Napoleon’s Elephant

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Victor Hugo once described it as “melancholy, sick, crumbling…unclean, despised, repulsive, and superb, ugly in the eyes of the bourgeois, melancholy in the eyes of the thinker.” It was meant to be a triumphant celebration of Napoleon’s military victories but it ended up as a mouldering, crumbling epitaph to the little general’s overweening egotism. A literal not-so-white elephant.

As any visitor to Paris soon realizes, Napoleon Bonaparte was fond of his grand monuments – the Arc de Triomphe being the grandest of them all. But originally, he envisaged not a triumphal arch but a massive bronze elephant. And not at the top of the Champs Elysées but on the site of the demolished fortress that symbolized the Revolution, the Place de la Bastille. But Napoleon was advised otherwise: eastern Paris was unfashionable and insignificant while the area beyond the Place de la Concorde was ripe for development into a fashionable suburb.

Arc de Triomphe aerial view. Photo credit: Rodrigo Kugnharski / Unsplash

In the first decade of the 19th century, only the lower end of the Champs Elysées had been landscaped by Louis XIV’s garden designer André le Nôtre (up to the Rond Point, the section that is still a park). Further up the hill towards Chaillot was still marshy open ground. However, developers were already eyeing it up and it was suggested to Napoleon that this was a district that could be developed into a smart upper class suburb, attracting the kind of people that he wanted to cultivate and influence.

Always conscious of associating himself with the great rulers of the Roman Empire, Napoleon envisaged a Grand Axe stretching from the Louvre, through the Tuileries Gardens and beyond the Place de la Concorde, equivalent to the great roads leading out of ancient Rome. A ruler-straight road leading to the summit of the Butte de Chaillot, with a monumental bronze elephant on the top, would convey the power and majesty of a modern-day emperor: Napoleon.

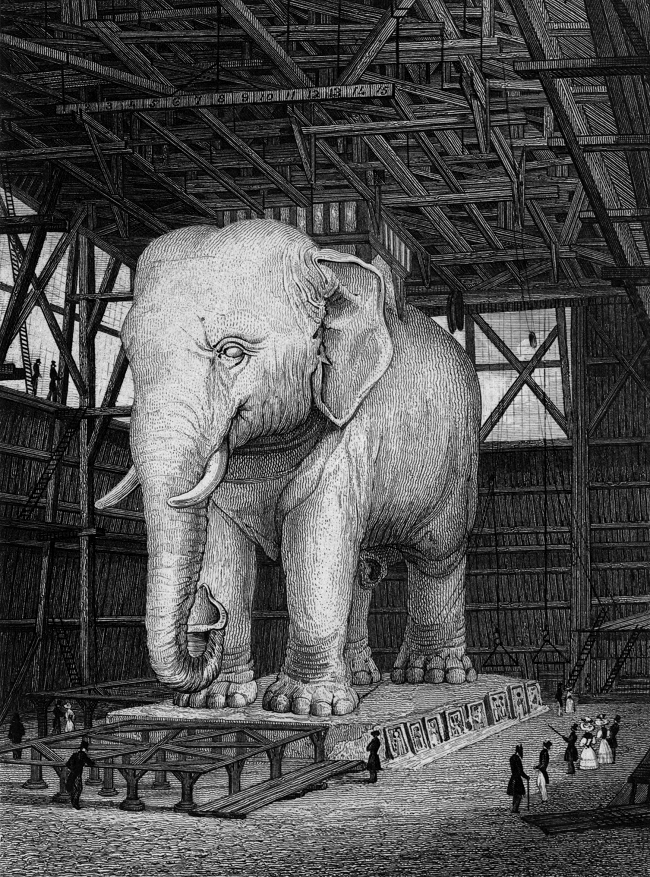

Not only that, but the interior of the animal would be a museum glorifying the achievements of the little ex-corporal. Napoleon could well have been inspired by an earlier plan for a colossal elephant: in the middle of the 18th century the architect Charles Ribart had submitted plans for a three-storey statue with an internal spiral staircase, a ventilation system and a ballroom. Water would flow from the trunk which also incorporated a sewage system (!).

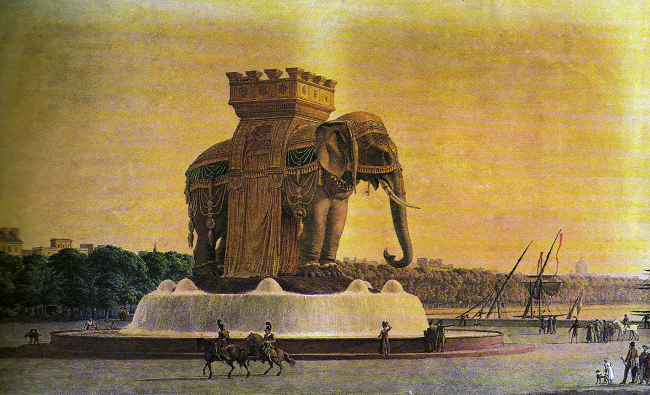

Model of the Elephant for the Place de la Bastille. Artists: Augustus Charles Pugin, Fenner Sears, J. Nash, 1831. Image credit: Brown University Library, public domain.

Except that it didn’t work out that way. The emperor’s advisors thought that an elephant was too original an idea and also -well- a bit low-rent, not conveying the intended grandeur. They persuaded Napoleon that a triumphal arch would be a much more fitting celebration of the general’s military successes. They were right, of course. Even though today’s Champs-Elysées and Étoile are pounded constantly with traffic, there is a monumentalism to the Arc de Triomphe that an elephant, however large, just wouldn’t match.

But Napoleon couldn’t give up the idea of having an elephant monument. In February 1810 he announced the construction of the bronze elephant in the Place de la Bastille. It would have a viewing tower on its back, in the style of an Indian howdah, a staircase built inside one of the legs, and it would be the centerpiece of a fountain, with water spurting from the trunk. The bronze would be made from melted-down cannons seized during Napoleon’s Spanish campaign. It would bury memories of the Revolution by commemorating Napoleon forever.

The architect Pierre-Charles Bridan made a lifesize plaster model to give an impression of what the finished monument would look like, and even mounted it on its plinth in the Place de la Bastille, but sadly, progress got no further than that. Although Napoleon didn’t know it, 1810-11 marked the high point of his military victories. 1812 saw the humiliating retreat from Russia and further slaughters came in 1813. Then, of course, came his exile to Elba in 1814. Neither the desire for grandiose monuments to his exploits nor the money to build them were around any longer and the elephant was never cast in bronze. Instead, its plaster facsimile just stood there on its plinth, overlooking the hustle and bustle of eastern Paris, its regular demonstrations and riots (not much different from today, in fact!).

When the monarchy was restored in 1815, after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo and permanent exile, King Louis XVIII ordered the elephant’s construction in marble. Instead of a monument to military victories, it would be surrounded by sculptures representing more peaceful pursuits: the arts, science and medicine.

Unfortunately, the government was even more hard-up than the latter days of Napoleon so Louis’s plans stayed on the drawing board. The government was able to pay a concierge to supposedly look after the elephant; he lived in one of the legs but did little to repel the ravages of the passing years. Weeds grew up between the animal’s legs and over the plinth. In summer the square was incredibly dusty, which also meant that in winter it was a mudbath so the once-white plaster quickly turned a grubby grey and then black. Efforts were made to level the site but then it was excavated for the Canal Saint Martin and slowly the elephant sank into its own boggy morass. Rain dissolved the plaster and gaping holes opened up which were quickly colonized by rats. The rat problem became so acute that neighboring residents petitioned the city council for the elephant’s demolition because their homes were overrun by the rodents. Not just rats: local homeless people could find rudimentary shelter inside as well.

The underground Canal Saint-Martin in 1862. L. Dumont. Brown University Library, public domain

Neither the city council nor the government seemed to know what to do with it. Tentative plans were put forward to repair and repaint it and put it somewhere less associated with revolutionary fervor – maybe the Tuileries? Or the Invalides? But in the end the crumbling plaster cast stayed where it was. In 1832 it was joined by the tall column celebrating the July Revolution of 1830. It was 1846 before the elephant was finally put out of its misery and demolished.

Gone, but not entirely forgotten: Victor Hugo memorialized it in Les Miserables where the urchin Gavroche lives inside one of the legs. And the elephant makes an appearance in the film adaptation of the musical, where a scene during the 1830 revolution shows Gavroche climbing to the top of it while soldiers and revolutionaries battle in the Place de la Bastille.

Apart from that, very little remains to prove the elephant’s existence. From starting out as a monument to a dictator’s ego, it finally slid into insignificance, a rotting reminder that even the most powerful regimes do not last forever.

Place de la Bastille. Photo credit: ERIC SALARD/Flickr

Lead photo credit : Elephant of the Bastille, around 1810. Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons

More in history, Napoleon, victor hugo

REPLY

REPLY