A Wildlife Sanctuary in the World’s Most Famous Cemetery

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Père Lachaise is the most visited cemetery in the world, the final resting place of a multitude of world-famous people, and without its graves, the largest park in Paris. And despite its 3 million visitors each year, it is still a working cemetery, burying the remains or scattering the ashes of around 3,000 people each year.

It is also the oldest cemetery in Paris. By the early 19th century Paris’s parish churchyards were filled to bursting – literally. In 1780 one of the mass graves in the churchyard of Holy Innocents, next to Les Halles, collapsed, spewing hundreds of skeletons and decomposing corpses into the cellars of neighboring homes. Pretty traumatic for the inhabitants, you would think.

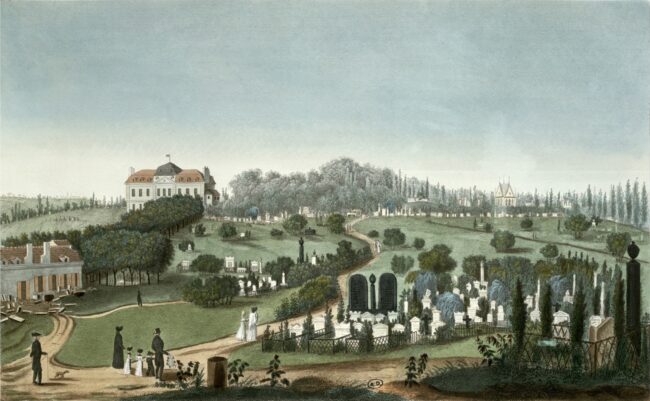

Looking down the hill at Père Lachaise. Photo: Näkymä Père-Lachaiseen/ Public Domain

It took Napoleon to codify rules for burying the dead in secular cemeteries outside towns and cities. In 1804 the City of Paris bought a parcel of land between the villages of Ménilmontant and Charonne, where it laid out the first cemetery in France to conform to the new rules. Its official name, Cimetière de l’Est, was soon supplanted by that of the Jesuit priest who was Louis XIV’s confessor and who regularly retreated to the Jesuits’ country house on the hill known as Mont Louis. He was, of course, le Père Lachaise.

At first, Père Lachaise struggled, partly because it was a long way out of town. Things started to change in 1816 when the remains of two of France’s best-known and beloved writers, Molière and Jean La Fontaine, were moved there. There was a genuine reason but it was also a great PR opportunity to advertise the cemetery. Six months later, the remains of the ill-fated medieval lovers Heloïse and Abelard also arrived. Now Père Lachaise had celebrity tombs and people started to queue up to buy concessions (the system of leasing burial plots or family sepulchres).

View of Pere Lachaise Cemetery from the Entrance, 1815 (colour engraving) by Courvoisier, Pierre (1756-1804) (after); Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs, Paris. Public domain

The cemetery was extended several times during the 19th century, the newer part towards the rear being laid out in a utilitarian grid pattern while the original cemetery climbing the hill from Boulevard de Ménilmontant had been deliberately laid out to resemble a park in the English landscape style with winding, bucolic lanes and paths and lots of trees.

Now, 220 years later, the cemetery has evolved into a thriving wildlife haven. In 2011 the Ville de Paris started phasing out the use of synthetic pesticides until, by 2015, none of its parks and gardens were sprayed. The change everywhere has been striking and nowhere more so than in the city’s cemeteries. For a naturalist Père Lachaise has become quite a nature reserve. Where, before, the graves were separated by arid, graveled paths and the paved avenues were regularly cleared, wildflowers and grasses have returned – some might say “invaded.”

Moss in Père-Lachaise Cemetery. Photo: Guilhem Vellut / Wikimedia commons

Some older residents still complain about the “state” of the cemetery, considering its rewilding to mean neglect, and bewailing the apparently uncontrolled profusion of plants that some might consider weeds. But these wild flowers attract a multitude of insects, including butterflies and hoverflies but also ground insects such as beetles, worms, spiders, and millipedes. In their turn, the insects support dozens of species of birds and small mammals which in turn help distribute seeds across the cemetery.

Not only that, but the wild flowers provide bright splashes of color throughout the growing season, from violets, pink Herb Robert and purple bittersweet nightshade in spring, to the yellow flowers of St John’s Wort, mauve creeping thistle and yellow ox-tongue in summer. This latter is a favorite food supply for the hoverfly, often mistaken for a wasp owing to its yellow-and-black striped body but smaller, without a sting and a true friend of an organic garden. Between 2010-2020 more than 220 species of plant were recorded including ferns, mosses and lichens (which need clean air to thrive) as well as the flowering plants.

In summer, the canopies of mature trees provide welcome shade from the heat. The principal species are horse chestnut, maple, beech, oak, plane and lime. It has been calculated that there is a tree for every 17 tombs. In fall it is a never-ending job to sweep the dead leaves, which can be a safety hazard on wet, paved paths that are already slippery. In several places plane trees have invaded abandoned graves, the roots entwining metal grilles, pushing headstones out of place, even growing inside or on the roofs of sepulchres. The worst problem, though, is storms. With many of the trees nearly 200 years old, a storm-force wind blowing through an old tree next to a tomb is a disaster waiting to happen.

Nine trees are classed as arbres remarquables, a designation bestowed on a tree for its age, interesting history and origin. At Père Lachaise you will find a gum tree, the only species of rubber tree to grow in a temperate climate, as well as a Canadian “bone tree,” so-called because it is denuded of leaves for half the year so it usually looks dead, two gingko trees, and a Montpellier maple planted in 1833 and the oldest specimen of its kind in Paris.

View this post on Instagram

And where you have trees, of course, you have birds. The ubiquitous green parakeets have colonized, of course, but even commonplace species like tits (the blue tit, coal tit and long-tailed tit all call Père Lachaise home) and robins are welcome in a densely-populated urban environment. It’s not uncommon to hear a woodpecker tapping away at a tree trunk but you don’t even have to be in the cemetery to enjoy the birdsong: the beautiful tuneful song of the blackbird can be heard half a kilometer away through open apartment windows during spring and summer. Less beautiful, crows are common neighbors for nearby apartments. Occasionally you can even hear a buzzard, while inside the cemetery the noisy jay, chaffinches, goldcrests and thrushes all thrive. In the autumn starlings take over. Even in the darkness of night a resident tawny owl has been seen and heard.

Two birds on a cross in Père-Lachaise. Photo: jphilipg / Wikimedia commons.

All of this wildlife is meticulously photographed by the cemetery’s live-in keeper, Benoît Gallot. The son of a funerary stonemason, he actually trained to be a lawyer but when the opportunity to work in a cemetery came up it seemed like destiny was calling. His first job was actually at Père Lachaise, working as an assistant in the department of concessions, before moving on as a cemetery keeper at Ivry, in the south of Paris. In 2018 he was promoted to cemetery keeper at Père Lachaise.

Having been a keen photographer in his youth, his camera had lain unused for several years. Then Covid arrived and lockdown: the cemetery was busier than it had ever been, and not in a good way. To help take his mind off work, Gallot dusted off his camera and started to capture the life that was burgeoning all around him. The lack of visitors encouraged previously shy animals to emerge but Gallot’s “lightbulb moment” came on April 23, 2020 when he came across a fox cub on the path ahead of him. After several return visits to the same spot, he saw the vixen, and the fox family became “a bubble of hope” during the darkest months of Covid. Since then the foxes of Père Lachaise have become the stars of Gallot’s social media.

In 2022, Gallot wrote a memoir of Père Lachaise called La Vie Secrète d’un Cimetière (The Secret Life of a Cemetery, Greystone Books, 2025), which has just been published in English. It’s full of Gallot’s own photographs depicting Père Lachaise through the seasons, and closeups of some of its inhabitants including, of course, the foxes. It’s also a fascinating history of the cemetery and some of its most famous human residents, as well as a behind-the-scenes look at its work today and an account of Gallot’s own journey from would-be lawyer to guardian of the most famous cemetery in the world. He lives with his family in an apartment inside the administration building by the main entrance, and often films wildlife he can see from his kitchen window. He is sometimes asked what his children think of living in a cemetery and it doesn’t seem to faze them a bit. To them it is like having a park outside the front door, and certainly during Covid they could safely explore without fear of any visitors. Gallot even set them the task of noting any apparently abandoned plots and sepulchres, which he could then offer to new families.

You may not see a fox during the daytime (although cats are as numerous as any other Parisian cemetery), but Père Lachaise remains a beautiful place to wander, explore, and reflect upon the hopes, ambitions and fears of those thousands of lives whose only memorial to posterity is a gravestone. Possibly a mossy one with a cheeky robin or blue tit perched on top.

The Secret Life of a Cemetery by Benoît Gallot

Lead photo credit : Eurasian jay in Père-Lachaise. Photo: FreCha / Wikimedia commons

More in cemetery, green, nature, Père-Lachaise