Down and Dirty: Explore the Paris Sewers at Musée des Égouts

“The sewer is the conscience of the city,” prophesied Victor Hugo with bizarre fascination in his magnum opus, Les Misérables, first published in 1862. But if Paris is a city rhapsodized for its grandiose exterior, you’d be forgiven for not having explored the recently renovated Musée des Égouts de Paris, a quirky museum which, rather than celebrating the visible, transports you into Paris’s murky depths.

Indeed, underneath Paris lies another Paris – a Paris which sighs beneath the weight of a city replete with superlatives, but which nonetheless has plenty to offer. Acting as air-raid shelters during the Nazi Occupation and commandeered by the Resistance as first-aid stations during Paris’s liberation in 1944, history winds its way down the tunnels of Paris’s sewers, dormant underneath the buzz of life above it, waiting to be discovered by those who look beyond the quotidian.

Exterior of Musée des Egouts. @ Olivier Placet

The Musée des Égouts de Paris in the 7th arrondissement, just around the corner from the Eiffel Tower, takes you through the history of the sewers in the very place where all the action happens.

Although the network is labyrinthine in its nature, art-deco style road signs within the sewers correspond to those which adorn Paris’s street corners, helping the vidangeurs to orientate themselves within the maze of passages. While rats are unwelcome visitors around the Sacré-Cœur and the Marais, in the égouts, rats are a worker’s best friend. The sewer workers rely on their furry friends to inform them about which areas have potentially fatal levels of noxious gases, indicated by the rodents running in the opposite direction. Our tour guide explained that the rats we see above ground, who are unafraid of the presence of humans, are a rotund species, thanks to the scraps of croissant crumbs dropped by peckish Parisian commuters. The species found in the sewers, however, are far smaller and terrified of coming face to face with a sewer worker.

But the sewer network we can see today has undergone a significant makeover since it was originally built in 1370 by Hugues Aubriot, Provost of Paris under Charles V. The early 19th century saw a period of seismic change in Paris, a metropolis already reeling from the political upheaval of the French Revolution. The population of Paris had doubled since 1815, allowing all manner of plagues and pestilence to spread around the city. Unsatisfied with the overcrowded and unsanitary nature of the French capital, Napoleon‘s Prefect of the Seine, the much feted and simultaneously highly controversial figure, Baron Haussmann, orchestrated an urban renewal program of an unprecedented scale in any other Western metropole. Haussmann’s urban planning aimed to tackle overcrowding and the growing population by expanding the boundaries of the city, adding an additional eight arrondissements onto the existing dozen.

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809-1891), Prefect of Paris, urbanist of the Napoleon III’s Paris, Public Domain

The renovation program – hugely controversial for its time – saw the mass demolition of buildings and avenues, making way for much of what characterizes the modern-day Île-de-France. This included four large green spaces, as well as the tree-lined boulevards and attractive wide thoroughfares, carefully and meticulously planned out, coaxing the unassuming eye towards Paris’s most breathtaking monuments and museums.

Built between 1853-70, Haussmann’s underground sewage system, a dense labyrinth of pipes, sewers and tunnels, updated the antiquated version. Previously, containers of waste were picked up each night by the vindangeurs who carried it to waste dumps outside of the city. The tunnels were extremely narrow and cholera epidemics, which had killed over 20000 Parisians, were rife, due to the unsanitary water and lack of waste management which lay stagnant in open gutters. The health risks were so severe that the vidangeurs were – and still are – permitted take retirement 10 years early.

Displeased with the mismanagement of the sewers, under Haussmann’s ingenuity, the city’s underground system was completely reconstructed, creating a complex network of sewers which modernized the city’s archaic sanitation systems, flushing sewage downstream into the Seine. “These underground galleries would be the organs of the metropolis and function like those of the human body without ever seeing the light of day,” Haussmann wrote in 1854, boasting about the efficiency of his work. “Pure and fresh water, light and heat, would circulate like the diverse fluids whose movement and replenishment sustain life itself.”

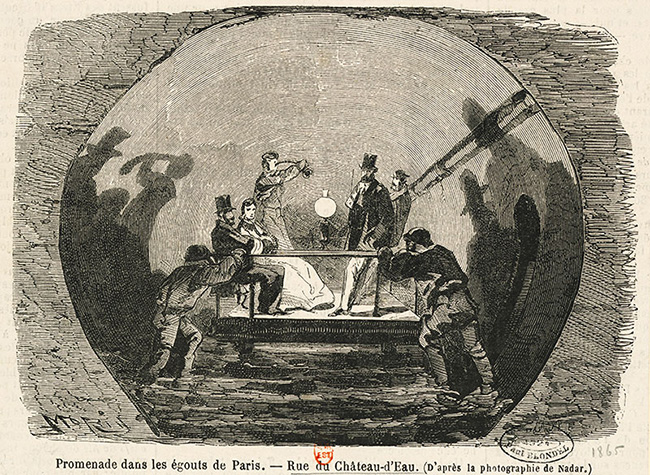

Promenade dans le égouts de Paris. Rue du Château-d’Eau, Illustration by Morin after Nadar’s photography, 1865

Significantly expanding the tunnels in both height and width, Haussmann’s feat of engineering created a deft and agile network that became a hallmark of France’s industrial prowess. As a result, mortality rates dropped drastically, and rainwater was treated and cleaned so that, for the first time, there was a distinction between potable and non-drinking water. The renewed system also provided gas for heat and lights to illuminate Paris, literally giving it its nickname, ‘The City of Light’, a truism which holds to this day.

Want to see it for yourself? Discover more about the profession of the once overwhelmingly male vidangeurs, as well as the influence of Haussmann’s sewers authentically represented in Disney’s Ratatouille: the museum has something for everyone. En profitez-vous !

DETAILS

Musée des Égouts de Paris (Paris Sewers Museum)

Esplanade Habib Bourguiba, Pont de l’Alma, 7th

Tel: +33 (0)1 53 68 27 84

Regular ticket price is 9 euros.

Open Tuesday to Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Last admission is 4 p.m.

The duration of the visit is 45 min to 1hr15.

Wear comfortable, flat shoes and dress warmly; the year-round temperature is 13°c.

Lead photo credit : Inside Musée des Egouts. @ Olivier Placet

More in architecture, history, Museum, Sewer Museum

REPLY

REPLY