Flâneries in Paris: Explore a Corner of Montparnasse

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 29th in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

Simone de Beauvoir liked the crossroads where I began this month’s walk. “I have a strange attachment to the carrefour Montparnasse,” she wrote, referring to the spot where the Boulevard Montparnasse meets the Boulevard Raspail. And so do I. It’s a place to get lost in reveries.

An old photo on La Rotonde’s website shows a scene from soon after the restaurant’s opening in 1911. Tables are jammed in all over the pavement, dominating the intersection of the two boulevards and spilling over with chattering customers. Ties and bowler hats for the men, the tight-bodiced gowns and feathered hats of the ladies just beginning to give way to looser dresses, straw boaters and the cloche hats which would take over in the 20s. It’s a gathering of the leisured classes, some perhaps planning a day at the races, others maybe swapping notes on the previous evening at the opera.

But impoverished writers and artists clustered here too, especially during the 1920s. Rents were cheap, the café-owners allowed them to linger long over one drink, perhaps to pay a bill in kind, with a drawing or a wall painting. I pictured Hemingway in a café corner, sharpening the two pencils he kept in his pocket before tuning out from the hubbub around him and getting lost in a story. I imagined him drinking on a terrace with F Scott Fitzgerald, I pictured Modigliani and Picasso analyzing each other’s work, I wondered if Gershwin ever chatted with Josephine Baker. For they were all “Montparnos.”

La Rotonde. Photo: Marian Jones

I admired the red cane chairs with gold trim which adorn the terrace of La Rotonde today and paused to take a photo of its distinctive red canopy with golden lettering. It formed a backdrop to signs pointing to two of the most iconic locations in Paris: right for Saint-Germain-des-Près, left for Montparnasse. Carried away by these romantic names, I decided to become a cliché. Fifteen euros would buy me breakfast at one of Montparnasse’s best-known cafes, notebook ostentatiously open before me. A waitress might cast me a knowing “ah, another wannabe writer” glance, but that would not diminish my excitement one jot!

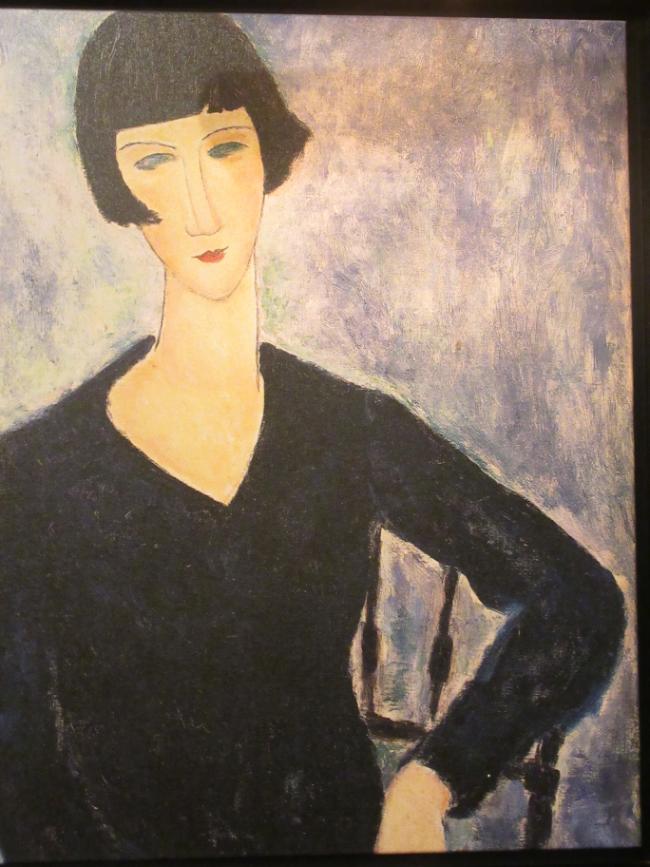

Inside, the early 20th-century elegance was immediately visible. The dark polished wood, plush red velvet seating and golden lamps showed that the restaurant, said to be a favorite with President Macron, has gone upmarket. Yet the Modigliani prints on the walls recalled the days when impoverished artists gathered there and the waiters turned a blind eye if they pinched the end of a baguette from someone else’s table. On this particular weekday morning, La Rotonde was curiously empty. The only customers I saw as I entered were two or three lone businessmen despatching their breakfasts without looking up from their phones.

Modigliani print on the wall at La Rotonde. Photo: Marian Jones

The breakfast formule – orange juice, coffee, a ficelle, a croissant, butter and jam – arrived on an elegant white oblong plate Juste comme il faut, I thought, the perfect petit déjeuner. It seemed a pity to disrupt the design by creating a pile of flakes and crumbs, so first I took a photograph for posterity. The waitress affected not to notice, but I just know I had “tourist” stamped large on my forehead. No matter. It was worth it. On leaving, I noticed a backpacker lingering over a coffee in one of the window seats. A kindred spirit?

My plan was to stroll around the other cafes which make this corner legendary, then wander through nearby Montparnasse cemetery where so many of the area’s famous past residents are buried. Just opposite La Rotonde is Le Dôme, where the beautiful Art Déco windows along its Rue Delambre side and the Menu Ernest Hemingway displayed prominently at the main entrance both spoke of its illustrious past. I remembered Simone de Beauvoir’s description of it during the Occupation, when she saw the occupying German troops bringing their own coffee for the staff to prepare, while French customers were reduced to drinking what she called “some anonymous and ghastly substitute.”

A little further up the Boulevard Montparnasse, La Coupole and Le Select sit opposite each other. I passed by La Coupole this time, remembering a previous visit when I’d eaten on the terrace and managed to sneak a peek into the downstairs dance hall, a low-ceilinged room with a bar at one end. There, jostling crowds gathered in the 1920s to hear the jazz music which had taken over Paris and danced in the space made by pushing all the tables aside.

Le Select was the first of the popular Montparnasse cafés to stay open 24 hours a day, making it an early favorite of the Montparnasse crowd. The understated cream and gold décor of today masks its riotous past – Isadora Duncan once flung a saucer across the room – and also hides its history as a safe haven for society’s outcasts. For here, gays were welcome during the Nazi occupation of the city and after World War II, customers included Jewish artists such as Isaac Frenkel and Emmanuel Mané-Katz. One café stop per flânerie is enough, but I resolved to return one day and try the great value menu: 25 euros for two courses, wine and coffee.

Le Select, 99 boulevard du Montparnasse. Credit: Celette/ Wikimedia Commons

My route to Montparnasse cemetery took me a little way up the Boulevard Raspail, then right into Rue Huyghens, where a black marble plaque on the wall of a school was a memorial to the “more than 120 children” from the 14th arrondissement who died in the death camps during World War II because, to translate the stark wording, ‘”they were born Jewish.” This reminder of past horrors jolted me out of my romantic musings about cafés and artists, putting the complaints about tasteless ersatz coffee into perspective. I appreciated the honesty of the wording which attributed the atrocities of the 1940s not just to la barbarie nazi, but also to la complicité of the Vichy government.

The information board at the entrance to the cemetery promised a green space, planted with over 1200 trees and 38,000 tombs, including those of “well-known figures from the world of art and literature.” There’s an urban feel round the cemetery’s edges. The backdrop to the jumble of graves and sepulchres is often an unexpected tower, or a block of flats whose balconies overlook the grounds. The graves of the writers, artists and musicians who chose to be buried here – you can download a map listing over 100 – are dotted among all the others. Just to the right of the entrance, is one of the best-known graves of all, where Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir are buried together.

Beauvoir’s and Sartre’s grave at the Cimetière du Montparnasse. Photo: Aerin/ Wikimedia commons

The two writers are remembered in the very simplest of words, just a name and dates of birth and death for each. But the grave’s many visitors have not been content to leave it like that. They have scrawled hearts all over it in pink lipstick, some obviously recent and others fading to a mournful brown. Would the two authors have found it tawdry? Or, having broken so many conventions themselves, would they have seen it as recognition? Personally, I found it disrespectful and I wondered how many of these “artists” had actually read Les Mains Sales or Le Deuxième Sexe. Even if they admire these works, how does defacing their authors’ graves pay any kind of tribute?

From there, I went a-wandering. One grave which stood out was that of Henri Laurens, because sitting on top was a large, modernistic statue of a hunched figure. Research revealed that it was by Laurens himself and that he was a stonemason-turned sculptor, influenced first by Rodin and later by Picasso, whom he met here in Montparnasse in about 1915. Later I came across the grave of Alex Berdal, one-time winner, said the inscription, of the Prix de Rome. Here too was a piece of the artist’s work, a large sculpture in the shape of a fish, but whose side was carved into the shape of female breasts. It seemed very Montparnasse, somehow.

Hidden among the inscriptions were so many poignant stories; an elderly couple, Ernest and Claire Heilbronn, who were both nearly 80 when they died together at Auschwitz; a Lithuanian noble, Joseph Straszewicz, who died in exile in Paris after a failed insurrection against the Russian empire; an apple with Merci Monsieur Chirac penned onto it, resting in a plant pot on the former president’s grave; a plot where children have left a tiny wooden rocking horse and a heart inscribed Papa, mon héros; a color photograph of a smiling teenager on a beach, the dates showing that she was only 13 when she died. Alongside it was the full text of Victor Hugo’s poem, Demain, dès l’aube (Tomorrow, at Dawn) where the author writes of rising early to cross forests and mountains before placing flowering heather on a grave. He wrote it four years after the death of his 19-year-old daughter Léopoldine.

Montparnasse cemetery sits well in this little corner of Paris. Among the names of local residents are sprinkled others which recall its special role in artistic circles. For here are authors – Maupassant, Becket, Susan Sontag – alongside sculptors – Bartholdi, Zadkine – and stars from the world of film – Eric Rohmer, Jean Seberg. My walk had taken me through the café culture and the artistic heritage of Montparnasse, the two aspects for which it will always be so fondly remembered.

Montparnasse Cemetery. Photo: Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Boulevard Montparnasse street sign. Photo: Marian Jones

More in Cafes, Flâneries in Paris, Montparnasse, Montparnasse Cemetery, walking tour

REPLY