Jules Chéret: King of Belle Epoque Poster Art

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Before Toulouse-Lautrec there was Jules Chéret. A talented lithographer, he was a master of Belle Epoque poster art, changing the very essence of the medium.

Artists Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha are more well known today, but they owed an immense debt to Chéret’s inventions. (Acknowledging Chéret’s influence, Toulouse-Lautrec sent every poster to him first before anyone else saw it.)

Originally known as broadsides in the 1600s, printed simply in black and white on one side, the posters were a quick and effective way to mass-distribute information. Shopkeepers used them to advertise their products in windows, governments used them to call men to arms, and who can forget the “Wanted Dead Or Alive” posters in the Wild West? Public information such as the “Declaration of Independence,” printed on July 4th, 1776, was pasted on walls throughout the American colonies. These posters were cheap to produce, served their purpose, and were then pasted over or thrown away. But technology moved inexorably onwards, typefaces became a little more eye catching, and decorative images were sometimes added to grab the viewer’s attention.

But it was the reinvention of lithography that changed everything— lithography that turned posters into fine art. And Jules Chéret was the artist responsible for this seismic change in how posters were perceived.

Jules Chéret – Fêtes de Nice 1907 Poster. Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, Wikimedia Commons

Art and innovation

Lithography had been invented in 1798 by Alois Senefelder, a Bavarian playwright and actor, to reproduce his scripts. Lithographs are prints made from inked and greased drawings on a stone surface. A separate stone was required for each color, a laborious task, especially when the stones used were large and extremely heavy. The stones were then pressed with force onto the paper. To add color — a chromolithograph — was so time-consuming, that lithographs remained pretty much black and white, with perhaps the odd splash of color, well into the 1860s.

Chéret worked out a method using only three stones. One inked in red, one in black and one shaded orange-red to blue-green. By making these colors semi-transparent, they could be layered to create different shades. Not content with the endless possibilities of layering colors, Chéret utilized the limestone with an artist’s eye, using animated brush lines, stipple, cross hatch and soft water color-like washes. He designed his own lettering, so that the text across a drawing became part of the overall design. Lithographs had never been beautiful before and the effects were astonishing. Chéret’s creativity and ingenuity transformed the world of advertising overnight, and turned lithography into a recognized, respectable, sophisticated and saleable art form.

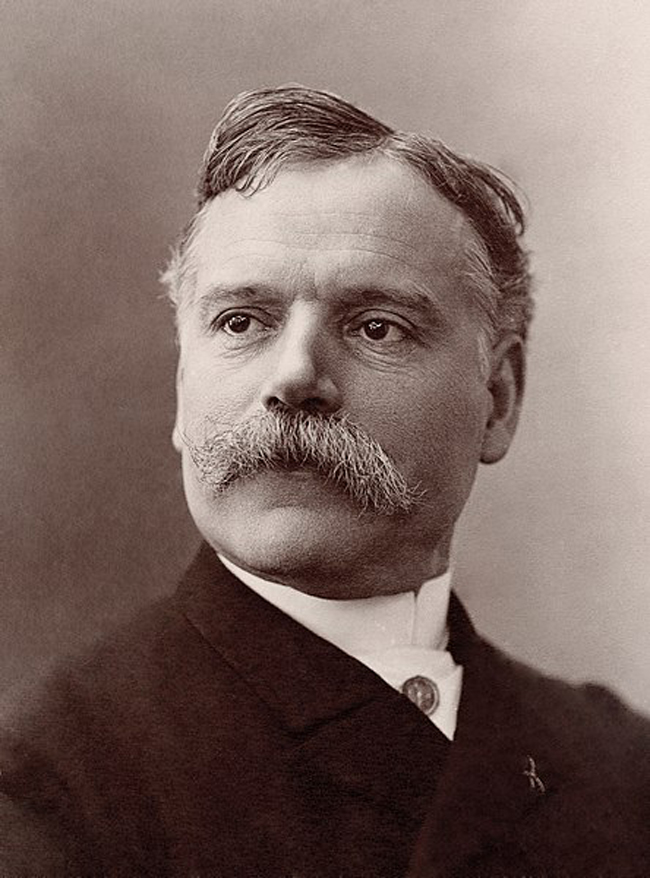

Alois Senefelder (1771–1834), inventor of lithography. Public Domain

Chéret was born in Paris in 1836 into a family of poor, but creative artisans. His education was limited, and at 13 years of age, he began a three-year apprenticeship with a lithographer. He was already interested in painting, immersing himself in the Paris art galleries while studying at the École Nationale de Dessin. He moved to London in 1859 to study lithography and stayed there for seven years before returning to Paris in 1866, his head bursting with new ideas which came into fruition in the late 1860s. Eugène Rimmel, a businessman and perfume manufacturer, hired Chéret as a designer. But Chéret was so convinced of the future of his method of lithography, that he started his own firm in Paris — alongside two brothers, Léon and Alfred Choubrac. The lithographs weren’t just groundbreaking, they were also cheaper to produce thanks to new technical methods. By 1877, Chéret was running a large workshop with steam-powered lithograph presses which allowed him to supply the high demand from both collectors and businesses for their advertising.

Skyrocketing popularity

For Chéret’s posters had been an instant success. Parisians adored them, and for the first-time posters became a consumer product. Avid collectors followed bill stickers, bribing them for a new poster before it was pasted on the wall. In fact, the posters became so sought after, that a law was passed in Paris that created official posting places, to prevent the city being smothered with them.

The vibrant colors, pretty (often sexy) women, and joyful movement in theses posters brightened up a grey, urban commute and added another dimension of interest to a daily walk through the quartier. This was accessible art. Art on a public wall, art outside in the open air, art that was free to look at, not in a gallery. Art that could be displayed and enjoyed on street furniture that had been designed specifically for posters. Advertising was now an art form. Officially, lithographs were now art.

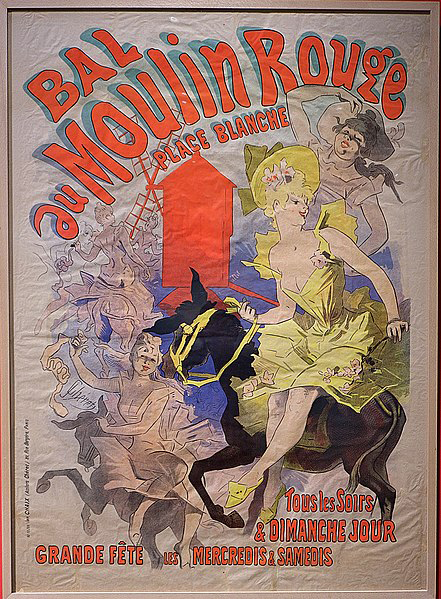

Baile del Moulin Rouge, Jules Chéret, 1892, Wikimedia Commons

While most people would recognize a Toulouse-Lautrec poster in a second, Chéret’s name has not seemed to linger on in the public’s memory in the same way— despite his fame in Paris where he produced more than a thousand posters. Today his posters still resonate. Everyone has seen one even if they cannot identify the artist. “Yvette Guilbert, Au Concert Parisien” (1891) could easily be mistaken for a work by Toulouse-Lautrec. Likewise, “Théâtrophone (Theater phone)” (1890) has the hallmarks of Impressionist paintings: the sharp-featured woman, top-hatted man with distinctive mustache, and the shadowy figures in the background.

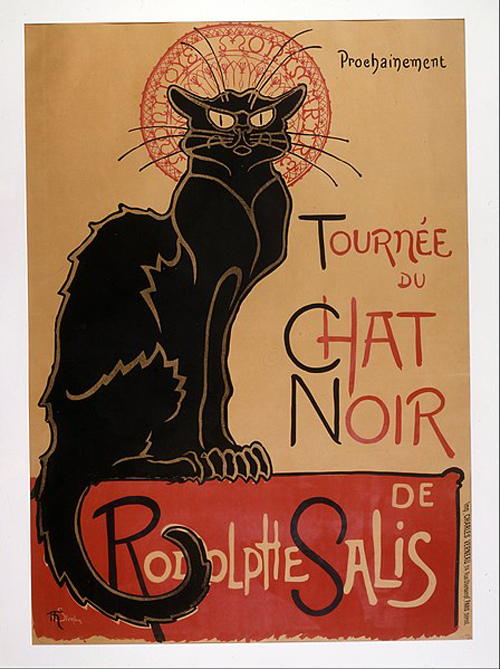

You are probably familiar with “Tournée du Chat noir,” one of the most iconic posters of the 19th century. This was produced by Théophile Steinlen, who followed Chéret’s method of lithography.

Théophile Steinlen: Tournée du Chat noir, 1896. Public Domain

Frivolity and freedom

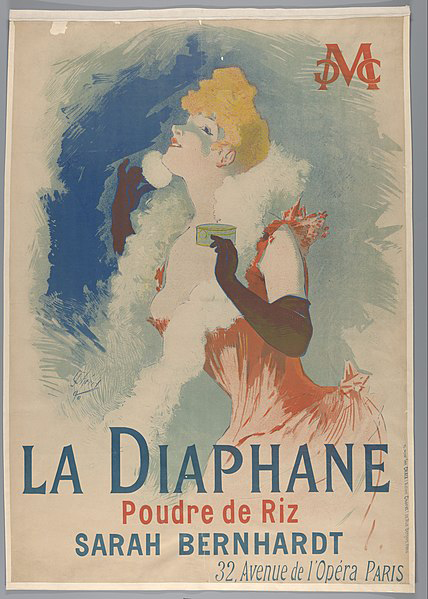

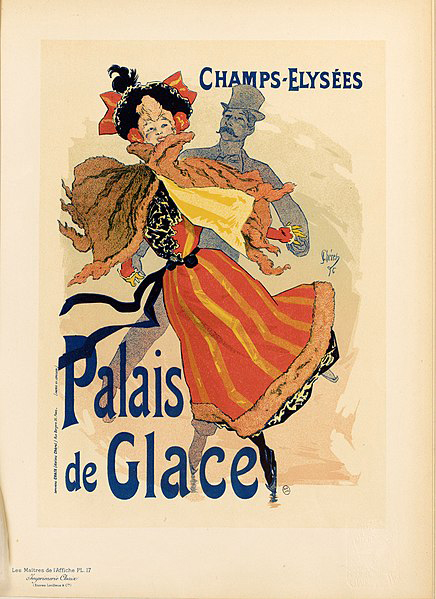

The advertising posters for the Palais de Glace and Taverne Olympia are typically Chéret with the subjects depicted as jolly, effervescent, enjoying themselves. Two advertisements for Pétrole de sûreté — “L’Aureole du Midi” and “Saxoleine”— are striking in their use of exaggerated movement. Some of these lithographs were huge; “Saxoleine” measured over 91 inches by 32 inches. Cheret acknowledged that his posters were influenced by scenes of frivolity in the works of Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Antoine Watteau— the perfect style for advertising department store goods, cosmetics and soaps. Sarah Bernhardt was the poster girl for “La diaphane, poudre de riz.” (This vintage poster sold for $4,000 in 2021.) But Chéret tackled alcohol, beverages, petrol and oil advertising posters with the same enthusiasm for vibrant colors and vigor.

La Diaphane. Poudre de Riz ,1890. Public Domain

In his depictions of music halls such as the Olympia, he showed light and joyfulness, dispelling any dark, salubrious connotations that women in such venues were apt to evoke. Whether dancing half-clad or advertising perfume, hair dye or bicycles, Chéret’s women are ebullient, cheerful, and free-spirited. And women loved them. There was a form of emancipation for women in the posters; these subjects, colorful and joyous, often smoked and wore low-cut tops. Pasted across Paris, the women in these posters were so popular, they were nicknamed “Chérettes” and Parisian women felt liberated to emulate them.

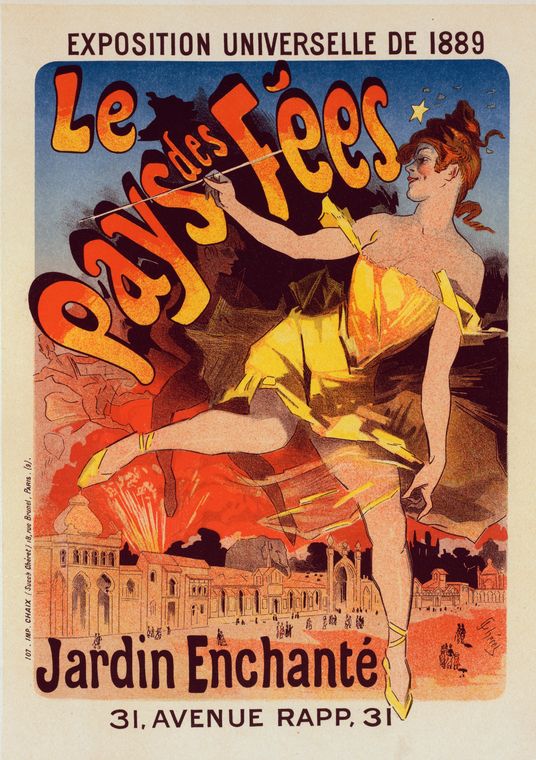

In 1895, Chéret curated Les Maîtres de l’affiche (The Masters of the Poster,) a collection of 256 original Belle Epoque posters in small format. Chéret chose the best work of 97 Parisian artists and he contributed several works of his own art including “Papier à Cigarettes JOB” and “Punch Grassot.” Toulouse Lautrec contributed the “Divan Japonais” and Georges de Feure, the “Salon des Cent/ 31 Rue Bonaparte.” Lesser-known names helped make up an eclectic, international group of contributors: the English artists Julius Price and Dudley Hardy; the American Louis Rhead who contributed “The Sun”; and the Belgian Armand Rassenfosse with his “Grande Brasserie.” The imprimerie Chaix played a significant part in copying Chéret’s vision through printmaking — the print shop that published these smaller chromolithographic versions in authentic colors. These renowned posters, a history in themselves of the Belle Epoque, were each rendered as a single sheet measuring 11 and a quarter inches by 15 inches. Every month for five years, from December 1895 – November 1900, subscribers received a parcel containing four consecutively numbered poster reproductions. The monthly package also contained a bonus plate of a specially created lithograph.

Maîtres de l’affiche V 1 – Pl 17 – Jules Chéret. Public Domain

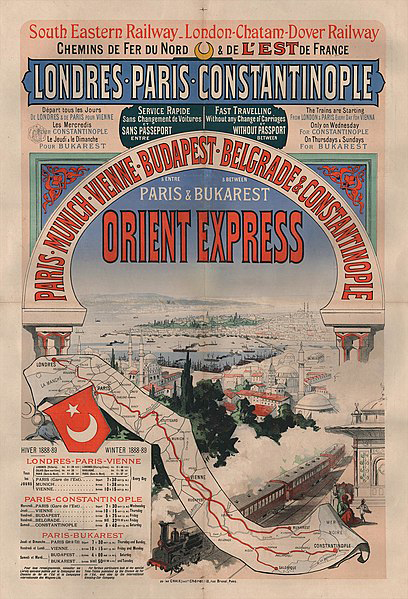

But of course it was the over-sized posters, some more than life-sized, that had caught the imagination of the public. This kind of instant, eye-catching, and accessible advertising seemingly had no limits. Consumers were everywhere, avid for new products, and with the advent of train networks opening up exotic destinations, the travel poster was born. In 1888, the first ever poster of the Orient Express was issued, designed and produced, of course, by Jules Chéret.

The influence of posters on consumers in the 19th century cannot be underestimated. Children began to appear on posters in domestic but attractive surroundings, their toys and clothes becoming instantly desirable. Aspirational consumerism influenced by art. And Jules Chéret was at the heart of it.

Poster advertising the Orient Express, Jules Chéret, 1888. Public Domain

The legacy of a groundbreaking artist

In 1890, Chéret was awarded the Legion d’Honneur for his astounding contribution to the graphic arts. The award recognized him for “creating an art form that meets the needs of Commerce and Industry.”

In old age, Chéret, now a wealthy man, retired to Nice and the warmer climes of the Riviera. A museum was established in his honor there, four years before his death: the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nice. His eyesight failed him in 1925 and he died seven years later at the age of 96. He was buried in the Cimetière Saint-Vincent in the Montmartre quarter of Paris. In 1933, a year after his death, he was honored with a posthumous exhibition of his works at the prestigious Salon d’Automne in Paris.

Cimetière Saint-Vincent, photo @ Francisco Gonzalez

Since Chéret’s sensational depictions of Belle Époque Paris, posters have been unquestionably accepted and embraced as an art form, used worldwide in protest or support, for the latest film, airline, cosmetic or simply propaganda. Poster art is a part of all of our lives — it still remains an art of the people, creating an instant visual impact with its own particular message, saying: Look at Me! If the posters are anywhere near as eye-catching as Cheret’s, we can be sure to do just that.

And this is Jules Chéret’s formidable legacy.

Lead photo credit : Jules Chéret (1836 - 1932), French Poster Maker. Public Domain

More in Jules Chéret, Jules Chéret lithography, Jules Chéret Posters

REPLY

REPLY