Flâneries in Paris: Explore the Place Saint-Sulpice

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 13th in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

La Place Saint-Sulpice is immediately imposing. The square is framed by chestnut trees and the Church of Saint-Sulpice forms a magnificent backdrop along one side. Cars and buses pootle around its edges, Parisians cross it purposefully on their way north to Boulevard Saint Germain or south to the Jardin du Luxembourg, tourists linger to take pictures of the elegant central fountain where four bishops nestle in alcoves under a domed roof. Watched over by enormous sculpted lions, they seem to be listening to the water cascading down two stepped levels into the pool below.

St Sulpice Fountain detail, courtesy of Marian Jones

At first sight, the fountain seems rather impractical, as if it were not designed to drink from. In fact, it really wasn’t and for a very specific reason. In the 1830s, the Préfet of the Seine masterminded a huge project, bringing clean water to Paris through 1700 small fountains. In addition, perhaps in celebration of his achievement, he oversaw the building of a small number of huge, decorative fountains, including this one and others at Place de la Concorde and the Fontaine Molière in the 1st arrondissement. So, this one is simply here to be admired. And it is lovely: a cooling promise on a hot summer’s day, a frosty beauty in winter.

St Sulpice fountain, courtesy of Marian Jones

The fountain is the subject of a linguistic joke which has been told down the generations. Being a French joke, it’s quite sophisticated, but I hope anglophone readers will enjoy it too! The fountain is known as les points cardinaux (the four points of the compass) because it is four-sided. The word cardinaux also means “cardinals” and the joke – and this is where you can allow yourself a wry smile – is that none of the four bishops whose statue is here was ever a cardinal. There’s even an extra “layer,” because point can mean “not,” so the fountain’s title translates as “not cardinals.” I imagine parents telling their teenagers this as they pass and wonder if it’s perhaps a joke which was funnier in the 19th century.

The square – La Place Saint-Sulpice – was the subject of a literary experiment in October 1974. The author Georges Perec stationed himself there for 24 hours – actually three periods of eight hours – and wrote a minute-by-minute description of everything that happened. The resulting 60-page book was published in English under the title An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris and included such entries as “pigeons fly around the square,” “a 70 bus passes” and “the church bell stops.”

Place Saint Sulpice, église et fontaine. Credit: Guillaume2294 / Wikimedia commons

Why not replicate his experiment I thought, and note everything which happens in – the 21st-century attention span being much shorter – a minute? So I did. I can report that the pigeons are still there, and that the people who passed me by in those 60 seconds included a couple pushing small-wheeled suitcases who stopped to consult their phones (newly arrived city-breakers checking the map?), a lone dog making his way purposefully across the square, several joggers and a tiny lady dressed head to foot in black, except for luminous pink trainers. Her minuscule dog was dressed, bien sûr, in a matching black coat. And then, just as the last seconds were ticking by, came an interruption to my thoughts from a stout man with a shambling air. “Shall I take your photo for you?” he asked, pointing at my camera. It was a reminder to keep my wits about me, even in this elegant square.

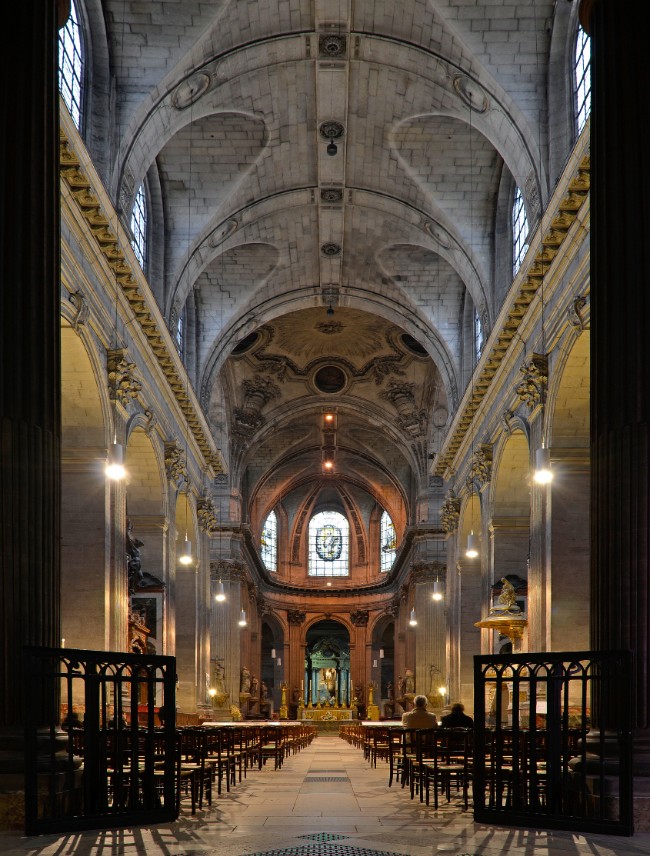

Saint-Sulpice is a Parisian institution, the city’s second largest church after Notre-Dame and currently serving as its cathedral while Notre-Dame is being repaired. Even the outside has stories to tell. I looked up at its “twin” towers, knowing I would find that they did not match: one was never completed because the revolution got in the way, although the faithful made sure a rejection of the era’s atheism was carved over the front portal. “The French people,” it reads, “believe in the supreme power and the immortality of the soul.” My translation sounds a bit Dan Brown – did you know that two chapters of the Da Vinci Code are set in Saint-Sulpice? – but in French the “supreme power” is, quite simply, God. A statement of fact, if you will.

The nave of Saint Sulpice. Credit: Selbymay / Wikimedia commons

I was keen to see inside the church where Baudelaire was baptized and Victor Hugo made his marriage vows. As so often with these huge churches, there’s so much to absorb that it seems best to wander and just take what comes. A cavernous interior opened up, pillars and vaults stretched down to the distant altar. Where to begin? I knew that the first side chapel on the right contained three huge Delacroix paintings, so I went to have a look.

One of the Delacroix murals in St Sulpice church, courtesy of Marian Jones

Being familiar with “Liberty Leading the People,” with its revolutionary urgency, maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised to find all three works had combative themes, even in this holy setting. On the ceiling, Jacob pits all his strength against an angel, while on the walls down below are two more enormous fight scenes based on biblical stories. In one, the Syrian minister Heliodorus, sent to the Temple of Jerusalem to confiscate riches, is overcome by guards on horseback. On the opposite wall, Saint Michael wins a celestial battle against – as the Book of Revelation puts it – “the enormous dragon, the ancient serpent, the devil, or Satan as he is known.” It’s good versus evil, or maybe faith versus doubt, and stirring stuff.

Saint Sulpice as seen from the Tour Montparnasse. Credit: David McSpadden / Wikimedia commons

Further into the church were more spots for contemplation. The chapels dedicated to St Anne and St Louis were built in the 1840s to honor a promise made 200 years earlier to Anne of Austria, mother of Louis XIV. When she laid the first stone of the building, she asked that chapels should be included in memory of her and her son and today you can admire the marble statues which decorate them. St Louis is dispensing justice under an oak tree, as history tells us he did when he was King Louis IX.

A cloaked St Anne teaches the young boy by her side, perhaps intended to evoke the guidance Anne of Austria gave her young son who became king at the age of four? But I’ve read descriptions of her kneeling before him in deference to the child’s superior status and frankly, given what we know about the adult Louis, I find the stories of Louis the child-tyrant more believable than the sculpture of Louis, the acquiescent young learner.

A statue in St Sulpice, courtesy of Marian Jones

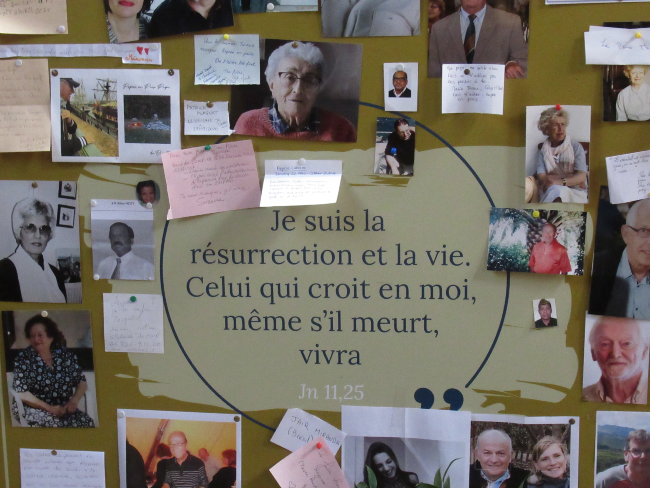

Among all the reminders of things past was an exhibition which showed Saint-Sulpice in its role as a church for its local community today. The last side chapel I passed on my way out was set aside as a Mémorial pour les victimes du Covid 19. A poster explained that anyone, church member or not, could leave photos, messages or flowers in memory of someone lost to covid or perhaps write something in the memorial book. The host of faces pinned to the surrounding display boards looked back at me: a man in a peaked cap sitting beside his boat on a riverbank, a smiling granny in a pink cardigan, a number of photos showing two happy faces. Did they both die, or has someone left a favorite photo of themselves with a loved one?

St Sulpice Covid Memorial, courtesy of Marian Jones

I’d planned Saint-Sulpice to be just the starting point on a walk through Saint-Germain-des-Prés, not realizing how much there would be to linger over in the square and the church. It was nearly lunchtime and the nearby Marché St Germain, which I have seen described as “the poshest market in Paris,” seemed like a good idea. So, I set off round the corner in search of les belles arcades described on their website, under which I would find a rôtisserie, an oyster bar and lots of upmarket foodie shops. My planned flânerie through more of St Germain would be a treat for another day.

Lead photo credit : Eglise Saint-Sulpice. Credit: Mbzt/ Wikimedia commons

More in Churches in France, churches in Paris, Delacroix, Flaneries, Flâneries in Paris, Saint Sulpice, saint-sulpice

REPLY

REPLY