Paris Noir at the Centre Pompidou

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Paris Noir, showing until June 30th at the Centre Pompidou, is an exhibition which thinks big, for it is showcasing the work of 150 artists over the half century 1950 to 2000. They are linked by their Black roots, which explains the Noir of the title, but the Paris is equally significant. A major theme is the role the city has played in the development of Black art, not just in Europe, but across Africa and the Americas. It’s a story of inspiration and cross-fertilization, a tale where history, art and politics intermingle.

Paris Noir features mainly works of art – paintings, photographs, collages, sculptures, film and more – which have not been shown in France before, the aim being to “illuminate” the work of artists “who have been eclipsed.” A two-hour visit is recommended and in fact I was there a little longer, keen to absorb as many as possible of the thought-provoking ideas and influences jostling for attention.

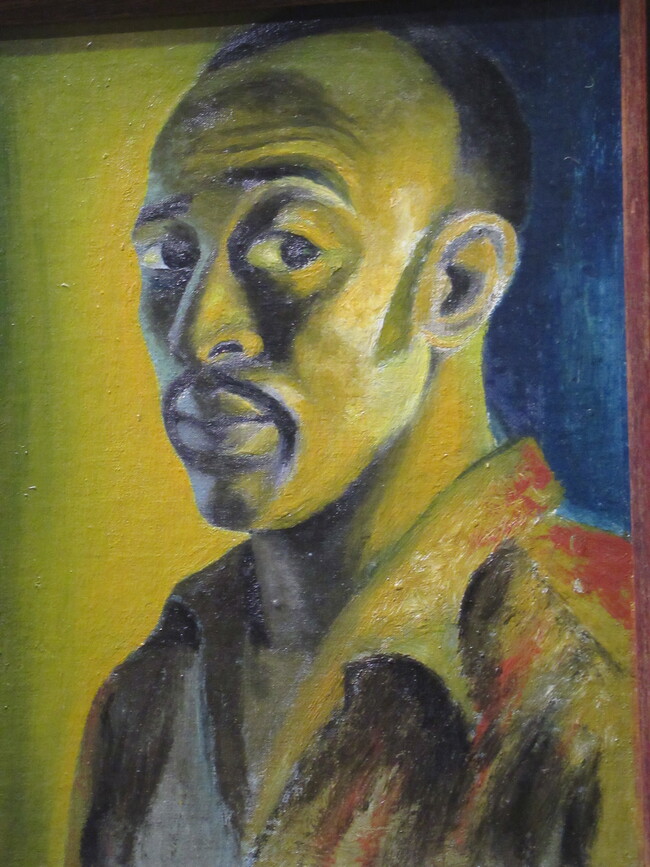

Gerard Sekoto self portrait. Photo at the Centre Pompidou exhibit: Marian Jones

The poster for the exhibition features a self-portrait by the South African artist Gerard Sekoto, painted in 1947, just days before he chose to leave his homeland for political exile. His departure was just a year before the apartheid regime began and his uneasy stare, fixing a point beyond the viewer, portrays his anxiety. He made Paris his new home, initially eking out a living as a jazz pianist while trying to further his artistic career. While every story is different, Sekoto represents many of the featured artists who sought artistic refuge in Paris, then found themselves battling difficult conditions.

The first section of the exhibition, Pan-African Paris, sets the scene just after World War II when increasing numbers of Africans were arriving in Paris. Some, like Gerard Sekoto, came seeking refuge, many more were students from France’s colonial empire who had been awarded scholarships to study in Paris. They were drawn to the area around the Sorbonne in the city’s Latin Quarter, where the jazz clubs and cafes served as meeting places where new arrivals from so many different countries could mix. One place, above all, was instrumental in helping African culture take root in Paris, namely Présence Africaine.

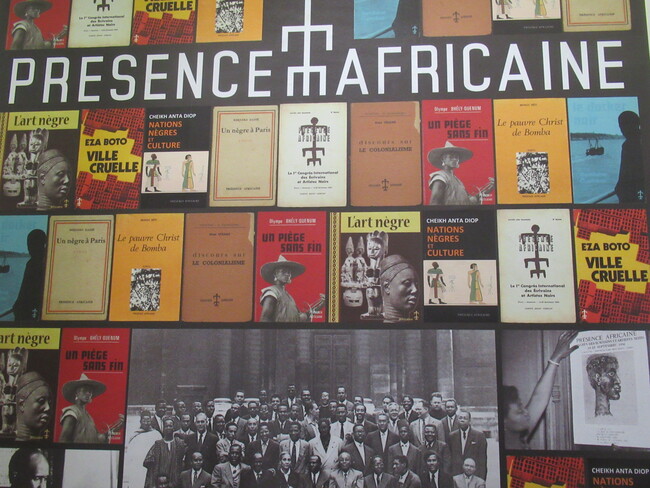

Presence Africaine. Photo at the Centre Pompidou exhibit: Marian Jones

Initially a magazine, then a bookshop and publishing house, Présence Africaine was founded by the Sengalese writer Alioune Diop in 1947 as a way of promoting African culture. A montage prominently displayed here indicates the breadth of interests covered, ranging from books on art and culture – l’Art nègre (Black Art) for instance – to key political works such as Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism. It was a hub for new ideas from the African continent, a place where a lively mix of influences from many different lands could be celebrated.

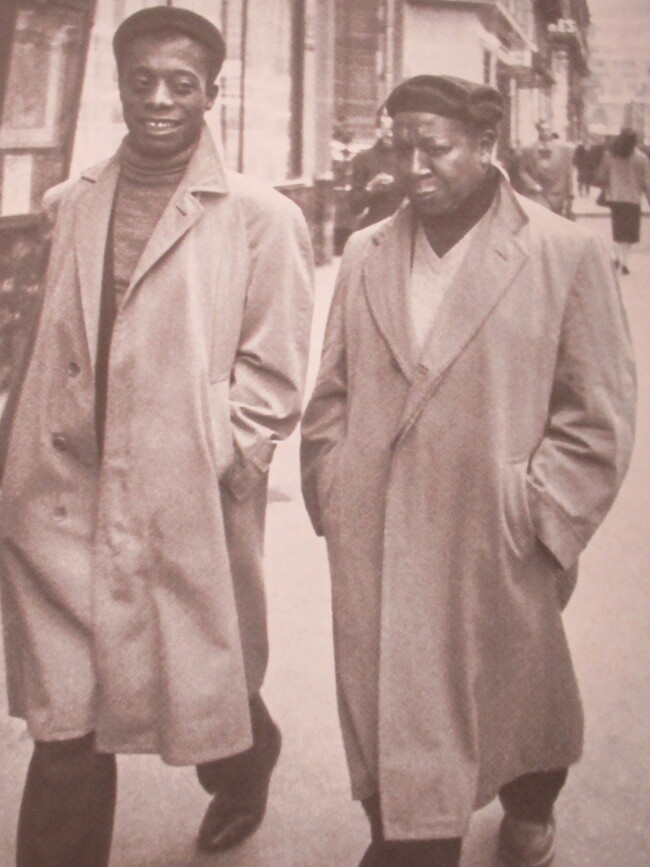

A second major dimension to Black culture in post-war Paris is illustrated by a photograph of two African American friends James Baldwin and Beauford Delaney, taken in a Paris street in about 1960. Many Black Americans came to Paris from the 1950s, often seeking a freedom which they could not find living under segregation in the U.S. Their story is also one of artistic endeavor mixed with political involvement, exemplified by James Baldwin, well-known as a novelist, essayist and playwright and also an influential voice in the Civil Rights movement.

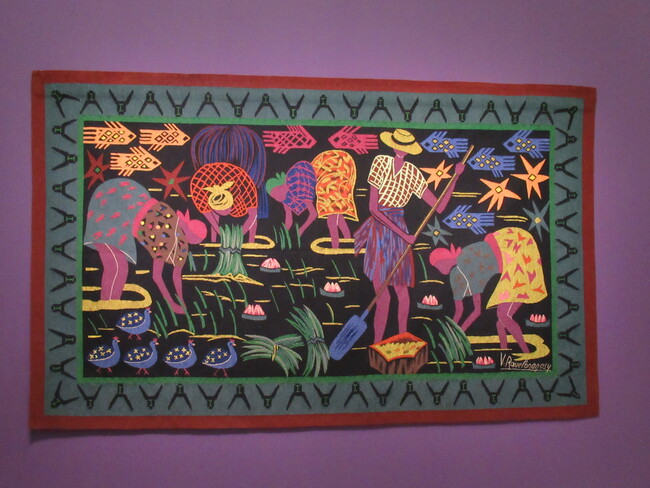

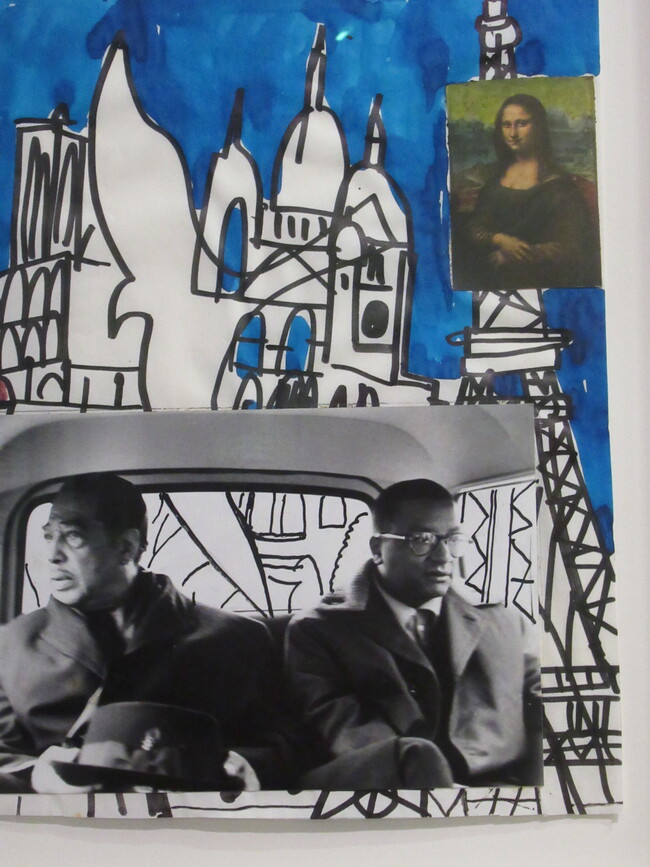

Subsequent sections highlight a whole range of links and cross-fertilizations. Some works, such as Victoire Ravelonanasy’s Le Repiquage du Riz à Madagascar (Transplanting Rice in Madagascar) bring the colors and culture of Africa bursting into Paris. Others take more obviously French topics and give them a new slant, such as the Sacré Coeur piece by Romare Bearden from his Paris Blues/Jazz series. A collage, it shows a photograph of musicians Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn driving a car against a backdrop of such Parisian emblems as Sacré Coeur and the Mona Lisa. The whole series celebrates the jazz scene in Paris which drew so heavily on both American and European cultures.

Another aspect is highlighted by the work of artists like Diagne Chanel, born in the 1950s to a French mother and Senegalese father. The first inspiration for her striking work, Le garçon de Venise (The Boy from Venice) was her interest in Italian Renaissance art and she describes the painting’s Venetian backdrop as “very classical and western.” In the foreground she painted an African figure, modeled by a student she met at the National School of Decorative Arts in Paris. She describes the result as “an artistic punch,” explaining that it was important to her, “as a mixed-race person born in Paris,” to create a work which blended both the cultures in her background.

A number of the African artists who came to Paris went on to play decisive roles in the development of art on the African continent, something which is highlighted in the exhibition’s section entitled “Paris-Dakar-Lagos.” Several were instrumental in the World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, held in 1966, for example. The Senegalese artist Iba N’Diaye, who had studied architecture and fine arts in Paris, where he also worked with the Russian-French sculptor Ossip Zadkine, created the Dakar School of Fine Arts, the first art school in an African country. He designed the teaching program to encompass art and art history from both African and European perspectives.

Another interesting development is described in the section entitled “Back to Africa.” In the 1960s and ’70s a number of Black Caribbean artists who had studied in Paris became interested in researching their African roots. Two artists from Martinique went to the Ivory Coast where they founded the Negro-Caribbean School of Art in the city of Abidjan. The Vohou-Vohou movement which came out of this then found its way back to Paris. So, out of the mixing of artists from so many cultures in Paris came influences which traveled to and fro across three different continents.

Sacré-Cœur by Romare Beardon. Photographed at the exhibition by Marian Jones

The themes of independence and the fight for social justice are another common link. The French colonies of Ivory Coast, Senegal and Madagascar gained their independence in 1960, when the Civil Rights movement was at its height in the United States, yet in France, Africans and African Americans were sometimes facing discrimination. The prominent African American writer James Baldwin, who had left the U.S. for Paris in 1948, drew a parallel when he said “the Black man in the U.S. is the Algerian in France.” The Haitian artist Roland Dorcely, who spent much of the 1950s and ’60s in Paris, described the negative reactions he encountered when taking his work round Paris galleries: “I have to admit that only one out of three dealers even bothered to look at my canvases. They expected a guy in a loincloth, with a bow and arrow, not an admirer of Winslow Homer and Seurat.”

In the section entitled “Revolutionary Solidarities,” photographs of Black activists taking part in demonstrations in Paris such as Halte au racisme are displayed next to protest pieces such as Iba N’Daiye’s haunting ink drawing, Le droit à la parole (The right to speak). Also included is Beauford Delaney’s portrait of the African American contralto Marian Anderson. She had made her debut at the Paris Opera House in 1935 and was, by the 1960s, a respected civil rights campaigner, promoting such causes as the Congress of Racial Equality. Delaney’s vibrant portrait of a woman held in such high regard that she sang at the inaugurations of both Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy shines a light on the battle for equality.

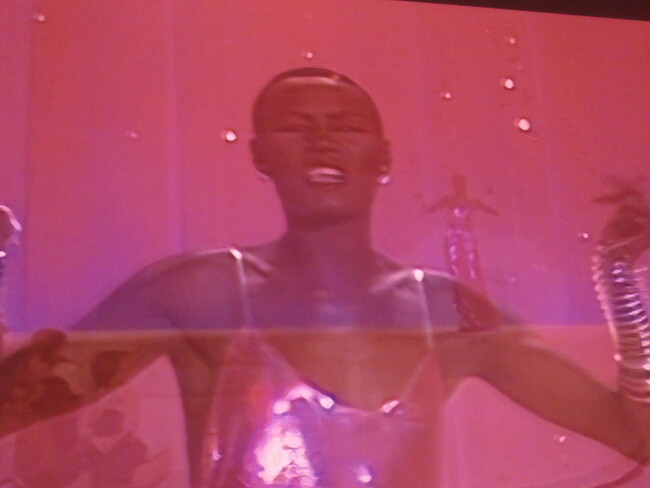

The last sections take the many-stranded story of Paris Noir into the later decades of the 20th century: film footage of Grace Jones singing La vie en rose; a link between two seismic events which were marking their bicentennial, namely the French Revolution and the end of French colonial rule and slavery in Haiti; the founding of the influential Revue Noire in the 1990s, a cultural publication aimed at further strengthening the ties between France and Africa.

The Centre Pompidou will close this summer for a five-year renovation. That is surely a reason to visit if you can, especially as it will allow you to see Paris Noir, to experience lots of new-to-France artworks and to understand a little better the rich cultural tapestry woven around Paris and its Black artistic heritage. But allow plenty of time – it’s a multilayered topic with much to ponder.

DETAILS

Paris Noir

At the Centre Pompidou until June 30th, 2025

11 am – 9 pm

Closed on Tuesdays

Late night opening until 11 pm on Thursdays

Entry 17€, Concessions €14

Grace Jones, La vie en rose – on film. Photographed at the exhibition by Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Paris Noir at the Centre Pompidou. Photo: Marian Jones

More in centre pompidou