Picasso in Fontainebleau

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

From July to September in 1921, Picasso rented a villa for himself, his Russian ballerina wife Olga Khokhlova, and their five-month-old son Paul Joseph (“Paolo”) in the charming village of Fontainebleau, about 35 miles from Paris, best known for its glorious, eclectic château, dating back to the 12th century. In the adjacent garage, fitted out as a studio, Picasso created four gigantic masterpieces: Three Musicians (two versions painted simultaneously) and Three Women at the Spring (two versions, one painting and one red-chalk drawing). These 6-foot works towered over 5 foot-4 inch Picasso in this narrow space, generating an enigmatic puzzle for future Picasso scholars: What can we glean from Picasso’s eclecticism during this summer in Fontainebleau?

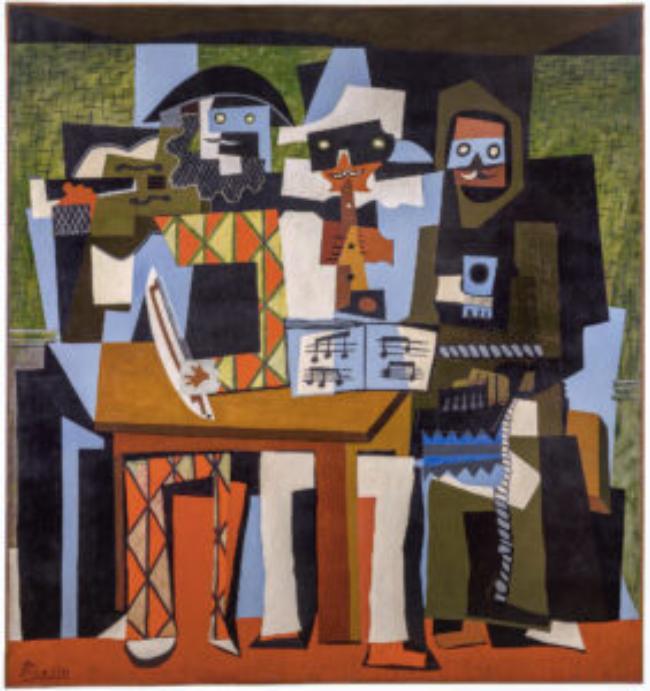

Pablo Picasso, Three Musicians, 1921, Oil on canvas. The Philadelphia Museum of Art. A. E. Gallatin Collection, 1952 ©2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

Willing to take on the challenge and contribution to Picasso 1973-2023: The Fiftieth Anniversary, New York’s Museum of Modern Art brought these four significant works together for the first time since they left Picasso’s Fontainebleau studio in 1921. Anne Umland, the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture, and her assistants, Alexandra Morrison and Francesca Ferrari, examined the works diligently, and then had them installed with other Picasso works completed at the same time in order to study this pivotal period in this artist’s very long and extraordinarily productive career. Their query is: What was Picasso thinking? We have, on the one hand, his late Cubist style for Three Musicians, and, on the other, his “Ingres-esque” classical style for the Three Women at a Spring. What should we take away from this disparate combination?

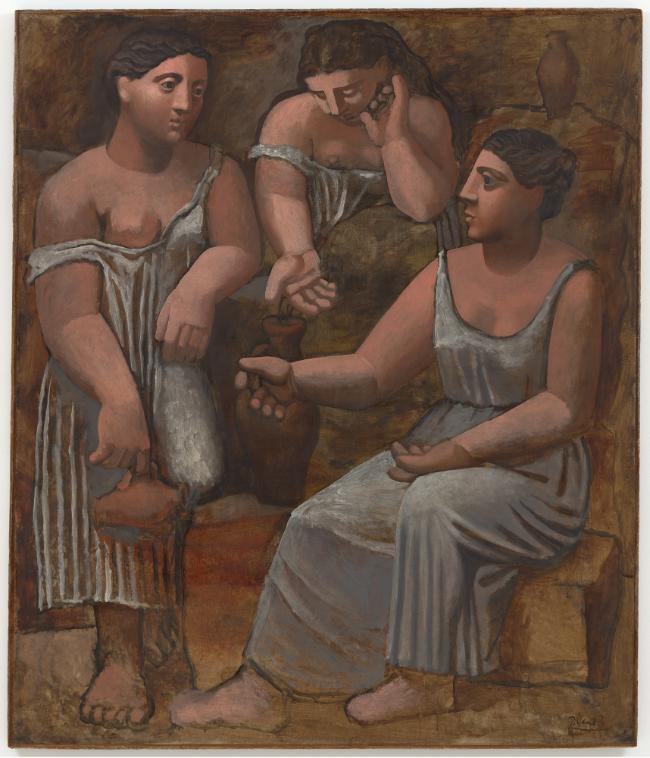

Three Women at the Spring, Fontainebleau, summer 1921, oil on canvas. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Allan D. Emil ©2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

First, let’s consider the brilliant exhibition Picasso in Fontainebleau. We enter into a huge gallery where we see numerous works of art produced within the few years leading up to the summer of 1921. Several come from the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, owner of Picasso’s greatest creations, most notably, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Then we walk through a small, narrow gallery that features ghostly reproductions painted on the walls giving us a feeling for the dimensions inside Picasso’s studio-garage, 20 x 10 feet. From there we emerge into a very large gallery which displays the two versions of the late Cubist Three Musicians (from MoMA and from the Philadelphia Museum of Art), facing each other on opposite walls, and the two versions of his classical Three Women at the Spring, which face each other as well. The musicians are male and the women at the spring are – well, you know.

Installation view of Picasso in Fontainebleau, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 8, 2023-February 17, 2024. © Jonanthan Dorato

It’s an intriguing ensemble of characters. The musicians seem lighthearted as they entertain us with their silent concerts. They belong to the traveling burlesque Commedia dell’Art tradition, dating back to the Italian Renaissance. Their masked faces peep out at us, eager to attract our attention. Their bodies are flat interlocking planes of solid colors: bright white, orangy red, pale green, dark blues, gray, and light brown hues against a chocolate brown background in the New York version and grassy patterned green background in the Philadelphia version. All six figures seem to exude a bit of rambunctiousness. The push-pull of the colors that share parts of their interconnected bodies produces a rhythmic quality. These guys are rockin’. The Pierrots are tooting away on clarinets or Spanish tenoras. The New York Harlequin strums a guitar, while the New York monk sings. The Philadelphia Harlequin pauses from fiddling his violin, bow in his left hand, as his neighbor, the other monk, holds his cup in his right hand and the concertina on his lap with the left. In this MoMA room they are showing off their manly skills to impress six scantily-dress ladies preoccupied with drawing water from a spout.

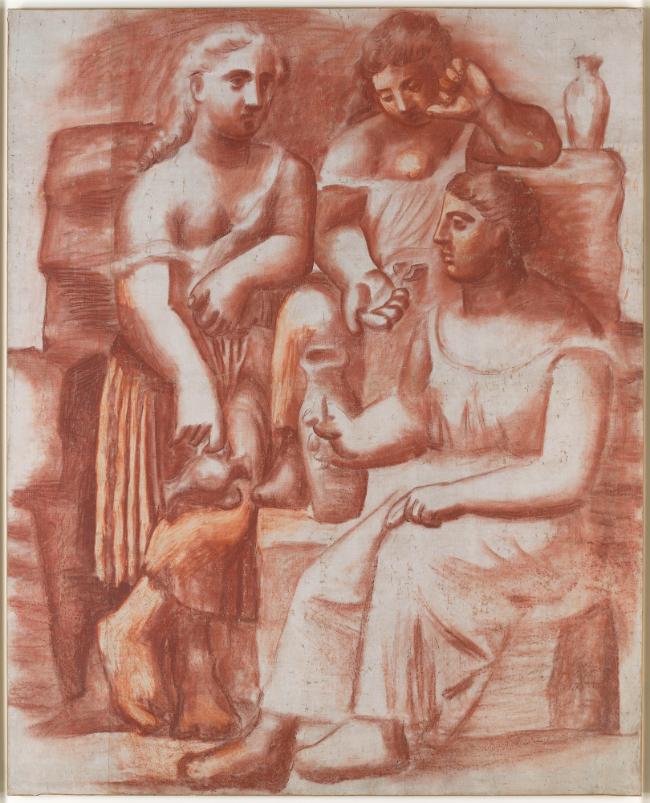

Pablo Picasso, Three Women at the Spring, 1921, Red chalk on canvas. Musée National Picasso-Paris. Dation Pablo Picasso ©2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

None of the Women seem to be listening to these hardworking Musicians. They are lost in conversation, too absorbed in their task and themselves to pay attention to anyone else, including us, their audience. In comparison to Three Musicians, Picasso’s Three Women at a Spring imposes a somber note among the jazzy razzle-dazzle of their male companions. Quiet and contained within their earthy umber background, these colossal bodies, dressed in grayish-white chitons, seem more like 5th century BC Greek columns than lithe ancient Greek sculptures from the same era. They are zoftig and majestic, similar to figures in 17th-century French Classicist Nicolas Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego, which Picasso must have studied in the Louvre. Picasso’s 20th-century version of classical female figures whisper while their male counterparts, six Musicians in this gallery, bray. The women own their space with timeless, monumental stability: salt of the earth, instead of fearsome femme fatales. The musicians seem to represent an ephemeral reality, the fairytale land of theatrical performance.

Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia Ego, second version, 1628, Musée du Louvre. Public Domain

In short, we register an agon here between the flimsy “cubiçant” guys and the substantial “classical” gals reunited in this physical space but perpetually at odds with each other psychologically as they act out two different modes of human interaction. They’re Picasso’s Kens and Barbies – the Great Divide between the sexes. Nothing has changed since these huge canvases left Picasso’s Fontainebleau garage over a century ago. The four groups of only men or women still huddle on the sidelines during this Big Dance of life.

Pablo Picasso, Studies, 1920-1922. Oil on canvas Musée National Picasso–Paris. Dation Pablo Picasso ©2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

Also, these works offer some insight into Picasso’s incipient midlife crisis, caught between his old bohemian life with his Montmartre buddies and his new embourgeoisement with demanding wife Olga and irresistibly adorable Paolo. The late great art historian Theodore Reff interpreted the tres amigos as a wistful backward glance toward Picasso’s early days in Paris when Picasso’s Gang met every day in Montmartre or Montparnasse. This analysis sounds quite convincing since Picasso would turn 40 in October, a significant age for most, usually a time to reevaluate past accomplishments and worry about the ultimate retirement in the not-too-distant future. Death, by the way, is definitely present in Three Musicians. Here’s the scoop on that interpretation.

Installation view of Picasso in Fontainebleau, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 8, 2023-February 17, 2024. Photo: Jonanthan Dorato

In both versions of Three Musicians, we see Harlequin (a ne’er do well ladies man), Pierrot (a sad-sack clown), and a monk. Theodore Reff believed each character alluded to Picasso and two members of his famous entourage: Picasso as his alter-ego Harlequin, the poet/novelist/critic Guillaume Apollinaire as Pierrot, and poet/critic/artist Max Jacob as the monk. In the MoMA version we see parts of a dog under Pierrot’s chair on the extreme left. This Anubis-like creature symbolizes death. Apollinaire died from “Spanish Flu” on November 9, 1918. That summer of 1921, Max Jacob retreated to a Benedictine monastery in St. Benoit-sur-Loire, hence the brown triangle (“hood”) atop a brown rectangle with depicted rope belt in the Philadelphia version and without a belt in the MoMA version.

Installation view of Picasso in Fontainebleau, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 8, 2023-February 17, 2024. Photo: Jonanthan Dorato

Other things to notice: Pierrot wears his signature white clown outfit and Harlequin wears his signature diamond pattern jumpsuit. Significantly, the colors for this Harlequin’s pattern are red and yellow, the colors of the Spanish flag, which reference Picasso’s nationality. Also in both works the figures wear masks and the clothes are reminiscence of the costumes and sets Picasso designed for the Ballets Russe production of Pulcinello in 1920. We imagine these figures are performing on stage as we stand in the front row. We also notice that in the Philadelphia version Pierrot’s clarinet contains a human profile, perhaps a direct reference to Apollinaire.

Cover photo of Annie Cohen-Solal’s book

Annie Cohen-Solal’s book and exhibition A Foreigner Called Picasso points out that Picasso’s identification with Harlequin references his sense of alienation. Harlequin is a stock character in Commedia dell’Arte, whose antics come from the position of an outsider, perhaps a drifter. He causes trouble with his mischievous schemes. He may be The Fool in the Tarot card deck. His character seduces Pierrot’s wife, Columbina, behind Pierrot’s back, which adds sexiness to Harlequin’s attributes, and melancholy to Pierrot’s. No doubt Picasso identified with this flattering aspect of Harlequin, the irrepressible tombeur (ladies’ man).

Installation view of Picasso in Fontainebleau, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 8, 2023-February 17, 2024. Photo: Jonanthan Dorato

Picasso’s late Cubist vocabulary continues the artist’s collage aided planar vocabulary developed during the so-called Synthetic Period of Cubism (1912-14) and connects these paintings to his studio in the Bateau Lavoir, where he created his harlequin paintings during his Rose Period (1905-1906) and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907, the masterpiece that introduced his future Cubist planarity, passage, and geometricity.

From my perspective, Three Musicians, painted together in one studio, might represent his Parisian tertulia, who shared his jokes and pranks, which he performed in his Synthetic Cubist’ collages. These visual and linguistic puns were decoded for us in Elizabeth Cowling and Emily Braun’s illuminating exhibition Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, another contribution to the Picasso 1973-2023: Fiftieth Anniversary celebration.

Three Women at the Spring, on the other hand, continues Picasso’s neoclassical “Ingres Period” with its emphasis on sculptural expression. This exploration of volumetric forms seems to chisel out the face, body, massive hands, columnar pleats, and blocks of stone arranged around the standing and sitting figures. We can see the same classical robustness in Picasso’s Studies (1920-1922) and other portraits of his ballerina wife Olga Khoklova, whom he married on July 12, 1918.

Installation view of Picasso in Fontainebleau, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 8, 2023-February 17, 2024. Photo: Jonanthan Dorato

Picasso’s pivot to a mannered classicism began in 1914 with his unfinished (?) painting, The Painter and the Model. The following year he delicately drew in pencil several Ingres-esque portraits of his friends and dealers, including Apollinaire and Max Jacob. He hadn’t abandoned Cubism, he simply added to his arsenal of visual expressions that seemed appropriate for his state of mind and spirit (son esprit). In 1915, his eerily smiling Cubist Harlequin, also in MoMA’s collection and included in this exhibition, seems to mark his transition from a life with his beloved Eva Gouel (his muse during the Cubist years) and without. She died in December 1915. This period of her illness (cancer or tuberculosis) caused this normally resilient artist much anxiety (described his letter to Gertrude Stein at the time).

Installation view of Picasso in Fontainebleau, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 8, 2023-February 17, 2024. Photo: Jonanthan Dorato

In a 1923 interview Picasso explained: “If an artist varies his mode of expression this only means that he has changed his manner of thinking, and in changing, it might be for the better or for the worse. The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered an evolution, or as steps toward an unknown ideal of painting. All I have ever made was made for the present and with the hope that it always remains in the present.” (Picasso on Art, edited by Dore Ashton, Da Capo Press, 1972, p. 5)

Anne Umland observed: “these four imposing works lie at the heart of Picasso in Fontainebleau, which delves into a strikingly contradiction-filled moment when Picasso seemed intent on demonstrating how in his art, and in his conception of the tradition of painting more broadly, classicism and cubism, the academy and the avant-garde, the historical past and the contemporary present, were dialectically related and inexorably linked.”

Olga Khokhlova in Picasso’s studio, Montrouge, Spring 1918. Photographer: Pablo Picasso or Emil Delatang

This phrase “dialectically related and inexorably linked” holds the key to our appreciation of this extraordinary artistic endeavor. Rarely, if ever, do we see an artist work simultaneously in two distinctly different and contradictory styles, one flat and the other in illusory three-dimensions. Picasso clearly mastered each style at this point in his career but had also reached a crossroads that needed processing before achieving some resolution. When Marie-Thérèse Walter entered his life in January 1927, Picasso seemed to have found his synthesis, allegedly motivated by this blonde, athletic teenager. That may or may not be true, but we can’t help notice Picasso changed his style and dog (according to Dora Maar) every time he changed his mistress. The next Picasso period blends his Cubist criteria with his curvaceous figurative classicism to form his signature “Surrealist” style, perhaps his most iconic visual expression when we think of the word “Picasso” as a noun, an adjective, and a brand.

The conundrum of Picasso’s four Fontainebleau masterpieces created side-by-side in his modest garage-studio may have met its match in MoMA’s ambitious exhibition. Or, it may remain elusive, as much of Picasso’s work continues to be. Although 50 years have passed since Picasso’s death on April 8, 1973 and 122 years have passed since Picasso’s first exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery on the rue Lafitte in June 1901, the protean complexity of Picasso never ceases to challenge and amaze. He was, and remains, one of greatest artists who graced this planet. And we have not heard the last word on his Fontainebleau period, nor any other period, guaranteed.

For more information about MoMA’s Three Women at a Spring, please watch this video, and their Three Musicians, please watch this video. Both videos recount the histories of paintings as physical objects. Fascinating!

The catalogue for Picasso in Fontainebleau, featuring 15 essays, 239 color illustrations is available through MoMA and other booksellers online.

The author also referenced Theodore Reff’s “Picasso’s Three Musicians: Maskers, Artists and Friends,” Art in America, December 1980, pp. 125-142.

Lead photo credit : Pablo Picasso, Spanish, 1881–1973 Three Musicians, Fontainebleau, summer 1921 Oil on canvas 6' 7" x 7' 3 3/4" (200.7 x 222.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund ©2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

More in artists in Paris, Fontainebleau, French artists, history, picasso

REPLY

REPLY