The World of Jules Verne, an Extraordinary Voyager

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

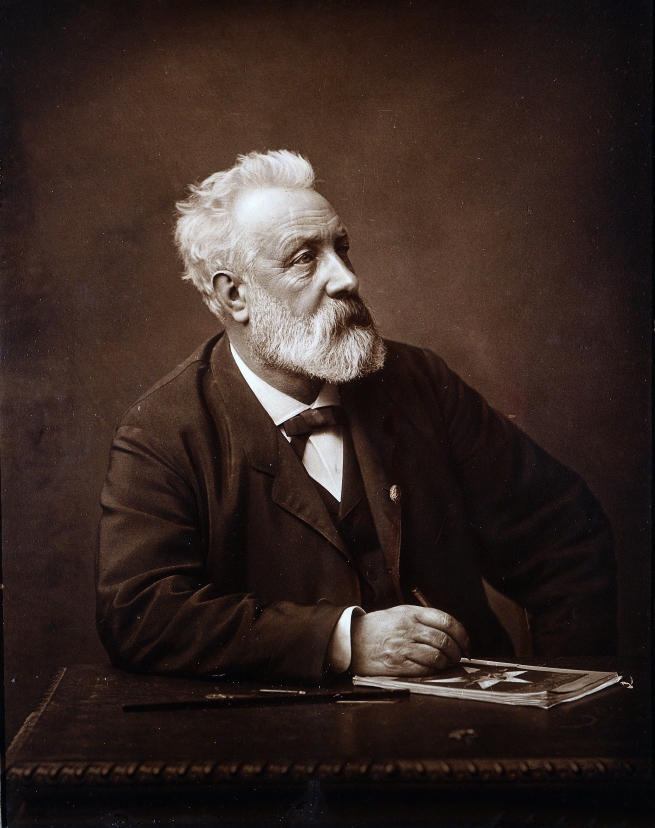

Jules Verne in 1892, photo: Wikimedia

“You like the sea, Captain?”

“Yes; I love it! The sea is everything. It covers seven tenths of the terrestrial globe. Its breath is pure and healthy. It is an immense desert, where man is never lonely, for he feels life stirring on all sides… The globe began with sea, so to speak; and who knows if it will not end with it?”

The world of Jules Verne was a remarkable one. Through the novels which comprise The Extraordinary Voyages, Les Voyages Extraordinaire, and the beautifully detailed illustrations which accompanied them, Verne remarkably envisioned what is common place to us nearly a century and a half later: hot air balloons, helicopters, airplanes, submarines, exploration of the moon, the north and south poles, and the use of hydrogen as an energy source. The names of his characters and inventions, such as Captain Nemo, Phileas Fogg, and the submarine Nautilus have become part of popular culture. Considered the “Father of Science Fiction”, Jules Verne was a true visionary.

Jules Gabriel Verne was born on February 8, 1828 on the small island of Feydeau, in Nantes, France, a busy maritime port city on the Loire River in the Upper Brittany region of Western France. The house at 2, quai Jean-Bart, where he spent the first 14 years– and the daily life of the islands, ports and boats– became the nexus of much of his work. It is said, when he was 11 years old, he clandestinely embarked aboard the three-masted La Coralie, bound for the Indies, but before the ocean-going vessel put to sea, it was intercepted by his father. The authenticity of this incident is far from certain, but his imagination and passion for travel and adventure proved undeniable.

At age six, Verne was sent to the first of a series of four boarding schools he would attend. His first teacher, the widow of a naval captain who had disappeared 30 years before, often told her students exciting stories about her missing husband being a castaway like Robinson Crusoe, who would eventually return from a desert island. This theme and others made an indelible impression on the young Verne. At the age of eight he was able to recite verses from memory in Greek and Latin.

While attending his last boarding school, in-between courses on rhetoric and philosophy, Verne began to write poetry. The poetry of happenstance was encouraged in his family – births, marriages, celebrations – and he was never without a pad and pencil. His father, a prosperous lawyer, sent him to Paris in 1847 to study law, hoping that as his first-born son, he would follow in his footsteps. Although he earned his law degree, Verne rejected his parents’ middle-class respectability, refusing his father’s offer to open a law practice in Nantes, because he was secretly planning a literary career.

A young Jules Verne in 1856, photo: Wikimedia

Inherently drawn to the literary and theatrical scene in Paris, Verne lived a Bohemian life. He frequented many Parisian salons and befriended a group of artists, and writers that included Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo, both of whose work he respectfully emulated. It was through his friendship with Dumas and Dumas son, that his first play, Broken Straws, was produced in 1850, reaping a modicum of success. Despite continued parental pressure, Verne continued to write and in 1852 he took a poorly paid position as secretary of the Théâtre-Lyrique, in order to have a platform to produce two more of his pieces, Blind Man’s Bluff and The Companions of the Marjolaine.

Verne tried different forms of writing, adding comedies, operettas and short stories to his repertoire. His short stories were particularly good and were frequently published in the popular magazine, The Museum of Families, which was an illustrated French literary journal founded by Émile de Girardin. Surrounded within its pages by illustrious writers such as Dumas and Balzac, Verne couldn’t help but feel fame and fortune was within reach.

In 1856, Verne met, fell in love with, and the following year married, Honorine de Viane, a young widow with two daughters. Realizing he needed a stronger financial foundation for his new family, he began working as a stockbroker alongside his wife’s brother. Membership in the Paris Exchange did not interfere with his daily writing schedule, however, because he adopted a rigorous timetable, rising at five o’clock in the morning in order to put in several hours researching and writing before beginning work at the Bourse. In 1857, he published his first book, The 1857 Salon.

Verne’s personality was contradictory, not terribly unusual for a writer. Capable of extreme conviviality, he was equally happy alone in his study or when sailing the English Channel in a converted fishing boat. Verne and his wife made approximately 20 sea voyages to the British Isles. These journeys inspired him to pen Backwards to Britain; however, the novel wasn’t published until 1989, 84 years after his death. In 1861, the couple’s only child, Michel-Jean-Pierre Verne, was born. It was in this period that Verne met the noted geographer and explorer Jacques Arago, who continued to travel extensively despite his blindness (he had lost his sight completely in 1837). The two men became good friends, and Arago’s innovative and witty accounts of his travels led Verne toward developing an new genre of literature called “travel writing.”

By 1862, Verne’s literary career had failed to garner major attention, but his luck changed with the introduction to editor and publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel. Hetzel encouraged Verne to develop his evolving style- “Roman de la Science”, adventure narratives within the framework of scientific research. In 1863 Hertzel published Five Weeks in a Balloon, or, Journeys and Discoveries in Africa by Three Englishmen, to wide acclaim and Jules Verne the novelist was officially born. Hetzel, who previously rejected Backwards to Britain because he felt it was more cerebral and less exciting, had made the right decision. It was the first in a series of 54 extraordinary journeys by air over central Africa, at that time largely unexplored. Verne retired from stockbroking and devoted himself full time to writing. Years later he would say, “I wrote Five Weeks in a Balloon, not as a story about ballooning, but as a story about Africa. I always was greatly interested in geography and travel, and I wanted to give a romantic description of Africa. Now, there was no means of taking my travelers through Africa otherwise than in a balloon, and that is why a balloon was introduced.”

In 1864, Hetzel published The Adventures of Captain Hatteras, which centered on an expedition to the North Pole (not actually reached until 1909 by Robert Peary), and A Journey to the Center of the Earth which described the adventures of a party of explorers and scientists who descend the crater of an Icelandic volcano and discover an underground world. That same year, Verne’s Paris in the Twentieth Century was rejected for publication by Hertzel. “No one will believe your depictions of skyscrapers, gas-fuelled cars and mass transit systems, because they are too far fetched.” An interesting historical aside to this particular book is that Verne kept the unpublished manuscript hidden in a large bronze safe. It was discovered by his great-grandson after the sale of the family home.

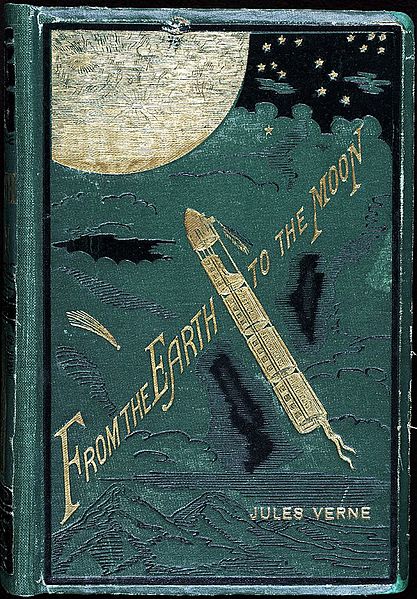

From the Earth to the Moon, photo: Wikimedia

In 1865 Verne was back in print with From the Earth to the Moon, which described how two adventurous Americans, joined by a Frenchman, arrange to be fired in a hollow projectile from a gigantic cannon that lifts them out of Earth’s gravity field and takes them close to the moon. Verne not only pictured the state of weightlessness his “astronauts” would experience during their flight, but he had the remarkably prescient idea to locate their launching site in Florida, where nearly all of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) launches take place today. Two years later, Hetzel published Verne’s Illustrated Geography of France and Her Colonies. That same year Verne traveled to the United States, and though he only stayed a week, he managed a trip up the Hudson River to Albany, then another to Niagara Falls.

In 1870, Hetzel published Verne’s masterpiece, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, relating the voyages of the submarine Nautilus, built and commanded by the mysterious Captain Nemo, one of the literary figures in whom Verne incorporated many of his own character traits. By this point, his works were being translated into English, and he could comfortably live on the money made from his writing. Although he was enjoying immense professional success, he began experiencing discord in his personal life. He sent his rebellious son to a reformatory school, and a few years later he was shot in the leg by his nephew, Gaston, leaving him with a limp for the rest of his life. A week later his editor and publisher, Hetzel, died, and the following year his mother passed away. A man possessed, Verne continued to travel and write, his writing taking a darker tone with books like The Purchase of the North Pole and Master of the World, the later warning of the social dangers wrought by uncontrolled technological advancements.

Beginning in late 1872, the serialized version of Verne’s famed Around the World in Eighty Days appeared in print. The story of Phileas Fogg and Jean Passepartout took readers on an extraordinary world tour at a time when travel to exotic lands was seductively alluring. In the century since its original debut, this magical work has been adapted for the theatre, radio, television and film.

Verne remained prolific throughout the decade, penning, The Mysterious Island, The Survivors of the Chancellor, Michael Strogoff, and Dick Sand: A Captain at Fifteen, among many others. Years later his written successes became triumphant when adapted for the stage. Around the World in Eighty Days, Michael Strogoff and The Children of Captain Grant were spectacularly staged productions that filled the theatres of the Châtelet and Porte Saint-Martin in Paris, every night for months.

Jules Verne’s tomb in the cemetery at Amiens, photo: Wikimedia

In 1888, Verne moved to the northern French city of Amiens, Picardie. He was elected a councillor of Amiens, a position he served faithfully for the next 15 years. He also continued to travel and write. His last publication was Master of the World in 1904. After developing diabetes, Jules Verne died at his home on March 24, 1905, but his literary output didn’t end with his death. His now-reformed son assumed control of his father’s uncompleted manuscripts, finishing and publishing them himself. The Lighthouse at the End of the World in 1905, The Golden Volcano in 1906 and The Hunt for the Golden Meteor in 1908.

Verne’s novels have had an extensive influence on scientists and writers from Wernher von Braun to Antoine Saint-Exupéry. In the words of science fiction writer, Ray Bradbury, “We are all, in one way or another, the children of Jules Verne.”

Jules Verne is buried in La Madeleine Cemetery in Amiens, Picardie, France. A massive marble statue of a man emerging from the earth reaching towards the sky adorns his grave.

Lead photo credit : Jules Verne in 1892, photo: Wikimedia

REPLY

REPLY