C’est Pas Moi: Léos Carax’s Anti-Auto-Biopic

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

For years now Léos Carax has been the visionary mystery man of French cinema. Even his name is an anagram derived from his real name, Alexandre (DuPont) and Oscar (why Oscar? another mystery, though it’s the name of at least one alter ego). His reputation looms large but he’s only made a handful of strange and evocative films. I thought his last, Annette (with Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard) was brilliant but audience-punishing. Now C’est Pas Moi (literally It’s Not Me), is both his most personal film, a meditative “auto-biopic”, and his most confounding.

Before becoming a mystery man Carax was a wunderkind. In the 1980s several young French filmmakers came to the fore to shake up the post-New Wave scene: Jean-Jacques Beneix with Diva, Luc Besson with Subway, Jean-Jacques Annaud with Quest for Fire. With Léos Carax we got moody takes on the love story (Boy Meets Girl) and romantic noir (Mauvais Sang). He was the most intriguing of these new directors, a filmic Rimbaud. He crowned his early body of work with Les Amants du Pont Neuf (1991), a love story that was harshly realistic and deliriously romantic, another step forward for his alter-ego Denis Lavant as well as a brilliant role for Juliette Binoche. But his later films came at wider intervals and seemed willfully obscure: Pola X (1999), Holy Motors (2012), Annette (2022).

Leos Carax at the Festival de Cannes, in July 2021. Photo: Canal22/ Wikimedia commons

In C’est Pas Moi, Carax abandons narrative altogether in favor of a collection of images, many of them archival, some extracts from films, and some which are dramatized vignettes he shot himself. There are snatches of dialogue but also music and voice-over, as well as superimposed text. The sheer number of image-shards, the way certain images have been manipulated, and the film’s rhythms are reminiscent of experimental director Stan Brakhage.

Brakhage was much more radical, a movie equivalent of Jackson Pollock. The better

reference here is Jean-Luc Godard, who’s always been an influence and idol of Carax.

Godard made late-phase films with only a rudimentary story, impressive collages featuring beautiful images, and also experimented with video and 3D. But he always had a definite theme: Cinema, History, Europe. His voice-overs and texts were quintessential Godard, idiosyncratic and pedagogical. My problem with these films was their impersonality: they came from the Olympian heights. Carax is more personal: he speaks (albeit obliquely) about his family heritage, the passage of time in his life, his tortured relationships.

Film poster for “Annette”

One Carax fun fact is that his mother is American movie critic Joan DuPont. Just as the young Carax conjures a magic moment in the ‘80s, when French cinema was re-inventing itself (as was French society after the election of François Mitterrand), Ms. DuPont brings back the pre-millennial era from a different perspective: the American diaspora and its cultural infrastructure (in her case the International Herald Tribune, a later incarnation of the paper Jean Seburg hawks in Godard’s Breathless). Carax’s mother is of Russian-Jewish origin, which also gives Carax a special feeling for the Holocaust, WWII, and the Cold War.

And so we get bits of home movies and photographs of little Leo (or rather Alex) with his family, archival images of the war, cryptic text messages. Would we appreciate these associations and allusions if we didn’t know about Carax’s bio beforehand? Not really. I felt there was much that I was missing that I wouldn’t have if I’d been following stories about his life over the years.

Leos Carax during his masterclass at la Cinémathèque française in March 2023. Photo: ManoSolo13241324 / Wikimedia commons

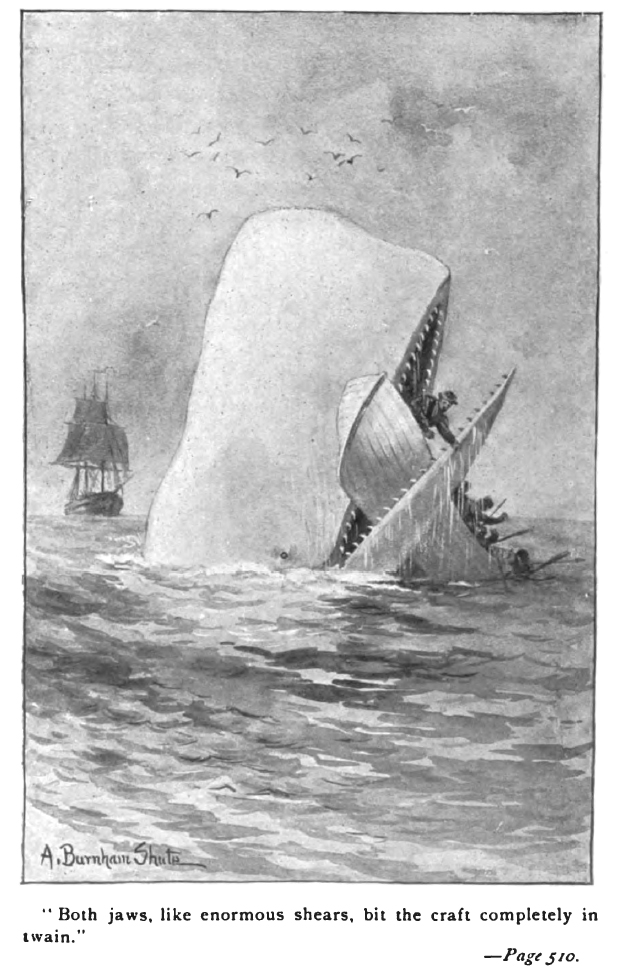

One of the stars of Pola X was the Russian actress, Yekaterina Golubeva. After making the film, Carax and Ms. Golubeva subsequently married and had a daughter, Nastya. Tragically, Ms. Golubeva later committed suicide. A tragic irony is that Pola X is based on Herman Melville’s Pierre, or the Ambiguities, and the character she was playing also commits suicide.

The images relating to the film, to Ms. Golubeva, to the situation in Russia (images of Putin and Pussy Riot) are terribly poignant. There are also images of their grown daughter playing piano and home-movie images of Carax and Nastya as a child walking on a boardwalk (perhaps filmed by the mother).

Moby Dick attacking a whaling boat. Image: Augustus Burnham Shute – Moby-Dick edition – C. H. Simonds Co. Public domain

The images’ meanings aren’t spelled out in the film, so it’s up to the viewer to get the back story — or else let the images speak for themselves. (What if we didn’t know that the white whale in Moby Dick had bitten off one of Captain Ahab’s limbs?) Yes, we can enjoy the tumble of images, the word-play of the texts. Carax is never un-interesting. But a little research can go a long way, and turn what was mystifying into something more profound and haunting. One might also see the film a second time: C’est Pas Moi is only 45 minutes long (it never drags, but as they say, no one would wish it were longer). Better yet, or in addition: Check out a selection of Carax’s earlier movies.

Lead photo credit : Photo: C'est pas moi 2024 film poster, Wikimedia Commons

More in cinema, Léos Carax, movies, Paris films