Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

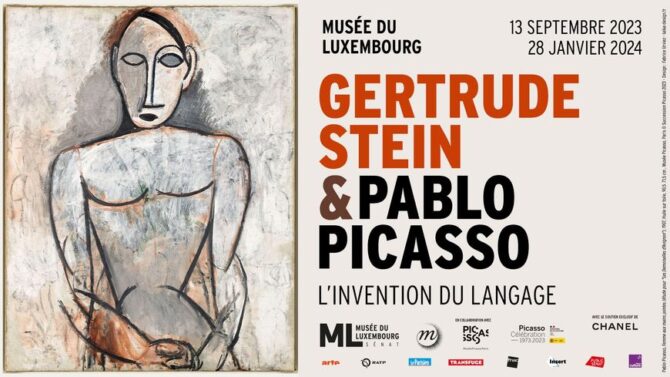

The exhibition currently running at the Musée du Luxembourg is a reminder of the connections between two of the most innovative foreigners who alighted in Paris in the early 20th century. Its title, The Invention of Language, underlines the fact that both Pablo Picasso and Gertrude Stein were breaking new ground. Their long friendship was a key factor in the creative buzz which enlivened Paris from the earliest 1900s.

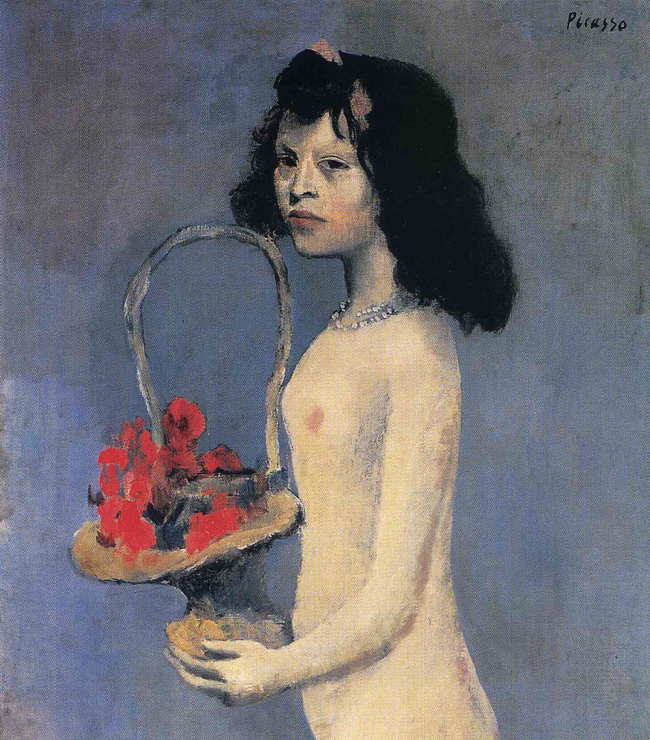

Gertude Stein arrived from the U.S. in 1903 and settled into an apartment in the Rue Fleurus in the 6th arrondissement. Independently wealthy, she spent her time on art, visiting exhibitions at the nearby Musée du Luxembourg and trawling markets to buy pieces by newer artists. When an impoverished Picasso moved to Paris in 1904, he too began mixing in artistic circles, so it wasn’t long until they met. Gertrude’s purchase of his painting “Young Girl with a Flower Basket” in 1905 marked the beginning of the period when his fortunes began to turn. She admired the bold picture of a young flower-seller, depicted nude apart from her ribbons and flowers and in due course she became his most enthusiastic patron.

“Young Girl with a Flower Basket” (1905) painting, Pablo Picasso. Credit: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

The friendship between a wealthy Jew and an impoverished Spanish Catholic, six or seven years her junior (he was only 24) may sound unlikely. But they also had some important things in common, being foreign, newly arrived in the city and eager to make connections in the Paris art world. Gertrude later wrote in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas that she and Picasso “immediately understood each other,” and despite both speaking less-than-perfect French they were soon exchanging ideas on art and feeding off each other.

In the winter of 1905, Picasso asked Stein to sit for a portrait and so began her regular visits to his workshop at the Bateau Lavoir in Montmartre. The commission was another step on Picasso’s journey to recognition, for Gertrude was becoming an influential member of the Paris art establishment and the picture would hang in her apartment among works by well-known painters and be seen by the many visitors she invited to join her to discuss art. Some commented that the piece did not resemble its subject very exactly, but Gertrude herself approved, remarking – in her inimitable style! – that “for me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me, which is always I.”

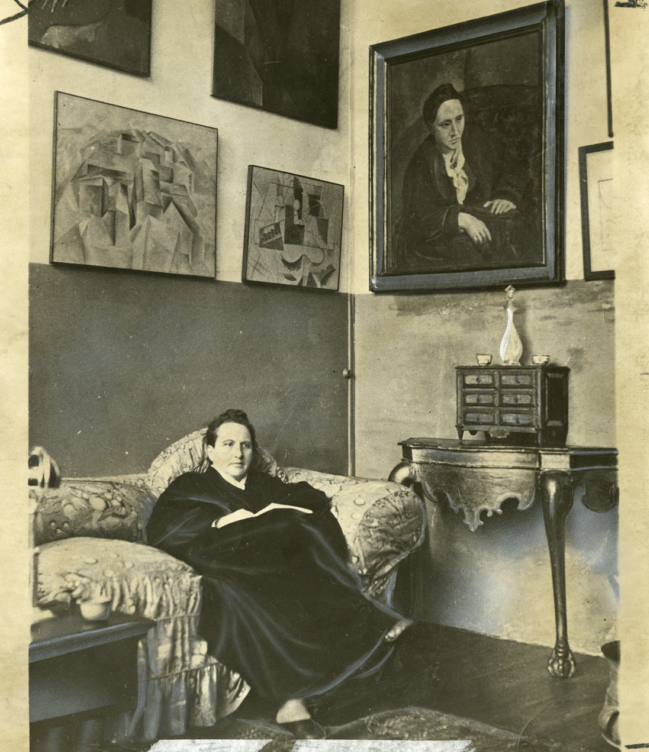

Portrait of Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso inside Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Wikimedia commons

The portrait played an important part in their story. As their friendship deepened, Picasso began accompanying Gertrude home on Saturday evenings and staying for dinner. Gradually this evolved into the weekly salons which Gertrude and her life companion Alice Toklas hosted. Other artists they had befriended came to admire and be inspired by their growing collection of paintings which included works by Renoir, Matisse and Cézanne and to engage in lively debate about the fast-developing modernist movement. It would not be an exaggeration to say that it was here, at 27 Rue de Fleurus, that the avant-garde movement first flourished.

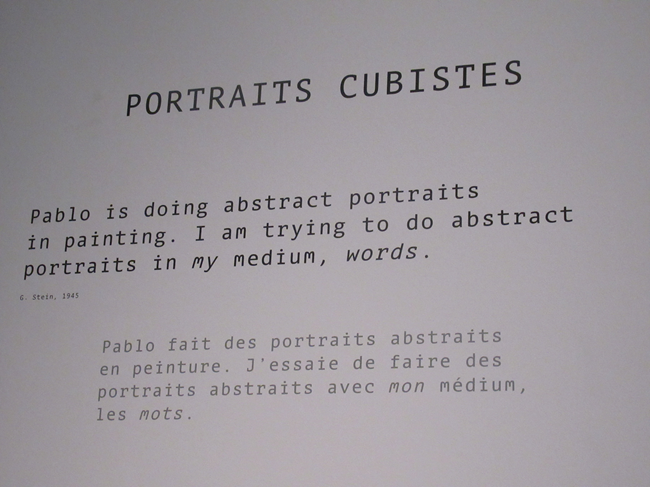

Although each worked in their own medium, there were similarities in their approach. As Stein explained, “Pablo is doing abstract portraits in painting, I am trying to do abstract portraits in my medium, words.” In Picasso’s groundbreaking pieces, Stein found much to which she could relate. The figures he painted were distorted, human bodies were presented in an angular, fractured form. It was all very new and quite shocking to many and, fearing adverse reactions, Picasso declined to show some of his work to a wide audience. His “Demoiselles d’Avignon”, for example, was completed in 1907, but not shown in public for nearly a decade.

Stein in her Paris studio, with a portrait of her by Pablo Picasso, and other modern art paintings hanging on the wall (before 1910). Public domain.

When they first met, Gertrude was writing The Making of Americans. It was an innovative work, nearly 1,000 pages of experimental prose, much of it breaking all the usual rules of grammar and relying on repetitions and enigmatic phrases. One critic labelled her style “cubist,” and a publisher willing to take it on was not found until 10 years after its completion. Another work, Tender Buttons, a collection of prose poems, was lambasted for its “wilful obscurity,” and one critic complained it was “evident that Gertrude Stein had abandoned the intelligible altogether.”

Stein quote at the museum exhibition. Photo Credit: Marian Jones

A short quotation from Tender Buttons illustrates the way her sentences presented words in new and unexpected ways, not unlike the images in a work by Picasso. She wrote: “A Carafe, that is a blind glass. A kind in glass and a cousin, a spectacle and nothing strange and an arrangement system in painting.” Stein found a bigger audience with later works, such as The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, but much of her writing did not have mass appeal. Both she and Picasso were pushing the boundaries of their respective media, subverting conventions and experimenting. They delighted, as Gertrude put it, in creating a reality “in which nothing was where it should be.”

There is no doubt that there was much each admired in the other. Picasso sometimes addressed Gertrude affectionately as “Madame Stein, Man of letters,” and in the 1930s she wrote touchingly of their relationship, using the third person: “I wish I could convey something of the simple affection and confidence with which he always pronounced her name, and with which she always said, “Pablo”. In all their long friendship, with its sometimes-troubled moments and its complications, this has never changed.” As she hints, despite their close friendship, some things came between them.

Study for Demoiselles dAvignon, featured at the exhibition. Photo Credit: Marian Jones

The salon members dispersed during the First World War and during the 1920s there was a new focus on authors, as Gertrude and Alice welcomed expatriate writers from Hemingway’s Lost Generation. But it was really their different approaches to politics and ideology in the 1930s and during the German Occupation of France which had the biggest impact. Picasso was known to oppose the Vichy régime, which made life difficult for him, whereas the fact that Gertrude managed, as a Jewish lesbian, to remain in France and keep her art collection intact is attributed at least in part to her friendship with known collaborators like Bernard Faÿ, director of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Whatever their differences, Stein and Picasso were close for decades and Cécile Debray, curator of the exhibition running at the Luxembourg until January 28th, says that her aim is to explore both their friendship and what she refers to as “their artistic complicity around cubism.” Leading on from that – and referenced in the title of the exhibition, The Invention of Language – comes an interest in the influence both artists had on subsequent generations.

It is really an exhibition in two halves. The opening exhibits, the “Paris Moment,” introduce their work through quotations and pictures which illustrate the startling newness both strove to explore. They include some of Picasso’s cubist pictures, and quotations from Stein’s work. Their relationship is hinted at, for example in a photograph of Gertrude taken by Man Ray in 1922 which shows Gertrude sitting below the portrait Picasso painted of her. Sadly, the portrait itself has not made the journey to Paris from its home at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A Sentence in 5 Colors. Photo Credit: Marian Jones

The exhibition’s second half, entitled “American Moment,” is devoted to works from later periods which continue the idea of a “new language,” in literature and art, but also in other media. Clips of performances mingle with avant-garde artworks. Snippets of text are quoted or incorporated into artworks. Extracts from testimonials are displayed. Here you can peruse, to name just a few exhibits, a video of Merce Cunningham’s post-modern dance from the 1960s, a neon sign which reads “A sentence in five colors,” a recording of music by John Cage and a bank of clocks with short quotations on them, such as Jennifer Smith’s “Is it later yet?” and Gertrude Stein’s “Make it a mistake.”

Clock with Stein quote. Photo Credit: Marian Jones

The exhibition is drawn together at the end by Andy Warhol’s 1980 work, “Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century,” including the Marx Brothers, Einstein and Gertrude Stein herself, all brightly portrayed like pop icons. Both Stein and Picasso were born in the 19th century and their impact spread widely from the early 1900s onwards. Part of their legacy is their continuing influence on later generations of artists. This final, color-popping picture of one by the other is a reminder that both always strove to move art forward, to extend boundaries in search of the new and the different.

DETAILS

Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso: The Invention of Language

Musée du Luxembourg, Paris

Until January 28th

Open every day from 10:30 AM– 7 PM (Mondays until 10 PM)

Entry 14€, 16-25s 10€, Under 16s free

10 Portraits of Jews, Andy Warhol. Exhibition Photo Credit: Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso, exhibition poster

More in Art, exhibition, picasso

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY