Madame Renoir: Who Was the Wife of the Great Artist?

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

A pretty woman is making kissy faces with a little terrier in Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party. This is Aline Charigot, the woman the Impressionist painter shared his life with. Charigot modeled for Renoir over the period from 1880 to 1915. Aline Charigot worked as a dressmaker in Montmartre before becoming Renoir’s lover and the mother of his three children. Pierre and Jean Renoir both went on to have distinguished careers in film, and the third, Claude, became a ceramic artist. Later in life, Aline cared for Renoir as he became increasingly disabled, but she left Renoir a widower for his last four years.

Renoir is well known, but who was his wife? Aline Victorine Charigot was born in the spring of 1859. Her family cultivated grapes in the little town of Essoyes, close to the wine regions of Burgundy and Champagne. Aline was raised by aunts and uncles from both sides of her family, since her parents ostensibly abandoned her. Her father ran away to North America when Aline was a baby, and in turn, her deserted mother moved to Montmartre where she supported herself as a seamstress. Aline was taught by the Sisters of Providence in Essoyes at age 13 but she is known to have received very little formal education.

Young Woman reading an illustrated Journal, 1880. Auguste Renoir

At the age of 15, Aline reunited with her mother in Montmartre. Like Madame Charigot, she was adept at dressmaking, and sewed for a tailor whose workrooms were at the foot of Montmartre, making copies of haute couture dresses for the shops in the rue de la Paix. She earned a good living and shared her wages with her mother.

Aline’s mother made a close friend called Camille, another woman from Burgundy, who owned a crèmerie on Rue Saint-Georges. The crèmerie sold the usual cream, milk, and butter, but Madame Camille also had a side room where customers could enjoy a plat du jour. Aline and her mother were regulars.

Aline was a pretty girl, comfortably plump, with strawberry blonde hair, a retroussé nose and a healthy appetite. Although Aline was known to be a hard worker and very talented, Madame Camille thought she’d be better off finding a good man to marry. Camille was a widow with two daughters of her own to marry off.

Portrait of Madame Renoir, 1885 By Pierre Auguste Renoir

She hoped one of her daughters would marry the handsome Auguste Renoir, a painter whose studio was just across the road. He was often found warming himself up inside Madame Camille’s café. With his foxy looks, smiling face, and happy disposition, he was very appealing to the women of Montmartre. Despite this attention, Madame Camille thought Renoir helpless and hopeless when it came to finding a wife and pushing 40, he wasn’t getting any younger.

According to Jean Renoir’s biography of his father, Madame Camille said that Renoir “…is so thin it wrings your heart. He should have a wife.” But Renoir already had his heart set on another habituée of the little restaurant, Aline – and Aline was already smitten with Renoir.

Oarsmen at Chatou, 1879 By Pierre-Auguste Renoir – National Gallery of Art. Wikimedia Commons

Aline began posing for Renoir on her days off from work. One of her first modeling jobs was Renoir’s 1879 painting, Oarsmen at Chatou. She loved the perpetual holiday feel of the Île de Chatou. She enjoyed rowing and was continually out on the Seine. Renoir taught her how to swim – first holding on to a lifebuoy, then a rope – but Aline quickly learned to swim like a fish.

Two of Renoir’s other models tried to polish the country girl up a bit, but Aline resisted – she didn’t want to be a faux Parisian. Renoir loved her rich Burgundian accent and the way she rolled her Rs. He also loved her looks, her naturalness, and her unpretentious fondness for food.

Entrance to the Maison Fournaise on the banks of the Seine. Photo credit: Moonik / Wikimedia commons

La Maison Fournaise restaurant on the Île de Chatou was one of her favorite places to go with Auguste. At the Maison Fournaise there was always dancing to the accompaniment of a jolly piano. Aline danced better than her boyfriend Auguste. Renoir said her step was so light that she could walk on the grass without hurting it. It is here at the Maison Fournaise, that Aline is pictured with a small dog and a large cast of Renoir’s friends in his most famous painting, the Luncheon of the Boating Party.

Luncheon of the Boating Party by Auguste Renoir

Aline was Renoir’s ideal. Because she fell within Renoir’s exacting parameters of what his models should look like, he’d unwittingly been painting her likeness for years. Their son Jean described how his father was attracted to a “cat” type of woman, with almond-shaped eyes, a kittenish tip-tilted nose and high cheekbones, all of which Aline possessed. There were times when Renoir put down his palette and gaze at her instead – why improve upon perfection? She, on the other hand, loved watching her boyfriend paint.

Renoir was unsure he could provide for Aline and her wish for a family. Renoir was growing anxious about his work. The Luncheon of the Boating Party had taken 16 difficult months to complete. To him, it represented the end of Impressionism. Sensibly, Aline knew that painting was Renoir’s raison d’etre. Caring not if he was successful, she suggested that to save money they live simply in her home town of Essoyes. Madame Charigot threw up a roadblock. She didn’t want to lose her talented daughter or her share of Aline’s pay packet. For Renoir it was a retrograde step, he needed to be inspired by Paris.

Frustrated and peeved, Aline returned to her employer and resumed her life as a single woman. She took steps to avoid Renoir in the midst of his 19th-century mid-life crisis. In 1881 Renoir began a period of traveling, first to Algiers, then onto Spain.

Portrait of Renoir by Frédéric Bazille (1867). Montpellier, Musée Fabre.

While Renoir was away in North Africa, Aline was considering an invitation from her father to join him in Canada. Victor Charigot, who at that time was living in Winnipeg, had written to her in August of 1880, urging her to come to Canada, where he asserted she would earn more money than she made in Paris. Back in 1860, Aline was only 15 months old when her father disappeared. He eventually settled in North Dakota after starting out in Canada. He was a bigamist, and had two children, step-siblings whom Aline never met.

The usually decisive Aline couldn’t make up her mind. Renoir knew about Victor’s letter and told her, “Write to me before you leave. I’ll only be a way for a month, but heaven knows when you’ll be back.” She didn’t make the hard trek to Canada. It was probably the best decision she made.

While Renoir was abroad, he decided his life was incomplete without Aline. He wrote copious letters to her, one of which told her he was returning to France. She was waiting for him at the station. They settled together in his studio in the rue Saint-Georges (see Google Street View below) and from that moment, they were together for the rest of their lives. Well, almost.

In October 1881 Renoir and Aline visited Italy where he studied the work of Raphael, Tiepolo and Veronese. Aline called it their “honeymoon,” yet they were not legally married for another nine years. Most of Renoir’s colleagues were unaware that he had romantic entanglements of any sort. Why did Renoir play his cards so close to his chest? Was the sly Renoir still playing the field? Probably, yes. The Montmartroises still swarmed around the amiable, handsome Renoir.

When Renoir returned from Italy, he began a series of paintings with the exquisite Suzanne Valadon as his model. Valadon’s looks fit right in with Renoir’s roster of models and he employed her several times. She was adept at self-promotion, and Valadon claimed that Renoir succumbed to her charms. She accompanied him to Guernsey, allegedly to model. In the autumn of 1883, word came that Aline was fast approaching the Channel Island. Renoir beseeched Suzanne Valadon to instantly pack up and leave.

Valadon is the model for both Renoir’s Dance at Bougival and Dance in the City. She posed for the third in the series, but rumors of an affair so incensed Renoir’s Aline, that, in a pique of jealousy, she had Renoir scrape Valadon’s painted face off the canvas and entreated Renoir to replace it with her own.

If Aline was to stay with Renoir, she wanted to start a family. She gave birth to their first son, Pierre, in 1885 when Renoir was 44. The new family moved to a more spacious apartment in rue Houdon. Still devoted, the couple married five years later in the mairie of Paris’s 9th arrondissement on April 14, 1890.

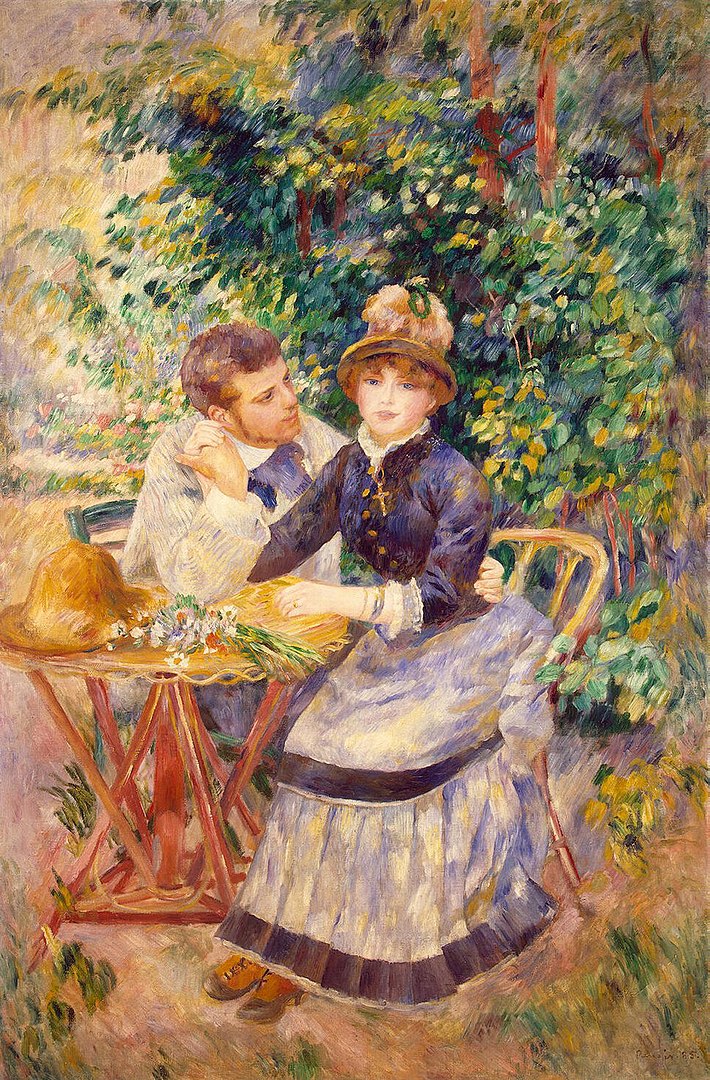

In the Garden, 1885. Pierre Auguste Renoir

In September of the same year, Renoir and his family moved into a wing of the Château des Brouillards at 13 rue Giradon in Montmartre, where Renoir set up a studio in the attic. Today the house is largely hidden from sight on the Place Casadesus, and is located closely between the Moulin de la Galette (which Renoir famously painted in 1876) and Renoir’s former lodgings at what is now the Musée de Montmartre on Rue Cortot. The large house boasted a garden overgrown with flowers and distant views into the countryside. Jean Renoir, who was born at the chateau, remembered it as “a little paradise of lilacs and roses.”

courtesy of Musée de Montmartre

A third son Claude was born in 1901. Aline created a convivial buzz around Renoir that as a bachelor he wasn’t used to. There was always something going on. She raised their children, and as they grew wealthier, she supervised their various nannies and maids, and their little dog Qui Qui. Renoir’s models were frequent visitors that needed to be kept in line. Aline became famous among his artist friends for her culinary skills, particularly for her bouillabaisse. Grilled herrings with mustard sauce was another of her husband’s favorites. On Saturday nights she made a traditional Saturday night pot au feu. Everyone knew the Renoir’s door was open – no need for invitations.

Maternity or Child at the Breast, 1885. Pierre Auguste Renoir

As Renoir’s career became more lucrative, Aline’s dream of living a comfortable life in her hometown of Essoyes came true. From 1888 they summered there; their stays lingered from weeks into months and ended up buying a house in Essoyes in 1896. Renoir grew to love the town. He relished in the local produce and the generosity of the winegrowers. Local villagers and the surrounding landscapes were his fresh subjects. Again, family, friends and models followed the Renoirs out into the country.

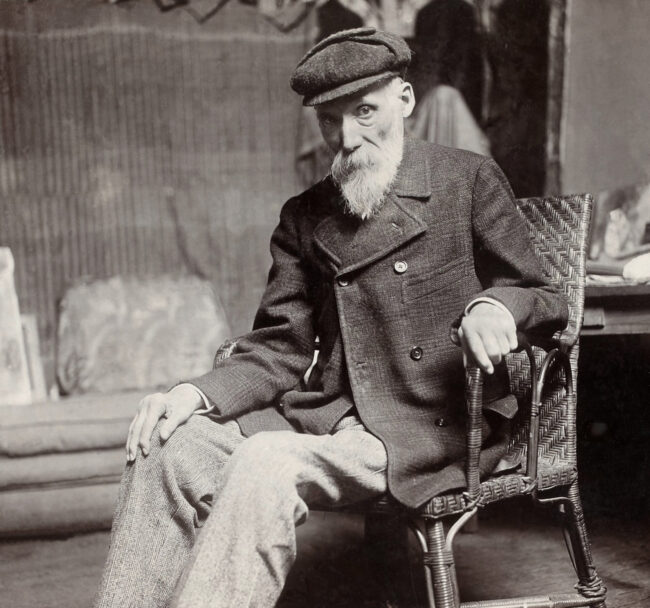

Renoir photographed by Dornac in 1910. Public domain

In 1903, they moved further south to Cagnes-sur-Mer, building their new house, Les Collettes. The weather in this Provençal region helped Renoir’s aching bones. When Renoir’s arthritis became severe, Aline organized everything, even the washing of her husband’s paintbrushes and artfully arranging flowers in earthenware pots so her husband could have a posy to paint. She created a paradise on earth for her wheelchair-bound husband to replicate. Aline supervised the planting of fruit trees behind the house, as well as redolent, pines and eucalyptus. Beds of colorful irises maintained the Les Collettes’ ethereal look. She festooned the house with vines that yielded good eating grapes. She cultivated herbs and vegetables at the bottom of the garden. New dogs Zaza and Bob worked their way onto Renoir’s canvases.

As Aline aged she became very stout and practically lived in her dressing gown. The doctor informed her she was a diabetic. Insulin wasn’t yet used as a treatment, and Aline knew her days were numbered. She refrained from telling Renoir just how bad her situation was.

Madame Renoir and Bob. 1910. Auguste Renoir.

Their sons Pierre and Jean were both injured in World War I; Jean badly so. Aline hurried to his bedside. When Jean was out of danger, Aline returned to Cagnes and died of a heart attack on 27 June 1915, aged just 56.

Aline was buried in the south of France but her remains were later moved to Essoyes. A monument based on Renoir’s 1885 painting of Aline nursing their first child overlooks her grave.

Essoyes/ Aube Office of Tourism

Lead photo credit : Renoir 1880 Madame Renoir with a Dog By Auguste Renoir from Wikimedia Commons

More in Aline Charigot, artists, Madame Renoir, painting, Renoir