Passion for the Pot-au-Feu, the Meal and the Movie

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The words pot-au-feu, or “pot on the fire”, conjure up a simmering kettle of meat and vegetables suspended over a fire. It was once considered commonplace, but for many this rustic dish is the symbol of traditional French cuisine.

The term derived from the pot itself – a cauldron, or earthenware vessel – that peasant wives kept simmering on the hearth. It was a humble dish, started in the morning when ingredients would be tossed in the pot, covered with water and left to cook slowly for several hours. The ingredients used for the pot-au-feu depended on what livestock the family reared. Centuries ago, paysans had to make do with fatty off-cuts of pork and stringy chicken. Root vegetables – carrots, parsnips, turnips, celeriac and onions – stored for the winter, were part of the stew. Depending on the region and the time of year, cabbage, leeks, and cauliflower could be included. A peasant farmer would consume most of the meat and vegetables for his midday lunch. The thick broth that remained bubbled away over the fire until it could be sopped up with bread for the evening meal.

Léonard Jarraud, Le pot-au-feu (27 x 17,8 cm). Musée d’Angoulême, Charente (France).

The officious Dictionnaire de l’Académie française says the term pot-au-feu was coined in the 17th-century, yet the first instance, spelled pot au fu, was recorded in medieval times. However, similar stews would have been prepared centuries before. In 1792, the phrase “pot-au-feu” was first evidenced in the English language as a term for a large cooking pot.

Incidentally, it was also in 1792 that Goethe stopped to sample this typically French dish, while he was crossing the volatile Lorraine region. Here’s what Goethe said about his experience.

“The beef was almost already cooked when carrots, turnips, leeks, cabbage and other vegetables were added. The servant placed small slices of good bread into the plates and bowls set on the table. She then poured the bouillon from the kettle and bid us to eat it. The meat and vegetables completed this very simple dinner, which seemed to please everybody.”

Thus, in the late 1700s, the plain-old- pot-au-feu had found social status; other well-to-do foreigners sought it out.

Pot-au-feu. Photo credit: Andre/ Wikimedia commons

Over time, pot-au-feu has embodied French egalité with perhaps a soupcon of fraternité. Available to all, it honored the tables of rich and poor alike. Communal, it was ideal for sharing amongst family and neighbors. Economical, because like the stone soup and nail broth of fables, its richness depended on what was added to the pot. Choice cuts and famous chefs elevated the unpretentious pot-au-feu into haute cuisine. To have such a proletarian meal in the mouths of peasants and princes seems like the democratization of dining.

The pot-au-feu went out of fashion for the general populace during the French Revolution and Napoleon’s rule, when meat became more expensive for the lower classes. Under King Louis Philippe (1830-48), a working-class diet depended upon the staples of meat, cheese and soup. On Sundays, scraps of meat would be added to the daily pottage. For commoners, pot-au-feu was no longer a common dish. The expanding Parisian bourgeoisie could afford better cuts of meat, and the dish fell under the purview of the middle class. Nevertheless, classic French cuisine was nothing more than provincial cooking gone to town.

Joséphine Baker during a distributio of pot-au-feu in 1932. Photo credit: Agence de presse Mondial Photo-Presse / BNF/ public domain

In the 1800s, the dish had become so prevalent with the middle classes that everyone had an opinion. Just about any French writer with a quill described the once-modest meal. Food influencer Brillat-Savarin mentions pot-au-feu in his Physiologie du Gout (the Physiology of Taste), describing a mysterious osmazome, emanating from the cooking process of the pot-au-feu. Now obsolete, the word osmazome referred to a sort of seductive, juicy ‘essence of meat,’ giving the dish its characteristic flavour and aroma. Today the closest word we use would be umami, meaning a pleasant, savory taste.

Emile Zola and Guy de Maupassant described the simplicity and substantiality of pot-au-feu in their respective books, L’Assomoir and La Parure. George Sand remembered her impoverished mother toiling over the fire and saw the pot-au-feu as a symbol of the traditional values which Sand felt were being eaten away. Flaubert’s Le Château des Cœurs (1863) contains a fantasy, set in the “Kingdom of the Pot-au-feu”- a realm symbolizing the bourgeoisie. The pot characterized the conservative tenets they held dear. Their vaunted cauldron swelled until it blotted out the sun, a parable for conformity over the individual. For some reason McDonald’s springs to mind!

Pot-au-feu became so central in the French diet that the founder of grande cuisine, Marie-Antoine Carême, used the pot-au-feu as the first recipe in his tome L’Art de la cuisine française (1833-34). Carême’s opening paragraphs acknowledged the significance of the pot-au-feu to France itself. He described it as the domain of the woman, although his preamble, peppered with snippets of chemistry, and the repetitive references to osmazone seems aimed at those toqued men who dominated haute cuisine. A typical 19th-century housewife would be left out in the cold.

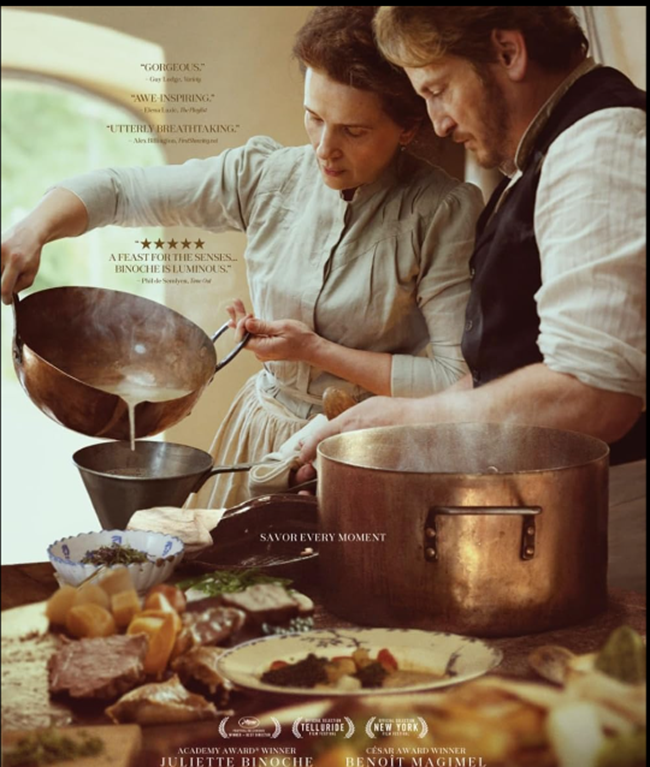

La Passion de Dodin Bouffant (The Taste of Things) film, starring Juliette Binoche and Benoît Magimel

Had the fictional epicure Dodin-Bouffant lived and breathed, he would have rubbed shoulders with the likes of Carême and Escoffier. In the story The Life and Passion of Dodin-Bouffant, by Marcel Rouff, the chef-de-cuisine offers up an honest taste of the French terroir to the Prince of Eurasia. The recipe included in Rouff’s book was so authentic, real-life chefs often prepared it. Now there is an award-winning film, directed by Tran Han Hung, which tells the story of Dodin-Bouffant (played by Benoît Magimel) and his long-standing cook Eugénie (Juliette Binoche). Originally titled The Passion of Dodin-Bouffant, this gorgeous foodie film was very cleverly renamed Pot-Au-Feu. The pot-au-feu is featured, but the movie’s focus is the duo’s love for each other, which, like the savory stew, has long-simmered. For English speakers it has been renamed the rather insipid The Taste of Things.

Personally, the most concise pot-au-feu recipe is from Elisabeth Luard’s book, Family Life: Birth, Death and the Whole Damn Thing.

Here is my take, with some very subtle changes.

Pot-Au-Feu Recipe

- 2lbs/1kg beef, bone in, (flat or short rib or chuck roast)

- 2lbs/1kg boneless beef shanks

- 2 or 3 short lengths of marrowbone

- 6 pints /3.5 liters water

- 2 onions unpeeled and halved

- 1-2 large carrots, scrubbed and roughly chopped

- 2-3 celery stalks

- A tied bouquet garni consisting of a bay leaf, sprig of thyme, parsley stems

- ½ tsp peppercorns

- Salt to taste.

Finishing vegetables.

- 2-3 carrots scraped and roughly chopped

- 2-3 potatoes peeled and roughly chopped

- 2-3 leeks, well-washed and roughly chopped.

- ½ cabbage cut into thick slices.

- Put the meat and the bones in a large pot with the water. Bring to a boil. Skim off the grey foam that rises. Add the rest of the ingredients. Bring back to the boil. Turn the heat right down, loosely cover and allow to simmer quietly for 3-4 hours until the meats are tender.

- Remove the meats and the marrowbones and reserve. Discard the soggy vegetables. – They’ve done their part.

- Bring the broth back to the boil and add the fresh carrots and potatoes. Turn back down to a simmer. After 10 minutes, add the leeks and lay the cabbage on the top. Cover loosely for another 10 minutes until the vegetables are tender.

- Slice the meats and reheat in the broth. Add the marrowbones. Or spread the marrow on a bit of toast.

- Dish up and serve in deep plates. Accompany with bread to sop up the juices.

Pot-au-feu dans son bouillon. Photo Credit: akosma/ Wikimedia Commons

There are as many versions of pot-au-feu as there are chefs. Julia Child and her collaborators on Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle, recommended beef, pork, chicken and sausage, and added an onion studded with cloves. Alain Ducasse says beef and beef only. Paul Bocuse used beef, veal and chicken. Anthony Bourdain threw in an ox-tail and veal. He like Julia’s onion/clove bomb too. You can’t go wrong with root vegetables. Carrots and onions are agreed on by everyone. British food pioneer Elizabeth David balked at the very idea of cabbage.

Pot-au-feu at Le Louis Philippe in 2023. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

Over the decades the popularity of the pot-au-feu has withstood the vagaries of the economy. Living standards improved dramatically after the mid-20th century. Most French households could afford to buy meat more regularly and a family pot-au-feu was a Sunday evening staple. The pot-au-feu has been refined over generations to represent what is wholesome and unpretentious about traditional French cuisine. The late Anthony Bourdain called it “soul-food for socialists.”

Pot-au-Feu is served at hundreds of restaurants throughout Paris. I first encountered it at Le Louis Philippe, as a chalkboard special. The server advised us to finish the marrow or he wouldn’t remove our plates! Bon appétit!

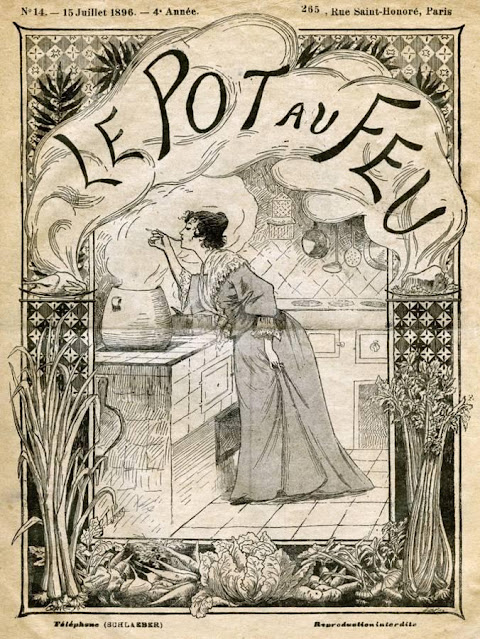

Front cover of “le-pot-au-feu”, 15th July 1896

Lead photo credit : "La Passion de Dodin Bouffant," starring Juliette Binoche and Benoît Magimel

More in French food, Pot au feu