The Seine Flood of 1910 in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Fluctuat nec mergitur is a Latin mouthful which translates into “she is tossed by the waves but she does not sink.” It’s the motto for the city of Paris. An obvious analogy for resilience and strength, it’s an odd saying for a city on a river, not the sea. Nevertheless, the residents of Paris, as far back as the Roman city of Lutetia, have needed the resilience and strength to deal with the flooding of the Seine.

Today no one is around to recall the flood of 1910, but it remains in the city’s consciousness. Not only was the height of the Seine memorable, but also for the first time, images of its high waters were recorded in news of the day. The bricks and mortar of Paris remember too.

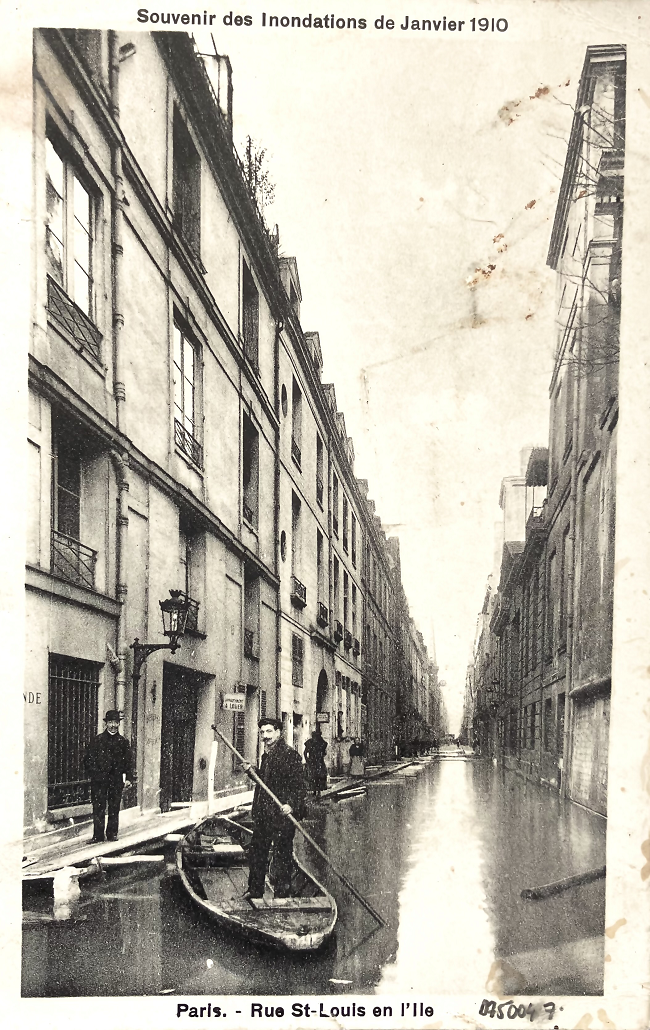

Sepia photographs and postcards (some still for sale at the bouquinistes) showed bowler-hatted men traveling piggyback, their trousers rolled up to their knees. These vintage photos show how the murky, debris-strewn water erased the banks of the Seine and turned streets into canals and public squares in lagoons. Almost overnight, the Seine had turned Paris into the Venice of France, with Parisian gondoliers offering rescue and food to those residents stranded in their homes.

The flood on avenue Montaigne. Photo Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain.

In late January 1910, the Seine had peaked to 20 feet (6m) above its usual height – the highest level the river had measured in 250 years. Northern France had experienced a perfect storm of events that led to the drowning not just of Paris but the entire region. Temperatures were unusually warm and weeks of winter rain and snow left the soil saturated; the tributaries of the Seine began to overflow. At Monet’s garden at Giverny, 50 miles (80km) northwest of Paris, the Seine flood covered the artist’s Japanese bridge, causing him great distress.

However, Parisians were unalarmed. They’d become accustomed to the Seine rising in January. Ironically, it was believed that Baron Haussmann’s modernization of the city’s water and sewage system assured further protection. The sewers were supposed to drain the excess water away. It wasn’t possible, they thought, for flooding to occur at catastrophic levels any longer.

The Seine usually sets its own level at more than 30 feet (9.1m) below the street-level quays. Parisians to this day commonly measure the height of the floods on the statues ornamenting the span of the Pont d’Alma, especially that of the Zouave. This colonial solider stares down the length of the Seine with one foot in front of the other. Parisians of 1910 paid little attention when the Seine was lapping at his boots.

Quai des Grands-Augustins, Rue Gît-le-Cœur during the flood of 1910 in Paris. Photo credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France/ Public domain

However, by Friday the 28th of January, in the space of a week, the Seine climbed higher than any living soul had seen. The river turned a preternatural shade of yellow and picked up in speed. Soon the Zouave was up to his neck. The water was 20 feet (6m) above normal.

City engineers sandbagged the most vulnerable neighborhoods. Twelve of Paris’s arrondissements flooded, hundreds of streets were impassable and thousands of citizens had to leave their homes. Public transport suffered major disruption. Water flooded into the metro lines. Old photos show men punting in the Odeon Metro Station.

Most of the city was without electricity and the waterlogged streets became even more sinister when the gas lamps finally gave out. Public clocks, elevators, and factories ground to a halt. Telegraph and telephone service went out. The flooded basements caused roads and sidewalks to collapse. The Champ de Mars beneath the feet of the Eiffel Tower was submerged. The faithful pulled up to Notre Dame in rowboats as cargo, furniture and stocks of every description floated down the river.

Albert Pierson. “Notre-Dame vue du quai de la Tournelle pendant les inondations de 1910”, 30 janvier 1910. Huile sur toile. Paris, musée Carnavalet.

Citizens moved around the city via wooden walkways called passerelles which crossed the icy January waters. The sewer system suffered major disruptions. Garbage was dumped directly into the pestilent water which became even more undrinkable.

The spectre of typhoid haunted the city. Paris’s Prefect of Police, Louis Lépine was an exceptionally capable problem-solver and soon eased the public’s health concerns. Lépine, endowed with a military sense of discipline, stoicism and courage, also had with an earnest desire to keep Parisians safe. His responsibilities extended to both street and river traffic, train schedules, fire-management, communications, and the supply of food. Train stations became emergency shelters. La Croix-Rouge handed out a hundred thousand loaves of bread every day. Lépine issued detailed cleaning instructions to the entire population, and posters explaining the procedure quickly went up through the city. All infected buildings would remain empty until decontaminated.

The Fontaine de Mars during the flood of 1910 in Paris. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Nine out of 10 Parisians thought the flood would never stop; it was surely the end of the world. At its peak on January 28, the Seine reach a height of 28 feet (8.62m) and flowed at ten times its normal volume. The inundation lasted for 45 days with water receding and rising several times before its mid-March departure. It is said that reparations cost the modern equivalent of 1.5 billion euros. England, Turkey and Australia and the cities of Vienna and Prague, even stepped up to lend financial assistance.

Markers that record the Seine’s high waters are located in many spots throughout the city. Look for the words Crue, Janvier 1910, or just an underlined 1910 on Paris’s bricks. An arch at the Bassin de l’Arsenal shows the heights of Paris’s famous floods. Roman numerals indicate the height of the Seine near the Tour de l’Horloge at the Pont au Change where one can be relieved that the waters of the floods of 1740 were much, much higher.

To name a few, markers are found at: 1 Rue des Ursins in the 4th arrondissment; in the main hall of the Conciergerie; at 18 rue de Bellechasse on the door of the Academie of Agriculture; on the Fontaine de Mars on Rue Saint-Dominique in the 7th; and the parish church of Saint-Antoine des Quinze-Vingts at 57 Rue Traversière. There are many reminders of the quais and bridges of Paris too.

Académie d’agriculture, rue de Bellechasse, Paris 7th arrondissement. Door is inscribed with a level sign from the 1910 flood. Photo credit: Poulpy / Wikimedia Commons

The worst recorded flood happened in 1658 when the Seine swelled to 29 feet (8.8m) above normal. 1924 and 1955 also saw flooding in Paris and the entire Seine basin. The Seine has risen almost as high in recent years. In January of 2018 the Seine rose to 19.2 feet (5.85m) above normal levels, and in 2016, 20 feet or (6.1m)

Today the level and flow rates of the Seine are constantly monitored by a company called Ultraflux, which reports to the flood-warning department for the territory of the Seine Basin. There are a dozen points of measurement situated in Paris and upstream of the capital. This data makes it possible to manage road closures along riverbanks and other measures to protect public roads and sanitation networks in case of flooding. One of the points for measuring the level of the Seine is situated under the Pont d’Austerlitz in the heart of Paris. While nature is unpredictable and the effects of global warming largely unknown, perhaps these steps can ameliorate the next rise in the Seine.

Rue Saint Louis en l’ile, vintage postcard. Collection of Hazel Smith

Lead photo credit : Zouave statue during the flood of the Seine in Paris, January 26, 2018. Photo credit: Ibex73/ Wikimedia Commons