From Sainte Chapelle to the Bibliothèque nationale de France

Philosophy professor John Eigenauer shares fascinating and unknown histories of Paris in “The Smart Side of Paris” series

By all accounts, Baldwin of Courtenay was a less than effective ruler, his incompetence reflected by the handful of living people who have heard his name. How many kings have Wikipedia entries shorter than this article? In his defense, he governed a once proud but dying city, living in isolation in Constantinople. There, poverty was inevitable, as was losing his precious lands without the money to pay his armies.

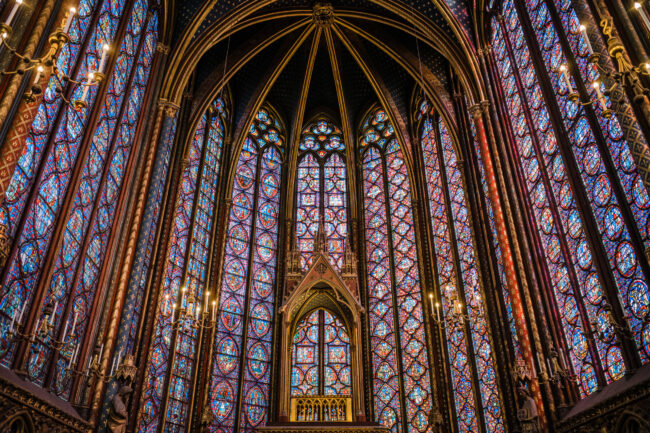

Being a long way from Western Europe, he had few ways to raise the funds he needed to sustain his image so, he begged. He made several trips to wealthy royal courts to raise cash, with little success. He was so desperate for money that he pawned the Crown of Thorns — or what people believed was the Crown of Thorns — in 1238 to a representative of the wealthy and powerful Doge of Venice. Later, the inordinately pious Louis IX just had to have it; he purchased it for 10,000 livres (despite claims that the price was 135,000 livres) and had it transported to Paris where he had Sainte-Chapelle built to house it. Nobody would blame you if you read that last sentence again.

The apse of the upper chapel, Sainte Chapelle. Photo credit: Oldmanisold / Wikimedia commons

Baldwin’s luck never changed much, nor did his fundraising strategy. Having pawned the crown of the Son of God, he next used his own son as collateral to obtain loans from Venetian merchants. (The Castilian king, Alfonso X, eventually posted bail, at the behest of his mother, who was Baldwin’s wife and Alfonso’s cousin —thank goodness for nepotism.) In 1245 or 1246, Baldwin traveled to France and sold more “relics” to king Louis IX.

Some 30 years later, in 1279, one of those “relics” appears in an inventory of Sainte Chapelle’s treasury. It was a large piece — a cameo to be exact — that, seen through the biblical myopia of the day, was called the “Triumph of Joseph at the Court of the Pharaoh.” There it languished for more than 60 years until Philip VI, who was also in financial trouble, hocked it to Pope Clement VI, the Avignon Pope, back when the Holy See was in France.

Thirty years later, another Avignon pope, Clement VII, returned this cameo to the Crown of France and it was shuttled back to Sainte Chapelle. And there it would have sat — misidentified — were it not for one of the most remarkable minds of the early 17th century, the now nearly forgotten Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc.

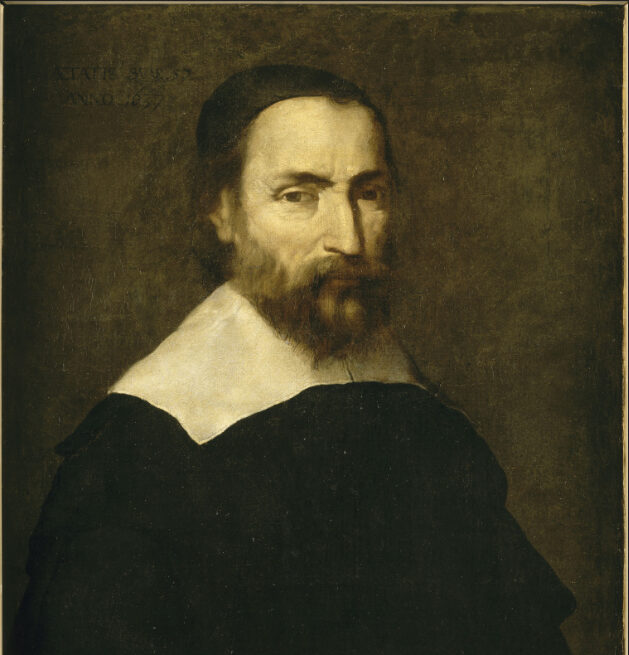

Portrait of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, attributed to Finson Ludovicus (vers 1580-1617). Public domain

In his lifetime Peiresc was called “The Prince of the Republic of Letters.” Those who knew him “thought him to be among the most virtuous and benevolent men who had ever lived,” as I stated in the book Paris and the Birth of Public Knowledge. “His reputation for honesty and generosity were such that books were written holding him up as the model of a good life.” When Galileo ran afoul of the Church in 1633 and was tried by the Inquisition, European scholars called on Peiresc to intervene on his behalf with the Pope. Galileo was condemned to house arrest, but we do not know if Peiresc helped lighten the sentence. (A beautiful example of a letter from Galileo to Peiresc can be found online at the Morgan Library and Museum.)

Reliure en maroquin rouge au Chiffre de Peiresc. Bibliothèque du Patrimoine de Clermont Auvergne Métropole

Despite never having published anything notable, Peiresc was a scholar of phenomenal importance. Over 10,000 of his letters survive today as he communicated with scholars everywhere about everything. He studied astronomy (he was the first to document the Orion Nebula), collected over 18,000 ancient coins and medals (which he studied assiduously), was fascinated by art (he recorded every painting he saw at Fontainebleau), built a library of over 6,000 volumes, learned ancient languages, devoured Greek, Roman, and Egyptian history, sent books to needy scholars, and taught the 17th century’s greatest networker, Marin Mersenne, how to network.

Indeed, his “vast erudition and insatiable curiosity” was so profound that it moved the great artist Peter-Paul Rubens to wonder how “any one person can be so knowledgable about so many things.” When Peiresc died, his friends published a book of poetry honoring him with verses written in “all the world’s known languages” — right down to Quechua (Peter Miller, Peiresc’s Mediterranean World).

Bust of Peiresc by Caffieri (1787) (Bibliothèque Mazarine).

Peiresc was fascinated by the mystery of history. He was the embodiment of a true “antiquarian.” He taught his contemporaries to view ancient history as a puzzle — a giant, beautiful, challenging jigsaw — with pieces of evidence scattered everywhere: in coins and correspondence, in history and heresy, in ruins and in rhetoric. He was something of a stationary Humboldt, exploring the world through books and correspondence rather than by navigating unknown rivers and climbing volcanoes; something of a less skeptical Gibbon, a historian of the ancient world without the subversively ironic Enlightenment flair.

Somehow — I have no idea how — Peiresc came upon the cameo in Sainte Chapelle, now called The Great Cameo of France, and, summoning his vast storehouse of knowledge about the ancient world, declared that the scene depicted was not a biblical story at all, but in fact a work from the first century Roman world created to portray the divine foundation of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. With this, the much-cherished notion that everything old and beautiful must in some way be biblical suffered considerably.

The Great Cameo of France. Photo: John Eigenauer

Much has been written about the Great Cameo of France, and today you can still see it in Paris. By some enormous stroke of luck or genius, Louis XVI saved it by placing it in the Cabinet des médailles during the French Revolution. And from there, it has found its way to the Richelieu branch of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, in the Mazarin room.

Today, you can enjoy the new gardens outside, step inside the new café for tea, visit the magnificent Oval Room (long off limits to visitors), and finally visit the Mazarin Gallery, where you will be greeted by one of the most beautiful pieces of the ancient world. It is easy to walk past the magnificent cameo — which is the first item on display—because the Gallery itself is breathtaking. But if you go, please pause to reflect on the remarkable history of this remarkable object, which we have the good fortune to see because of the poverty of an incompetent king, the ostentatious holiness of a devout king, the secret cabinet of a quick-thinking king—and above all to the curiosity of an antiquarian gentleman who was known as the most honorable person of his age.

DETAILS

Bibliothèque nationale de France (Richelieu site)

The museum is open every day except for Monday.

Ticket price is 10 €

5, rue Vivienne, 2nd arrondissement

The Mazarin Room, Bibliothèque nationale de France (Richelieu). Photo: John Eigenauer

Lead photo credit : The Great Cameo of France, Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Wikimedia Commons

More in The Great Cameo of France, The smart side of Paris

REPLY