Was Émile Zola Murdered? And the Dreyfus Affair that Never Went Away

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

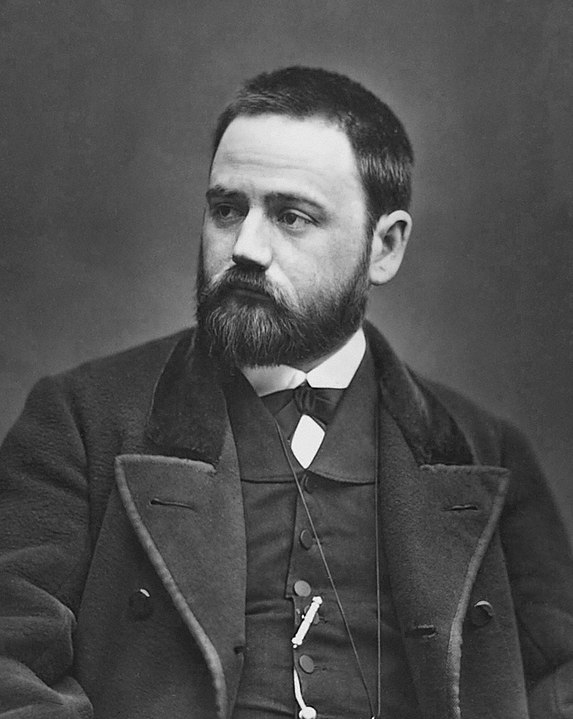

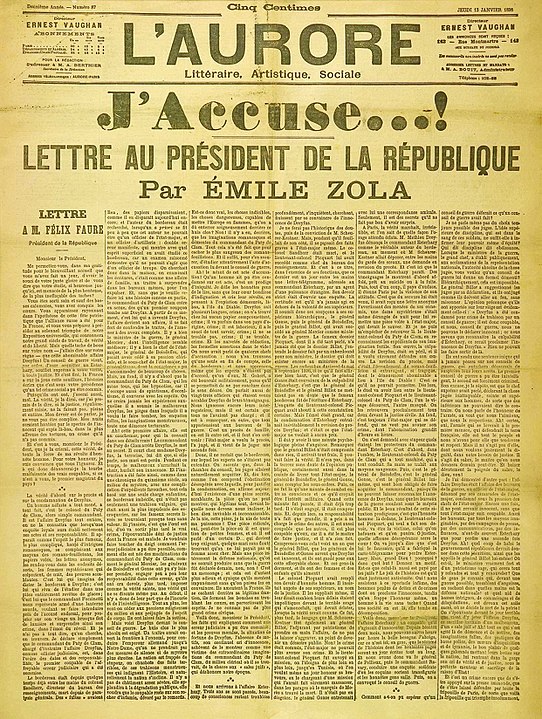

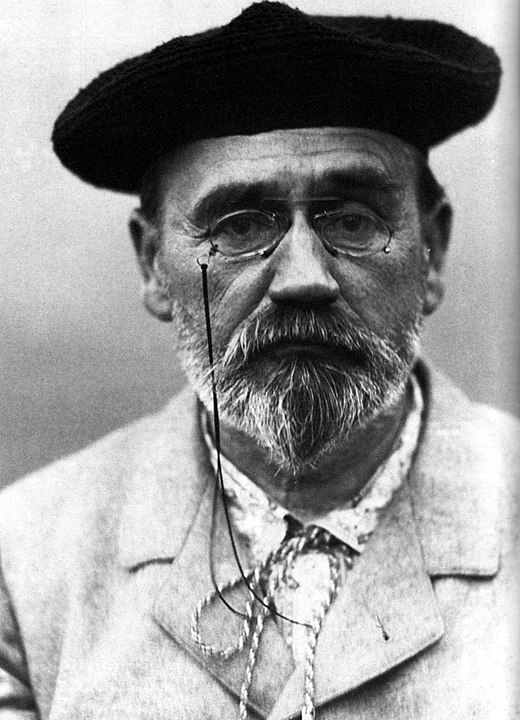

Almost a century ago on September 29th, 1902, Émile Zola died in the early hours of the morning in his house at 21 bis Rue de Bruxelles in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. Zola had lived there with his wife Alexandrine from 1889 until his death, and it was where he wrote his infamous “J’Accuse…!” on January 12th, 1898.

It was a cold, wet night and a coal fire had been lit in their bedroom. As always, the windows were closed and due to numerous death threats after the publication of “J’Accuse…!” on the front page of the newspaper L’Aurore, their bedroom door was locked.

They were both still awake at 3 am, feeling unwell, but Zola believed the cause to be indigestion and dissuaded Alexandrine from calling the servants.

Zola early in his career (C) Étienne Carjat – Museum of Photographic Arts, Public Domain

It proved to be a fatal decision. They were both being slowly poisoned by carbon monoxide fumes from the coal fire. Zola had attempted to rise from the bed but had fallen to the floor and Alexandrine had lost consciousness still lying in bed. Six hours later at 9am, the servants forced the bedroom door. Zola, despite 20 minutes of artificial respiration by a doctor, could not be saved but Alexandrine, still unconscious, recovered later in a clinic.

The immediate and widespread consensus was that Zola had been murdered. With his article “J’Accuse…!” and his vociferous attempts to clear Dreyfus, Zola had made many powerful enemies, both in the military and with the nationalist right who were so often rabidly anti-semitic.

Front page cover of the newspaper L’Aurore for Thursday 13 January 1898, with the open letter J’Accuse…!, (C) Émile Zola – Scan of L’Aurore, Public Domain

In an attempt to calm down speculation, an inquest was ordered and specialists called to inspect the fire and chimney in Zola’s bedroom. Despite fires being lit, guinea pigs surviving being left in the room overnight, nothing significant was found, and the coroner’s verdict proclaimed that Zola had died of natural causes.

A death bed confession in 1927 by an anti-Dreyfusard stove fitting contractor, was published in a French newspaper in 1953. In his confession he stated that while fixing the neighboring roof, he and his workmates had deliberately blocked the chimney of Zola’s house, removing the blockage the following morning. Many of Zola‘s biographers have accepted this more than plausible version of Zola’s death, but as in so many conspiracy theories, the definitive truth is unlikely to ever be known.

Luc Barbut-Davray, Portrait of Zola, Oil on Canvas, 1899 (C) Dr. Michael Pearce, CC BY-SA 4.0

Zola had been controversial long before “J’Accuse…!” but this open letter to French President Félix Faure, accusing various high ranking officers and indeed the War Office itself of concealing the truth and unlawfully imprisoning Dreyfus, caused outrage. Outrage, predictably among the far right nationalists and militarists who often had anti-semitic leanings and were convinced of Dreyfus’s guilt, but also among the left-wing anti-militarist public, who were just as convinced of his innocence.

Zola used the phrase “J’accuse” eight times. To accuse, foremost, Lt. Col. du Paty de Clam, as “the diabolic creator of the miscarriage of justice,” General Mercier of complicity, General Billot of concealing the absolute proof of Dreyfus’s innocence, General de Boisdeffre and General Gonse of complicity, General de Pellieux and Major Ravary of conducting a fraudulent and monstrously biased inquiry, the three handwriting experts, the War Office, specifically for conducting an abominable campaign in the press to mislead public opinion and cover up their wrong doing, and last but not least, the court martial, of committing the judicial crime of acquitting a guilty man, Ersterhazy, with full knowledge of his guilt.

Le colonel du Paty de Clam (C) Unknown, Public Domain

Zola had continued in his letter that he was aware that in making these accusations he was making himself liable to prosecution for libel and dared them to bring him before a court of law and investigate in the full light of day. “I am waiting,” he ended.

The Dreyfus affair has been well documented. Alfred Dreyfus was a Jewish artillery Captain in the French army. In September 1894 he was suspected by French intelligence to be passing military secrets to the German army. The verdict appeared to be based on nothing more than anti-semitism among senior officers, but nevertheless, without any direct evidence, Dreyfus was court-martialed, ceremoniously stripped of his rank, his sword snapped, convicted of treason and sent to the notorious Devil’s island in French Guiana.

And then began one of the most shameful cover-ups in French military history.

“The traitor: Degradation of Alfred Dreyfus, degradation in the Morland Court of the military school in Paris” (C) Henri Meyer, Public Domain

A certain Lt. Col Georges Picquart discovered evidence that implicated another officer, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy and informed his superiors. Determined that Dreyfus’s verdict was not overturned, Major Hubert-Joseph Henry forged papers to confirm Dreyfus’s guilt and Picquart was posted to Africa. Picquart’s lawyer took up the case and communicated the findings to the Senator Auguste Scheurer-Kestner. As further evidence was brought forward, the military was brought under pressure to court-martial Esterhazy, but even this was held “in camera.” Not only was Esterhazy acquitted, but Picquart was detained on charges of violation of professional secrecy.

But covering up the evidence, acquitting a guilty man and imprisoning an innocent one, was a story that could not be quieted. L’Aurore decided that Zola’s letter would be run on the front page of the newspaper. L’Aurore was owned by Georges Clemenceau who later became Prime Minister of France from 1906-1909 and later from 1917-1920. Clemenceau was an inspired leader during WWI participating in the Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Paris. Clemenceau was so convinced of Drefus’s innocence that he carried on an eight-year battle in both L’Aurore and also his other newspaper, La Justice, to support him. The other owner of L’Aurore was the journalist Ernest Vaughan.)

Gravestone of Émile Zola at cimetière Montmartre; his remains are now interred in the Panthéon. (C) Donar Reiskoffer, CC BY-SA 3.0

Zola’s moral outrage had both divided public opinion in France and had stained its reputation, causing even more unrelenting, bitter and unforgiving hostilities against Jews and Zola who had defended one so publicly. L’Aurore was attempting to combat an increasingly virulent anti-semitic press in newspapers such as La Libre Parole and La Croix which were only too happy to expound Dreyfus’s guilt with scurrilous racist diatribes.

Zola was indeed brought to trial for criminal libel on February 7th, 1898, convicted 16 days later, and removed from the Legion of Honor. The judgement was overturned on a technicality but a new suit was pressed against him in July. This time Zola heeded his lawyer’s advice and fled to England where he stayed until the following June. The Dreyfus affair had not gone away in Zola’s absence; Major Henry’s forgery was discovered and admitted to in August 1898 and Dreyfus’s original court martial was referred to the Supreme Court for review. The Supreme Court ordered a new military court martial and annulled the original verdict. Astonishingly, despite the furore that had continued unabated, on September 1899, Dreyfus was again convicted. Zola was back in France when Dreyfus demanded a retrial. The government, eager to put an end to the public disquiet, instead offered Dreyfus a pardon. Although not an exoneration, Dreyfus accepted.

“M. le Lieutenant-Colonel Henry.” (Dixième audience du procès Zola) (C) Louis Rémy Sabattier, Public Domain

(It wasn’t until 1906 that Dreyfus was finally exonerated and reinstated as a major in the French Army. He died in 1935 having served through the entirety of WWI, ending his service with the rank of lieutenant colonel.)

Later the same month, in 1899, an amnesty bill was passed which “covered all criminal acts or misdemeanours in the Dreyfus affair,” effectively protecting all those who gave evidence against Dreyfus, but also indemnifying Zola and Picquart. Zola condemned the bill, but stated that, “The truth was on the march, and nothing shall stop it.”

It was easy to believe, with so many enemies snapping at his heels, that Zola had not died a natural death.

Zola’s defense of the innocent, railings against injustice and the establishment, had ineluctably taken root in the deep, fertile ground of his own family’s misfortunes. Emile Zola’s life-long sense of burning injustice had begun in childhood.

Zola was born in 1840 to an Italian father and French mother. Zola’s engineer father had designed a damn under Mont Sainte-Victoire for channeling water to Aix-en-Provence, so it can be assumed that the family were living if not an affluent life, then certainly a comfortable one.

Zola’s father died on the eve of construction and control of the Zola Canal Co. fell into the hands of swindlers. The consequences were dire for Madame Zola who, left with worthless shares, spent years in futile litigation. Years that colored Emile’s adolescence.

In 1858, 11 years after Zola’s father’s death, Zola and his mother, existing on her tiny pension, returned to Paris.

Zola’s mother had hoped for a career in law for her son, but now reunited with his old friend Paul Cezanne in Paris, Zola showed little interest in either passing the Baccalaureat or in a legal profession. (Zola loudly condemned the decision of the Academie des Beaux-Arts when they rejected not only Cezanne’s paintings but also those of other Realist painters.)

He began writing literary and art reviews for newspapers, soon moving on to politics, poems, short stories and novels. Zola’s output was prodigious, but it was his sordid autobiographical novel, La Confession de Claude, published in 1865, that attracted police attention and confirmed his style of writing as “naturist.” His first major novel, Thérèse Raquin, was published in 1867, after which he began the monumental series, Les Rougons-Macquart, which followed the lives of the members of two fictional families living during the Second French Empire (1852 – 1870) in 20 novels. The families are divided by class and education; the bourgeoisie, the blue collar worker, the priest, the alcoholic, the prostitute, are all encompassed in the series written roughly one per year from 1871 – 1893.

Claude’s Confession by Émile Zola, Stephen R. Pastore (C) Goodreads

It was the publication of L’Assommoir in 1877, however, that established Zola as an eminent and highly influential French writer, ensuring personal wealth, and recognition among his peers which included Victor Hugo and Guy de Maupassant. In 1901 and then in 1902, Zola was nominated for the first and second Nobel Prize in Literature, although he was never elected to L’Académie française.

Zola’s personal life was complicated. His wife, Alexandrine, was his mistress for five years before they married in 1870. They remained married, but childless, until Zola’s death. In 1888, Alexandrine hired a seamstress, Jeanne Rozerot, 27 years younger than Zola, who lived with them in their splendid house in Medon. Zola fell in love with Jeanne who had two children by him. Alexandrine discovered their affair in 1891 when Jeanne had moved to Paris with Zola’s children. The marriage managed to survive and Zola was able to participate more in his children’s lives.

The same afternoon that Zola died and Alexandrine was still recovering in the hospital, she contacted Jeanne Rozerot and Zola’s children, Denise 13 years old and Jacques aged 11, who came to the Paris house for the first time.

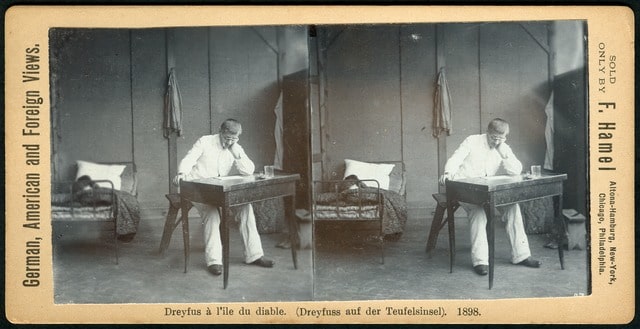

Alfred Dreyfus in his room on Devil’s Island in 1898 (C) Unknown, Public Domain

Zola’s body was lying in an open coffin, surrounded by flowers. One of the first people to pay their respects was Alfred Dreyfus. On October 5th, a crowd of more than 50,000 came out for the funeral at the Montmartre Cemetery. They included Anatole France, Dreyfus, government ministers, freemasons, and a delegation of miners. (Germinal, the 13th novel in the Rougons-Macquart series, was considered one of Zola’s finest novels with its uncompromising, often brutal story of a coal miner’s strike in northern France. It depicted the miners’ poverty and oppression and their worsening living conditions.)

Soldiers presented arms as the hearse passed.

In 1908, Zola’s remains were exhumed and taken across Paris to be interred in the Pantheon, the highest honor that could be bestowed on only the finest citizens of France. The following morning, the President attended the reburial. Zola was laid to rest next to Victor Hugo in the crypt.

And here the story should end. Dreyfus exonerated and Emile Zola, his champion, laid to rest.

But more than a century after Dreyfus was cleared, the far right in France are still questioning his innocence. In particular, Éric Zemmour, the Jewish, anti-immigrant TV pundit, who may still declare his candidacy in the French Presidential elections, is attempting to re-write history and sow discord. He has defended Pétain who collaborated with the Nazis in WWII, stating that he saved the lives of Jews rather than assisting in their deportation to the death camps. Of Dreyfus, Zemmour said that “this affair was murky,” and “his innocence was not obvious.”

Emmanuel Macron (C) CC BY 2.0

President Emmanuel Macron disagrees. In October, he personally inaugurated the first museum dedicated to the Dreyfus affair. It is fittingly exhibited in Emile Zola’s house in Médan.

Over the last century, countless academics, historians and researchers have explored every piece of evidence in the so-called Dreyfus Affair.

They unanimously agreed on the innocence of Alfred Dreyfus.

As Zola said in “J’Accuse…!”: “The truth was on the march, and nothing could stop it.”

Lead photo credit : Portrait of Émile Zola. Unknown author. Public Domain

More in Affair, history, Paris, Writer

REPLY