The Smart Side of Paris: The Man Who Outshined Napoleon

On September 14, 1869, across America from New York and Boston to small towns in Ohio and Kansas, hundreds of thousands of people celebrated the 100th anniversary of the birth of the most famous person who had ever lived, except perhaps Napoleon. Fifteen thousand people turned out in Syracuse, New York alone. They celebrated in Mexico and Moscow, Adelaide and Amsterdam, Paris and Prague.

Why such a fantastic fête for someone who had died 10 years before? Perhaps because his ideas influenced so many great thinkers. He shaped the way that Thoreau wrote Walden; he counseled Thomas Jefferson on foreign policy; he inspired Simón Bolívar to start a revolution against Spanish imperialism in South America; the great Goëthe found his knowledge to be inexhaustible; he inspired Darwin to take his famous voyage on the Beagle; Jules Verne modeled characters after him; Napoleon hated him for doing more alone than he had done with an army of scientists. Despite his incredible fame, unfathomable accomplishments, and the fact that more places on earth are named after him than any other person, very few people today recognize his name: Alexander von Humboldt.

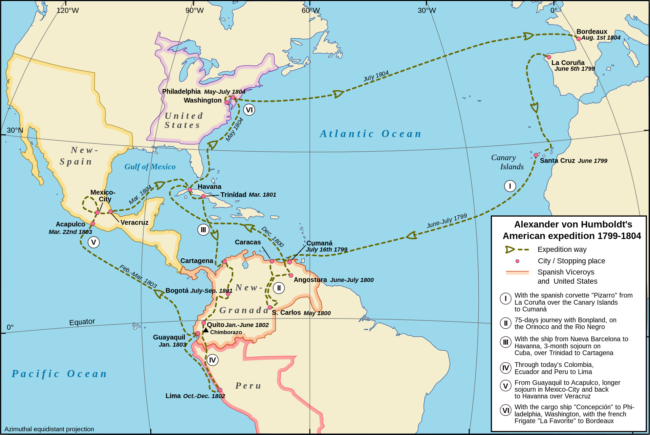

Alexander von Humboldt’s Latin American expedition 1799-1804. Wikimedia commons

In June of 1799, Humboldt left La Coruña, Spain and sailed for South America with the goal of discovering how “all [the] forces of nature are interlaced and interwoven.” He climbed the 12,000 foot volcano in Tenerife without equipment as a warm-up for his South American ventures. He landed in Venezuela and began collecting everything in sight. He ventured into the deepest jungles, handled electric eels, trapped birds, collected plants, and found the mythical Casiquiare River, which connected the Amazon and the Orinoco rivers, and which no European had ever recorded. He climbed the 21,000-foot-high Chimborazo volcano in Ecuador without hiking equipment while his feet were bleeding, bought Aztec manuscripts in Mexico, lived with indigenous tribes in the Amazon, and trekked the 2,500 miles of harsh terrain between Cartagena, Colombia and Lima, Peru. He walked hundreds of miles of muddy paths less than a foot wide, paddled upstream against strong river currents for weeks on end, fought clouds of mosquitos so thick that he inhaled them while breathing, and stopped on his way home to visit with Thomas Jefferson.

Orinoco River, in Amazonas State, Venezuela. Photo credit: Pedro Gutiérrez/ Wikimedia Commons

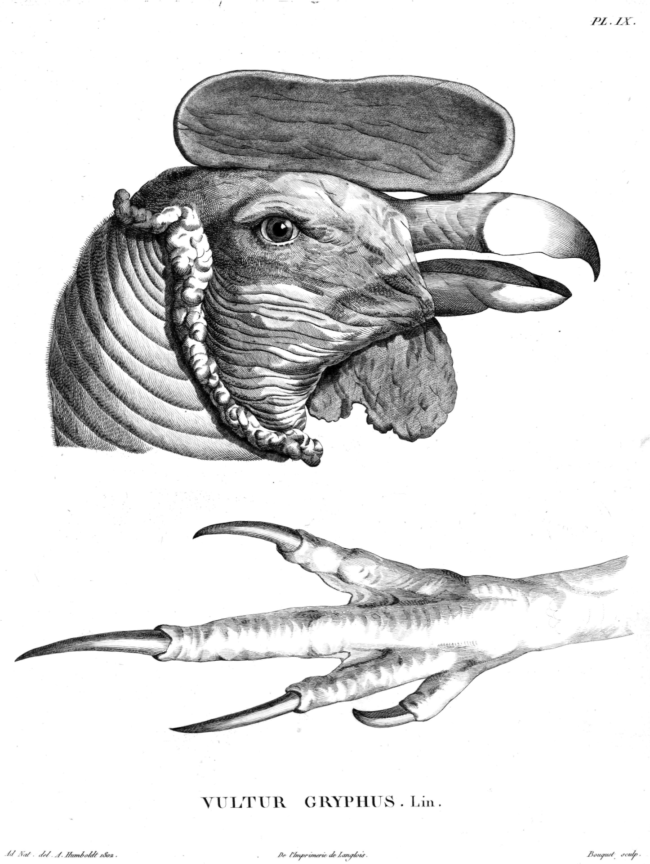

Humboldt’s depiction of an Andean condor. Public domain

No hardship deterred him from learning all that he could about Nature. At the end of five years living in the most remote parts of the world, he told a friend, “How I long to be in Paris.”

And so, when he finished his five-year exploration in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, after a quick stop to visit President Jefferson in 1804, he headed straight to Paris, bringing with him samples of 2,000 species of plants previously unknown to science — fully one third of all known species. Adulatory crowds and adoring scientists greeted him; the city welcomed him like a long-lost lover.

This was a scientist’s city. He shared ideas with the great naturalists George Cuvier and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (whose statue graces the entrance of the Jardin des Plantes); he talked astronomy and mathematics with Pierre-Simon Laplace (whose statue can be seen in Versailles); he taught alongside the chemist and balloonist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac; he talked politics with Simon Bolívar (whose statue is on the right bank of the Seine at the foot of the beautiful Pont Alexandre III).

Equestrian statue of Simón Bolívar in Paris. Photo credit: Emmanuel Frémiet / Wikimedia commons

Energized by the electric intellectual environment in Paris, he wrote and studied relentlessly, ferociously. He lectured at the Académie des Sciences, astounding its members with the breadth of his knowledge and his ability to unite disparate subjects. He planned dozens of books, visualized their elaborate illustrations, and followed the tangents of his voracious curiosity wherever they took him.

Despite feeling at home in Paris and being deeply connected to the scientific community there, Humboldt longed to travel… to be back in Nature. He left for Italy, went over the Alps, and ended up in his native Prussia. He had not planned on staying, but the Napoleonic Wars trapped him there and he despaired of ever being able to leave. When the King of Prussia asked him to go on a diplomatic mission to Paris, he jumped at the chance. When his ambassadorial efforts failed, he stayed in Paris, where he began the most fruitful writing period of his life. I suspect that he had no interest in diplomacy or in leaving Paris.

Humboldt in his library in his apartment, Oranienburger Straße, Berlin, by Eduard Hildebrandt. Magazin GEO. Public domain

He published (in French, 1810+) Views of the mountain ranges and monuments of the indigenous peoples of America, a title that demonstrates his conviction that nature and culture are intimately connected. He followed that (in French, 1811) with the Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain in which he reveals the abuses and injustices of Spanish imperial rule in South America and “argues that the destruction of nature will inevitably result in the destruction of culture.” In 1814, he published (in French) Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent during the Years 1799–1804. All the while, he was working on his 34-volume Voyage to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, from the years 1799–1804 (in French). I mention these titles not only to show his huge variety of interests, but to highlight that this is only a portion of his oeuvres, making him one of the most prolific writers of the French language in history.

Humboldt penguin, native to Chile and Peru. Photo credit: Adam Kumiszcza / Wikimedia commons

The world’s most accomplished intellectuals devoured these books, and the Parisian public adored him. He attended five Parisian salons every evening, staying for just a half an hour, talking rapidly about every subject from numismatics to volcanos. He lectured in public at every opportunity, bringing science to everyone. Crowds gathered around him when he went out to eat, and drivers were directed to take their clients to “chez Monsieur de Humboldt,” with no need for further directions. As Napoleon’s star faded with his second exile, Alexander von Humboldt became the most famous person in Paris.

Those who were fortunate enough to see the special exhibit at the Orsay in the summer of 2021 titled “The Origins of the World: The Invention of Nature in the 19th Century,” saw Humboldt’s portrait on display, as well as some handwritten notes from his expedition. The entire exhibition resonated with Humboldt’s influence, revealing the web of connections between art and science as humans wrestled with new ideas about evolution, dinosaurs, microscopic life, monsters, and human origins. For those who missed the exhibit, Gallimard published a magnificent volume (in English and French, with 246 images) with the same title as the exhibit.

The plaque in tribute to Alexander von Humboldt, on the wall of the house where he lived in Paris, 3 quai Malaquais. Medal by David d’Angers in 1831. Photo credit: Jebulon/ Wikimedia Commons

Today, there is a plaque honoring Humboldt on the wall of the house where he lived at 3, Quai Malaquais, just two blocks from today’s Académie des Sciences and the Institut de France, right next to the Arenthon Bookshop. It is an inadequate tribute to one of the world’s greatest and most passionate geniuses; but at least it is a reminder that he called Paris home.

[Note: Most of the information from this article comes from Andrea Wulf’s unmatched biography of Humboldt, The Invention of Nature. The book has been translated into numerous languages and even has its own Wikipedia entry].

Institut de France. Photo credit: Guilhem Vellut / Wikimedia commons

A 1959 Humboldt postage stamp from the Soviet Union. Public domain

Lead photo credit : Portrait of Alexander von Humboldt by Karl Joseph Stieler (1843). Public domain

More in Alexander von Humboldt, Napoleon, The smart side of Paris

REPLY