Americans in Paris, James Baldwin: A Freedom Fighter Without a Home

Even before I was seduced by Hemingway, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec to the inevitability of living in Paris, I had already read Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin.

This small, sparely and simply written book set in 1950s Paris of a love affair between two men, vividly describes not only the emotional torment of each man, but also the underbelly of the seedier bars and clubs in the less salubrious quartiers of la capitale.

I still love the book. It lead me on, of course, to Another Country, Go Tell it on the Mountain, and Nobody Knows my Name.

James Baldwin always believed that Paris had been accepting of both his race and his homosexuality when America had proved too hard a place to make his life.

A passage in Giovanni’s Room (albeit from the view of a white homosexual) depicts the turmoil of a homosexual in the 1950s in his failed attempt to escape his sexuality by moving to Paris.

“There is something so fantastic in the spectacle I now present to myself of having run, so hard, across the ocean even, only to find myself brought up short once more before the bulldog in my own backyard-the yard, in the meantime, having grown smaller and the bulldog bigger.”

Baldwin moved to Paris in 1948. He was born in 1924, the eldest of nine children. His stepfather, David Baldwin, was a preacher and was especially hard on his stepson, with the result that James spent as much time as he could out of the home and studying in libraries. Their home was in Harlem and incidents of racial abuse by the NYPD heavily influenced Baldwin in his writing.

Baldwin was a gifted writer from an early age and was encouraged by teachers who recognized his talent. His stepfather was less impressed and although Baldwin followed him into a religious life– indeed drawing bigger crowds than him from the pulpit– he soon became disenchanted with religion and left the church. His stepfather died when James was 19 which gave him the freedom to make his own decisions, no longer under the influence of his stepfather’s often tyrannical rule.

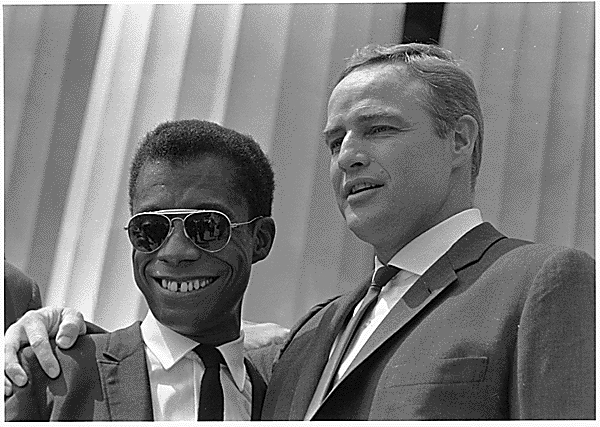

He arrived in Paris with $40, not speaking a word of French. He had however already befriended Richard Wright in Greenwich Village who had helped him gain his first fellowship. (Here for a time he had shared an apartment with Marlon Brando who remained a life-long friend.) A second fellowship enabled his move to France.

Baldwin made straight for Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the beloved haunt and right of passage for so many young American writers before him. He lived in the Rue Verneuil, (Serge Gainsbourg’s home for years), hooking up immediately with Richard Wright in Les Deux Magots on the first night he arrived. (Although there was a famous falling out between the two, Baldwin always acknowledged Wright as the most important black writer in the world.)

Baldwin and Brando. © NARA

Baldwin’s later books and essays were uncompromising and unflinchingly honest about being a black man in America. Although this theme dominated his work, he also wrote with the same brutal honesty about family and sexuality.

Like Hemingway and others before him, Baldwin wrote in the cafés of the Left Bank. Go Tell it on a Mountain was written in the Café de Flore, and the wonderful Art Deco cafe, Le Select in Montparnasse, saw Baldwin studiously writing Giovanni’s Room. These cafés, like Baldwin’s other favorite meeting places, Le Montana on Rue St Benoit, L’Abbaye and Chez Inez on the Rue Champollion, were not the rather bourgeois and expensive establishments we find today, but were slightly decadent, maybe even a touch louche. Baldwin also frequented Les Halles and Pigalle, neither of which had ever attempted respectability…

It was obvious when the Black Civil Rights Movement started in America that Baldwin would be a part of it, making friends with Nina Simone, Harry Belafonte and Lorraine Hansberry. He returned to America in 1957 to be a part of the movement despite equal rights for homosexuals not being part of their agenda. In fact, homosexuality was positively deplored. He was as outspoken verbally as he was in his writing. He was especially critical of Hoover and the FBI. Little wonder then, that FBI files from 1960 to early 1970s show 1884 documents on Baldwin, only 276 on Richard Wright and a mere 110 on Truman Capote.

Baldwin’s essays on police brutality resulted in almost constant harassment. His phone was tapped and disguised FBI agents even followed him abroad through France, Britain and Italy. Any thoughts of making America his permanent home again were gradually eroded and Baldwin always returned to France where he felt most at home and accepted for what and who he was.

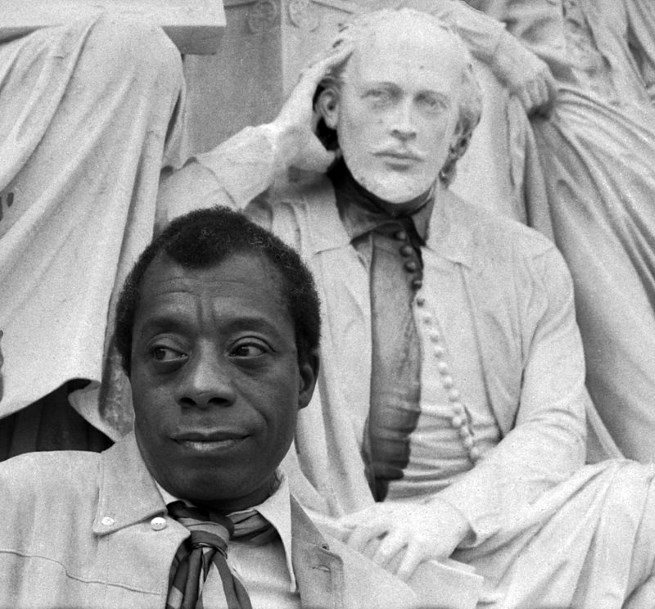

Bladwin with Shakespeare, photo: Allan Warren

His involvement in the Civil Rights Movement brought him into contact with Martin Luther King, but after his assassination and the assassinations of Malcolm X and Medgar Evers, all close friends, Baldwin’s illusions of racial reconciliation were shattered. He nevertheless refused to align himself with the Black Arts Movement, who believed that their literature should be exclusively for black writers and attacked Baldwin for his interracial love affairs and confronting the issues of multi-racial societies in his books and essays.

In 1970, Baldwin with his partner, Bernard Vassell, moved to an old farmhouse in St Paul de Vence. His friends, a diverse group, including Ray Charles (for whom he wrote several songs), Josephine Baker, Sidney Poitier and Yves Montand with his wife, Simone Signoret, were regular visitors.

Baldwin continued to write up until his death of cancer in 1987 and continues to be the most influential and relevant black writer both then and now.

His powers of description, his eye for detail and his ability for the reader to so easily identify with situations or emotions of the characters in his books, still make this passage from Giovanni’s Room one of my most loved. I KNEW this woman– she worked behind the till in Le Conti in the late 1960s. Everyone in Paris who went to a café, knew this woman, but none could have depicted her with the accuracy and humor of James Baldwin.

“Behind the counter sat one of those inimitable and indomitable ladies, produced only in the city of Paris, but produced there in great numbers, who would be as outraged and unsettling in any other city as a mermaid on a mountain-top. All over Paris they sit behind their counters like a mother bird in a nest and brood over the cash-register as though it were an egg. Nothing occurring under the circle of heaven where they sit escapes their eye, if they have ever been surprised by anything, it was only in a dream-a dream they long ceased having. They are neither ill-nor good natured, though they have their days and styles, and they know, in the way, apparently, that other people know when they have to go to the bathroom, everything about everyone who enters their domain. Though some are white-haired and some not, some fat, some thin, some grandmothers and some but lately virgins, they all have exactly the same shrewd, vacant, all registering eye; it is difficult to believe that they ever cried for milk, or looked at the sun; it seems that they must have come into the world hungry for bank notes, and squinting helplessly, unable to focus their eyes until they came to rest on a cash-register.”

If you have never read Giovanni’s Room, read it now and imagine an impoverished black man scribbling away in Le Select in Montparnasse, never imagining the force he was to become in modern day literature.

James Baldwin may have died in his beloved France in St Paul de Vence, but he was buried in Harlem in Ferncliffe Cemetery, Greenburgh, New York.

He had come full circle on a remarkable journey.

Baldwin’s grave in Harlem. photo: Tony Fischer

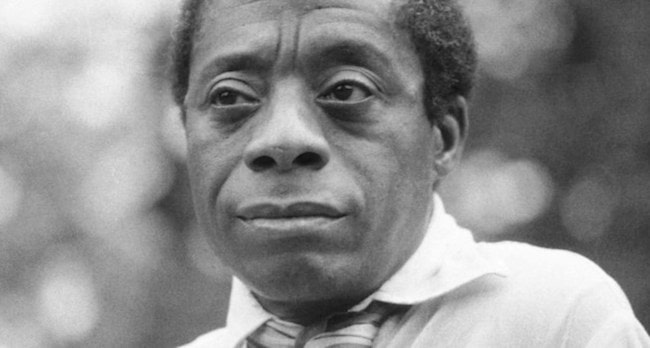

Lead photo credit : James Baldin taken Hyde Park, London 1969. photo: Allan Warren

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY