin who, together with her lover Lantier, murdered her husband; or Gervaise, the laundry owner of L’Assommoir, who had her eternal optimism crushed by circumstances beyond her control, destined to die alone; and her willful daughter Anna, who became the infamous courtesan Nana, destroying men while accumulating their fortunes and whose death from smallpox is described in the most horrific way. Everyone wanted to read them, even if some of them were read furtively. Nana, one of the 20-volume Rougon-Macquart series, sold out 55,000 copies in one day. They also made him very wealthy.

Auguste Renoir, La Loge, (1874). This work illustrated the pocket edition of “Nana” for a long time.

Zola was born in Paris to a French mother and Venetian father, who struggled to have his engineering projects accepted. Eventually he succeeded and when Emile was 3, the family moved to Aix-en-Provence where he secured the task of designing the dam which still bears his name today. Flushed with success, his father lived beyond his means, accumulating huge debts in the process. He died suddenly when Zola was 7, leaving his wife struggling to support herself and her son. In 1852, a scholarship allowed Zola to enroll as a boarder at the Collège Bourbon, where he met Paul Cézanne, a banker’s son, who defended the lonely, puny child against the bullying and abuse he suffered from the other boys.

Zola grew to become a formidable foe, launching himself into freelance journalism, always championing the underdog. He would use this platform to repay his debt to Cézanne in 1866, by launching a blistering attack on the then citadel of artistic taste, the Salon, which constantly rejected Cézanne’s work. It became one of the most important friendships of his life — the first step towards introducing Zola to the world of painters. It endured for 30 years, until it is believed that the two friends fell out over Zola’s novel, The Masterpiece, whose main character, presented as a failed genius, appeared to be modeled on Cézanne. This upset the artist and apparently the two friends became estranged.

Paul Cézanne, “Paul Alexis reading a manuscript to Zola”, 1869

Driven by poverty, Zola’s mother moved back to Paris to find work. She enrolled her son in school, hoping he would become a lawyer. As a result of ill health and general unhappiness, Zola failed his exams. He was lonely, depressed and missing his friends in Aix-en-Province, to whom he wrote constantly, trying to persuade them to join him in Paris. For two years he worked for minimal pay as a clerk in a shipping firm, doing odd jobs and pawning his belongings to get by, before going to work for the publisher Louis Hachette, where he was responsible for sending out press releases for other writers.

Since childhood, Zola had written short stories and novels, and now he found a way to support himself and his mother. For 30 years he wrote every day, living up to his words, “Not a day without a line.” His sordid, semi-autobiographical novel, The Confession of Claude, was eventually finished and published in 1865. It provided Zola with necessary income, but Hachette fired him for bringing the company into disrepute. Zola decided to work independently for various newspapers, contributing critiques of the art and literature of his day.

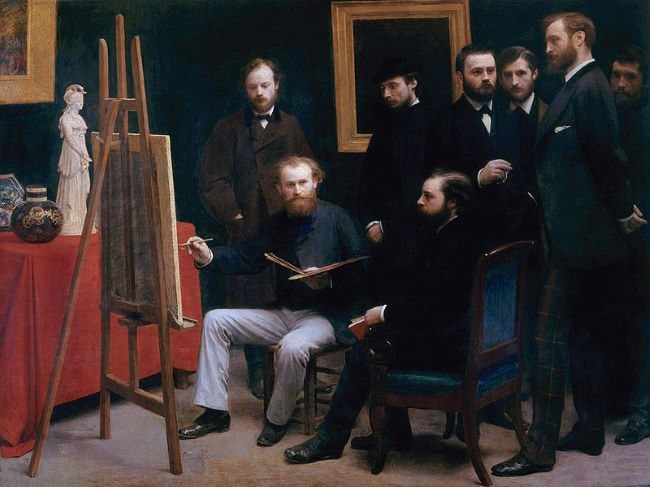

In 1863, Cézanne joined Zola in Paris where he soon became part of the revolutionary art scene. He introduced Zola to Manet, Guillemet and the group of young artists who would breathe new life into painting in France. Zola became a regular at the Café Guerbois and visited studios, befriending many other artists including Monet, Bazille, Degas and Renoir, whose work he heavily defended in his articles as a journalist. From 1866 onwards, he would invite them all to evening gatherings at the home he shared with his future wife, where stimulating debates on art theory inspired his interest in the plein air artists, later named the Impressionists. His notes made at the time capture the almost tangible zest for life of these young people hovering on the edge of an artistic revolution, one which Zola believed could only move forward.

Henri Fantin-Latour, A Studio at Les Batignolles, 1870

Zola did not consider himself a professional art-critic. He was a journalist, who knew how to write well. Early in 1866, Cézanne submitted a work to the Salon which was rejected. After writing two letters demanding the re-establishment of the Salon des Refuses, to which he received no reply, he appealed to Zola to write something in his newspaper. Defending his friend against the bullying of the Salon, Zola responded with a series of articles in L’Evenement, for which he was now working as a book-reviewer.

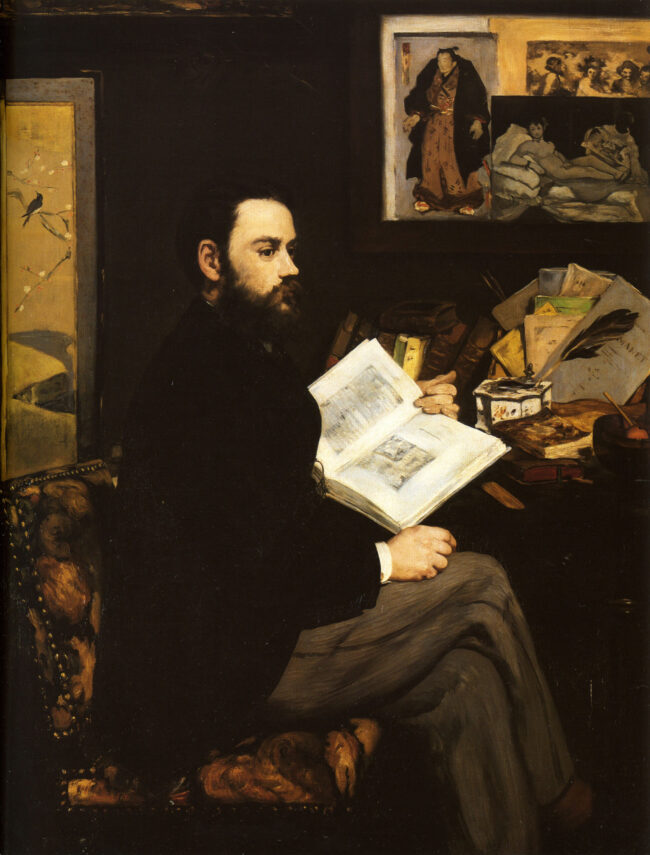

Most of the articles, symbolizing a fight against censorship and reaction, incensed subscribers, resulting in the editor axing the articles and suspending Zola from the paper. Eventually Zola published them separately as a short book called Mon Salon which appeared in May 1866 and was dedicated to Cézanne. He devoted his fourth article to Edouard Manet who also had two pictures rejected by the Salon of 1866. Manet wrote two letters expressing his gratitude for these “remarkable” articles and a painted a portrait of Zola in time for the 1868 Salon. Zola’s fearless stand in defense of Manet and the Impressionists was an attack on the ignorant public, claiming that these artists were the “masters of the future” and should be recognized as such. Zola won a moral victory for himself, wide publicity for his friends, and succeeded in the integration of the critic into a new artistic movement.

Portrait d’Émile Zola by Édouard Manet (1868)

In the 1870s, out of friendship, he helped establish an artistic movement in the eyes of the public. It came at great personal inconvenience, as editors of French papers were reluctant to employ him, but he continued to plead for his friends, although they were now committed to holding independent exhibitions, of which he could not approve. By 1879, he was disappointed by the Impressionists for being too easily satisfied, saying that it is easy to be a pioneer but quite another thing to sustain total victory. With his help, they had achieved what they wanted. Still a Romantic poet at heart, he felt that they did not live up to their potential, never producing an icon like a Delacroix or a Courbet.

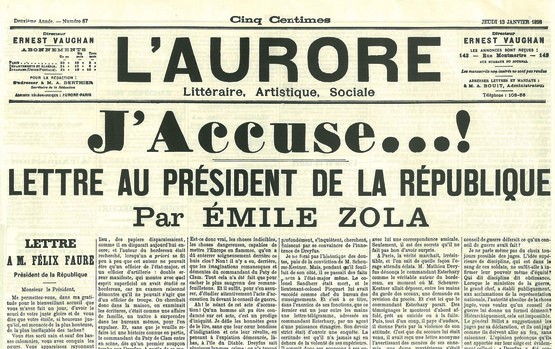

J’accuse !

Zola saw critical journalism as a general moral responsibility. His ideal was always the greatest good of the greatest number. He became more of a revolutionary and he moved on to the causes of the workers. In his novels and his critical articles, he wrote about the heroism of everyday life, from painting to politics, becoming a champion of the ordinary French people. He was outspoken to the point where he said that “real courage is needed to speak the truth everywhere and in everything.” Sadly, he realized that his work as a critic could not coexist with his ideal of friendship. From the idyllic friendships of his youth, Zola became more and more isolated in the cause of his understanding of the truth.

In his early years in Paris, Zola had lived in extreme poverty. He had fought the Impressionist battle, twice losing his job in the struggle, while some of the artists he supported were cushioned by wealthy families. They became critical of his obvious pleasure in the materialism his eventual success and wealth brought him. Zola was equally critical of artists like Monet for catering to the commercial market, even though his novels were making him wealthy. 150 years later, the Impressionists are still the enduring art of the masses, exhibited everywhere, whether on upmarket screen-printed silk scarves, or fridge magnets and mugs produced for the tourist market.

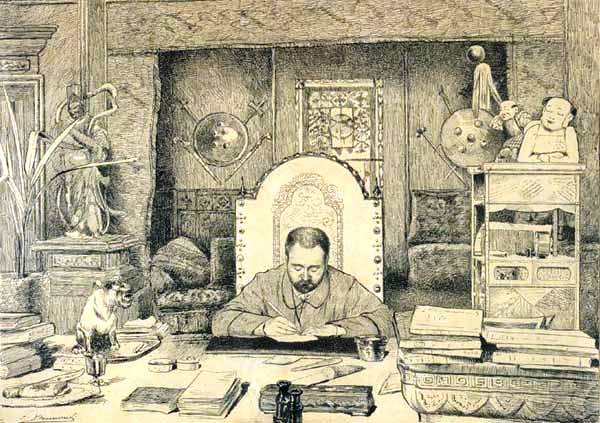

Émile Zola at work in his office. Public domain

Described as possibility the greatest journalist-turned-novelist of the 19th century, Zola embarrassed his contemporaries by trawling the dark side of Paris. A fearless investigator, he put his journalistic skills to good use, giving the dispossessed an identity, interrogating the working classes, even taking his notebook down a mine for his novel Germinal. He criticized Napoleon III in his political articles, as fearlessly as he had demanded equal representation for the Impressionists in the Salon of 1866. During the Franco-Prussian War, he founded the political paper “The Marseillaise”. His opinion column “Pour le Juifs” foreshadowed his series of articles “J’Accuse”, in the infamous Dreyfus affair, resulting in scrutiny of the French military and swaying public opinion. Accused of libel, he was sentenced to a year in prison and a hefty fine. He then fled to England.

Zola died as dramatically as he lived. Details of his unusual family life remain veiled, just as details of his death are only hinted at. He had made a great many nationalist enemies after his defense of Dreyfus, so it was suggested that his death from carbon monoxide poisoning was not accidental. It has never been proven. His name is legendary, and would certainly be near the top of my list of intriguing historical guests around my dinner table.

Emile Zola on his death bed, September 1902. Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Lead photo credit : Portrait of Émile Zola. Unknown author. Public Domain

More in Emile Zola, history, Literature, politics