Flâneries in Paris: A Riverside Loop from Châtelet

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 22nd in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

Four sphinx statues greeted me at exit 16 of the enormous Châtelet metro station. They gazed wisely down from around the fountain on the little square, referencing both ancient culture in faraway Egypt and the 19th-century emperor who seeps into everything in Paris, Napoleon. For it was he who commissioned the fountain, a gift of eau potable to Parisians, wrapped up in a reminder of the country where he’d recently been on a campaign. I realized later that the mingling of historical eras was to become a major theme of this walk, a circular route starting at Châtelet.

Sphinx at Place du Châtelet. Photo credit: Marian Jones

The Place du Châtelet leads straight to the Pont au Change, one of the city’s lesser-known bridges, but one which affords wonderful views. Just downriver is the Pont Neuf, the city’s oldest bridge, whose stone arches stretch across the Seine, connecting the Île de la Cité to both the right and left banks. And, ahead of me on the opposite bank, the Conciergerie, aesthetically perhaps my favorite building in the whole of Paris, despite its terrifying past. The former royal palace stretches along the riverbank, its cream stone facades interrupted by turreted towers with slate-grey pointy hats, a unified whole of understated Parisian elegance.

Palais de Justice, Conciergerie and Pont au Change around 1900. Public domain

When I turned right at the end of the bridge, I found the Quai de l’Horloge was full of people, seemingly from all corners of the globe and all talking at once. Groups of excited teenagers thronged past parties of elderly tourists, all following various tour guide symbols: flags, a bright orange beret, an Eiffel Tower logo. I went down the steps to the riverside path where it was much quieter. Pleasure boats floated by and so did a barge, piled high with Franprix loading boxes, a reminder that the Seine is a working river. I smiled at the shoe shop on the riverbank, called not Père et Fils (Father and Son), but Paire et Fils. I do love a wordplay, especially in a foreign language!

View of Pont Neuf. Photo credit: Marian Jones

A little further along came the imposing statue of Henri IV, gazing down from the Pont Neuf, the bridge which was completed during his reign. He’s astride his horse, trotting purposefully along, his confident expression giving no clue to the fate which would end his successful reign, namely assassination by a religious fanatic in May 1610. The statue was destroyed during the French Revolution, but rebuilt in 1810, almost exactly 200 years after Henri’s death. Today, he is one of France’s most admired monarchs, although his nickname, le Vert Galant, is a reminder of his lively personality and many mistresses.

View of the Pont-Neuf bridge in Paris. Photo credit: Sumit Surai/ Wikimedia Commons

I always like to pop down the steps behind Henri’s statue to the little park, the Square du Vert Galant, which is in fact triangular in shape. It tapers to a point, the western end of the île de la Cité, and is lined with benches, offering a good spot for Parisian office workers to eat their lunchtime sandwich. Ernest Hemingway loved it here too and in A Moveable Feast he described picnicking here with a bottle of wine, some bread and sausage and a good book. He also liked to watch the fishermen who sometimes offered him some of their catch, “dace-like fish that were called goujon. They were delicious fried whole and I could eat a plateful.”

The square du Vert-Galant, on the île de la Cité. Photo credit: Rafael Garcia-Suarez/Wikimedia Commons

Coming out of the park’s entrance, I turned down the riverside path which led back under the Pont Neuf and past a high wall studded with large iron rings for mooring boats. Down here it was tranquil, just a few other walkers and a few tourist boats, including one called the Jeanne Moreau. When the path sloped up to rejoin the Quai des Orfèvres, the road had a different atmosphere, quieter, with a weighty seriousness. A dozen police vans were lined up in pairs and on the huge stone building to my left was a Latin inscription looping under a clock with roman numerals and carved decorations.

I spotted the wording Tribunal Correctionel and the penny dropped. I was passing the court where criminal cases are tried and the Latin inscription underlined the importance of the law: Hora fugit stat jus, “Time passes, the law remains.” I remembered that number 36, Quai des Orfèvres is the address of the police HQ in Georges Simenon’s novels and that the street name is also the title of a popular post-war film, described at the time by the Washington Post as “a fine, engrossing French crime film.” When I checked, I discovered that this was, until very recently, indeed the site of the main Police Headquarters, but that in 2018 they relocated to the 18th arrondissement.

Tribunal Correctionnel. Photo credit: Marian Jones

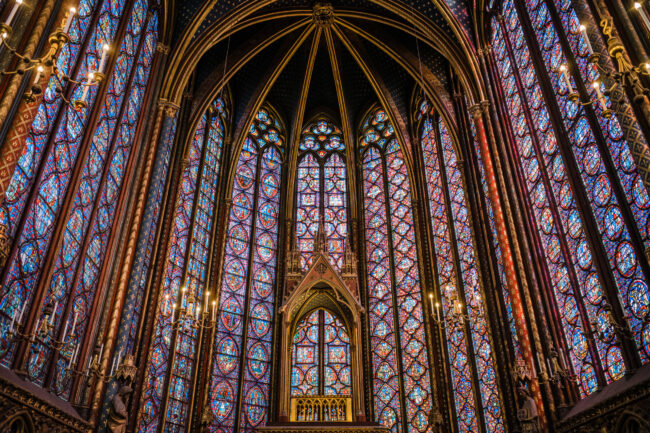

As I rounded the corner into the Boulevard du Palais and saw an overhead sign marking accès public to the Palais de Justice, I mused that justice – or what passed for it – has long been dispensed in this corner of Paris. Medieval kings held court in the Conciergerie, hearing pleas and pardoning or condemning their subjects. During the revolution it became a place of terror where so many prisoners were tried and sentenced. From here they were taken in an open cart, to the square now called Place de la Concorde, where the guillotine awaited. And yet here too was a long queue, snaking its way into one of the most sublime buildings in the whole of the city, the Sainte Chapelle, a royal chapel with soaring windows of stained glass commissioned in the 13th century by Louis IX.

The apse of the upper chapel, Sainte Chapelle. Photo credit: Oldmanisold / Wikimedia commons

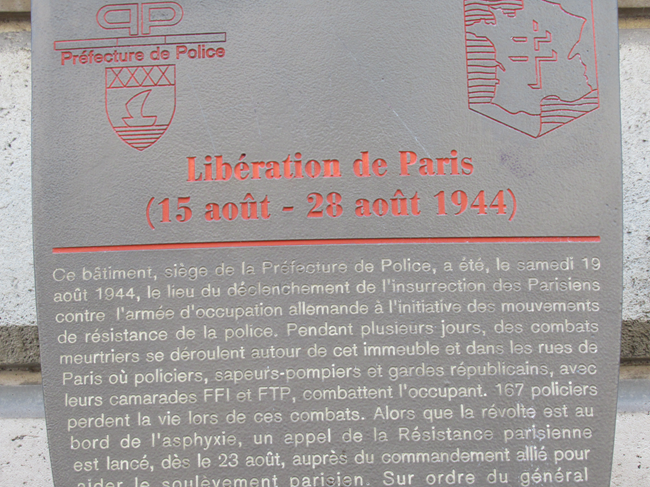

And, just across the road, another of the brown information panels shaped like an oar which relate little snippets of Parisian history at the spots where they happened. For it was here, at the Préfecture de Police in the summer of 1944, that some of the most dramatic incidents of the Liberation of Paris took place. On August 19th, an insurrection against the occupying German troops began and in the street battles which followed over the next few days, 160 policemen lost their lives. Somehow, boosted by Resistance fighters, they held on until Général Leclerc arrived to liberate the city and it was here, on the afternoon of August 25th, that the German General Choltitz was brought to sign the official document of surrender.

Brown oar at Prefecture de Police building. Photo credit: Marian Jones

Just as I arrived back at the Pont au Change I got a close-up view of another Paris landmark. The Tour de l’Horloge stands on the corner where the Boulevard du Palais meets the Quai de l’Horloge and high up on its wall is the first public clock ever installed in Paris. It too represents layers of history. The original clock was installed 1350s and the golden statues flanking it, representing Law and Justice, were added in the 1580s, just a decade after Paris was torn apart by the St Bartholomew Day massacres. It was badly damaged a number of times, but restored, first in the 19th century and again a decade ago.

The clock on the Tour de l’Horloge. Photo credit: Lpele / Wikimedia commons

For me, this stunning clock is a symbol of the care taken to preserve the history of the city of Paris. In 2011, as preparations were made to restore it, medieval documents at the Bibliothèque Nationale were consulted so that, as far as possible, the work of the 14th century’s best artists and craftsmen is still there for us to see today. The gilded carvings and the beautifully proportioned clock face are set against a background of royal blue, dotted with golden fleur-de-lys symbols. I don’t think I could ever pass it without stopping to look up and on this walk it was a fitting last image to take with me across the Pont au Change and back to Châtelet.

The Pont au Change, one of the major bridges connecting the Île de la Cité to the Rive Droite of Paris. Photo credit: Daniel Vorndran / DXR / Wikimedia Commons

Lead photo credit : The Quai de l'Horloge in the 1st Arrondissement of Paris, Photo: DXR/Wikimedia Commons

More in Flâneries in Paris, walking tour