The Death of the Paris Metro Ticket

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

I would take a bet that anyone who has visited Paris anytime after 2007 will be able to find lurking — perhaps in an old suitcase, a coat pocket, inside a wallet, or between the pages of a book — a white Paris metro ticket. These iconic cardboard tickets measuring a mere 6.5cm x 3cm are used by 1.6 billion metro users each year. (Before 2007, the colors changed from brown, mauve, yellow and green.) Tickets can be purchased in a “carnet,” a booklet of 10 tickets at a reduced price (16,90 € or a single ticket for 1,90 €). Nevertheless, 500 million single-use tickets are still purchased every year. These tickets are valid not only on the metro but also on buses, trams and the RER in zone one. The tickets’ strip can easily be demagnetized by proximity to keys, coins or mobile phones, but can be exchanged free of charge by staff in the metro ticket booth.

Paris Metro Ticket Machine, Creative Commons

Why so many metro ticket souvenirs? On a commute, a metro ticket was an obvious choice as a bookmark, perhaps before mobile phones took the place of books. They were also a tool in flirtations; their handy size perfect for writing a phone number on. Some metro riders, more dexterous, made tiny frogs out of them. But soon these tickets will be phased out, with vending machines in some 180 stations slated to stop selling carnets of cardboard t+ tickets in mid-October 2022. Throughout 2023, there will be a gradual end of the sale of carnets at all vending machines and ticket offices in the RATP network.

Marilyn Brouwer’s preciously guarded metro ticket with holes punched

The argument for discontinuing their use is environmental: The use of paper cardboard and also the pollution caused by old tickets being dropped on the ground. Many tickets are simply lost or discarded after use, and apparently it takes a year for a metro ticket to decompose. The solution, not always so lauded, is plastic, in the form of the reusable Navigo cards. (In an ironical twist, the paper metro ticket won an unexpected six-month reprieve because of the global shortage of electronic chips used in the replacement Navigo cards.)

Navigo Découverte Card, Wikimedia Commons

Transition to the Navigo Pass

The Navigo pass has gone through several changes since its inception in the early 2000s. Once only Parisian residents were eligible to use it with proof of identity and a photograph. There are still variations of the Navigo Pass, but perhaps the one most suited to tourists is the Navigo Easy Card. The plastic card costs 2 euros and can be loaded with single tickets, 10 packs and day passes. You can reload your Navigo card at any RATP kiosk. For weekly or monthly passes, the Navigo Découverte card is recommended. The card itself costs 5 euros and requires a small photo. Unlike the anonymous Navigo Easy card which can be used by others (although not on the same trip, i.e. it cannot be passed back to a friend at the turnstile,) the Navigo Découverte card cannot be shared.

Prices to date: Weekly pass. 22.80 € (Price per day 3, 26 €) Monthly pass 75,20 €. (Price per day 2,43 €) The card is valid for seven days of travel on all metro, RER, trams and buses.

There is also a Paris Visite pass which comes in 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-day increments. They can be purchased for either central Paris zones 1-3 or zones 1-5 which encompasses, for example, airports, Versailles and Disneyland Paris.

Despite the advantages of a plastic card, stored in your wallet with your credit cards, there is still a deep and abiding love — soon to be nostalgia— for that little piece of white card that is uniquely Parisian.

Disneyland Paris castle, Sean MacEntee Creative Commons

So where did it all start?

We have to go back 120+ years to the very inception of the metro. It was the French engineer Fulgence Bienvenüe who built the Paris metro in 1896. (His name is now immortalized in the metro station Montparnasse Bienvenüe). A busy and multitalented engineer, Bienvenüe improved the drinking water of Paris and built the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. (Ironically, he had a less than propitious relationship with trains; in 1881 at the age of 29, his left arm was amputated after he fell on train tracks.)

Montparnasse – Bienvenüe metro station, Creative Commons

Work began on the metro line 1 in October 1898 and it began operating on July 19th, 1900. The Paris metro beat the New York subway by four years, the NY subway opening in 1904. However the London underground, the first underground railway in the world, beat them both by about 40 years, opening in 1863.

The Paris metro’s launch coincided with the Olympic Games being held in the Bois de Vincennes. Unsurprisingly line 1 ran from Porte Maillot in the west to Porte de Vincennes at the city’s eastern boundary and took only 27 minutes.

Bienvenüe standing at the entrance to Monceau station. Public domain

Some 30,000 tickets were sold on that first day at 15 cents for second class (old currency) and 25 cents for first class. First-class carriages endured until 1991. The seats were leather, but otherwise there was little difference between first and second class, except second-class was far more crowded.

In the same year, the Exposition Universelle ran from 15th April until 12th November. The venues included the Champs de Mars, Trocadero and the Bois de Vincennes. This World’s Fair, emblematic of the Belle Epoch, celebrated major inventions, electricity, cinema and not least, the opening of the Paris metro. Unsurprisingly, the Exposition attracted thousands of foreign visitors, and, within a few months, the metro had attracted some 4 million travelers.

Grand entrance, Exposition Universelle, Paris, France, 1900, Creative Commons

In 1919, the tickets were simply brown paper, soon to be replaced by the same rectangular shaped cardboard as now – only the colors and the price changed over time.

As with the changing colors, the trains themselves changed color from their original wood. Barely three years after the metro started in 1903, a catastrophic fire in one of the wooden carriages standing at Ménilmontant station killed 84 people; 77 died from toxic fumes that had swept through the tunnel to Couronnes station. The disaster did not deter people from using the metro, but an alternative fireproof material was urgently sought for the trains. The answer came in the form of Sprague-Thomson, an American invention of all metal rolling stock. Originally grey, the color changed to yellow and then to the more iconic red and green that was used until 1983.

86-404-P Metro Ticket, Paris, WWI by Naval History and Heritage Command, Creative Commons

In the meantime, the metro had expanded across Paris. Line 4 crossed the Seine in 1910, joining Porte de Clignancourt and Châtelet on the right bank to Raspail and Porte d’Orléans on the left bank. By 1934, the metro had reached the suburbs via line 9, at Pont de Sèvres in Boulogne-Billancourt. There are now 16 metro lines (numbered 1-14, 3bis and 7bis). Line 1 and Line 14 are fully automated. The lines serve 308 stations and 64 transfers between lines. In fact, the Paris metro is second busiest in Europe after Moscow. Châtelet les Halles is one of the largest metro stations in the world boasting five metro and RER lines, and currently under construction are the orbital lines (15, 16, 17 and 18), serving outside the city limits.

(A fun aside: On July 20th, 2004, a certain Geoff Marshall from the UK attempted to break the Guinness Book of World Records by traveling on all 369 subway stations (as there were then) in the least time possible. There were already record holders for the New York subway and the London Underground. He began at Porte Dauphine and ended 14 hours, 54 minutes and 18 seconds at the Préfecture de Créteil. Unfortunately Guinness World Records rejected Geoff’s claim on the basis that there were hundreds of metro railway systems in the world and therefore only New York and London were considered. Geoff’s rebuttal was succinct. London had only 270 stations and New York one less than Paris at 368. Sadly Mr Marshall did not win the argument.)

Porte Dauphine entrance, (Hector Guimard) Creative Commons

Metro memories

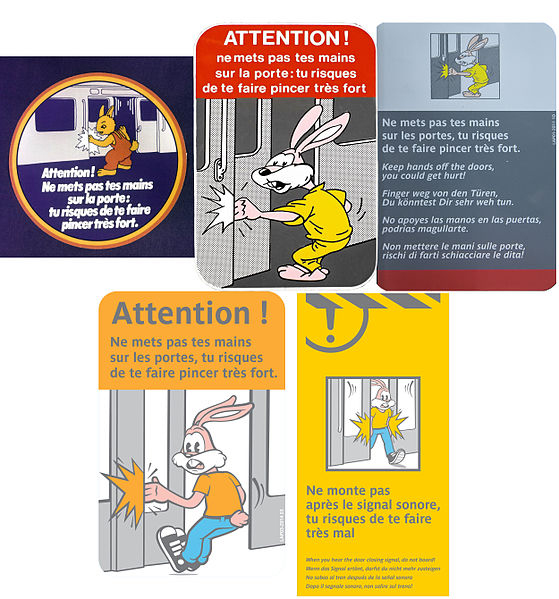

In 1968, payphones were introduced on certain metro lines. Between the noise of the train lines, swaying of the carriages and jostling of passengers, their efficacy was limited. Then there is the iconic “Rabbit of the Metro,” the anthropomorphic rabbit visible on stickers to warn children and older passengers of the danger of getting their hands caught in the carriage doors. As emblematic in Paris as “Mind the Gap” in London.

Evolution of Serge la lapin, Wikimedia Commons

Undoubtedly the most famous and well-loved song concerning the Paris metro — and its oblong cardboard ticket — was written and sung by France’s even more beloved bad boy of pop, Serge Gainsbourg.

“Le poinçonneur des Lilas” is a song about a ticket puncher in the metro, ignored by the passengers, punching holes in tickets all day long, little holes, more little holes, living underground, going crazy and dreaming of the day he will no longer be punching little holes. The French took this song so much to their hearts that if you visit Serge Gainsbourg’s grave in Montparnasse Cemetery, you will find it strewn with metro tickets in homage to him.

I still have a few white metro tickets, used and unused, in my suitcase that I shall never throw away. But my most treasured metro ticket is bigger, in an unprepossessing brown color. It was my weekly metro ticket from 1969, dutifully punched twice a day by a long retired, now redundant poinçonneur.

A plastic travel pass will never hold such memories.

Lead photo credit : Paris Metro Ticket, Creative Commons

More in Metro ticket Paris, Navigo Pass, Paris Metro Ticket

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY