Émile Zola: French Writer and Social Justice Advocate

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

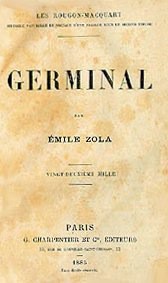

Fill in your credentials below.

The story opens on a pitch-black, starless night in March. A solitary man, starving in threadbare trousers, hands numb from biting winds, trudges along the barren landscape that separates him from certain destitution and the possibility of future hope. The tale that unfolds in this undisputed masterpiece by Émile Zola portrays the harsh and desperate life of France’s late-19th century coal-miners. But it ends—as its title, Germinal, suggests—recalling the name of the 7th, springtime month of the Republican Calendar—with a hint of better times to come. An immediate sensation, an inspiration for reformist causes throughout Europe, a symbol for the working classes determined to throw off the stranglehold of oppression, Zola’s tour de force was a clear sign that the changes germinating beneath the surface of French society for decades were finally ripe for flowering.

Zola the writer and his sense of duty to record reality

In 1867, Émile Zola (1840-1902), onetime-clerk-cum-journalist with a published novel, Thérèse Raquin, already under his belt, embarked on a literary project to document the epic journey of two branches of a single family over five generations. Starting with the common ancestor, Adelaïde Fouque, born in 1768, the story follows the hard-working, successful, and respectable Rougons—descendants of her marriage—alongside the unstable, alcoholic, often criminally violent and sometimes artistically exceptional Macquarts—the illegitimate progeny of her tempestuous lover.

Zola believed that the job of the novelist, like that of the scientist, was to observe and record reality with the sole aim of demonstrating truth. He had no use for literature based on fictitious characters symbolic of this or that human vice or virtue. He sought, instead, to describe characters that, like humans themselves, were products of their genetic predisposition and the milieu in which they lived.

Zola’s novels were testimonials of the times that captivated France

The 20-book result of his 26-year effort, of which Germinal was the 13th installment, was therefore two-pronged: With Les Rougon-Macquart: L’Histoire naturelle et sociale d’une famille sous le Second Empire, Zola not only traces the influence of heredity and environment on human thought and action, but he also paints a complete and splendidly-detailed portrait of life at every level of society during the reign of Napoleon III.

In Le Ventre de Paris (1873) we are taken on an exquisite journey to Paris’ once famous food market, Les Halles, now a place of legend. In La Débâcle (1892) we experience the horrors of the Franco-Prussian War and take a front row seat to the emperor’s downfall, an event Zola surely applauded. Au Bonheur des Dames (1883) gives us a snapshot of middle-class Parisian life under the emperor; while Nana (1880) examines the realities of sexual exploitation at that time; and Germinal (1885) transports us to the dark underbelly of life in the coalmines. Each novel stands as testimony to the reality of an age and for this reason, the Rougon-Macquart cycle is held up as a monument of the French Naturalist Movement in theatre and literature.

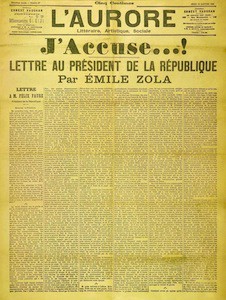

As a Naturalist writer, Zola believed that ugly social problems could not be solved as long as they remained hidden from view, unexamined and undiscussed. This was no less true for Zola the person as well. In January 1898 he took on the entire military leadership under President Félix Faure, accusing them of obstruction of justice and anti-Semitism.

Zola’s role in the Dreyfus Affair

Here’s what lead Zola to advance such a charge:

In 1894, a young artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent named Alfred Dreyfus was brought up on charges of allegedly passing French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris. He was tried, convicted and sentenced to life in solitary confinement on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. Two years later, new evidence revealed that Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, a known scoundrel with no real affection for France – or any nation for that matter—was the truly guilty party. But high-ranking French military officials, not wanting to cast doubt on their judgment in general, suppressed the facts. What’s more, they fabricated documents to further substantiate Dreyfus’ conviction, using him as a convenient scapegoat to cover up their own lack of judicial due diligence.

In a famous example of rare journalistic bravery, Zola risked his own reputation and career—he was by now France’s wealthiest and most respected writer—to expose the Third Republic for falsely convicting Dreyfus of treason based on nothing more than naked bias. His vehement open letter, J’Accuse, in which Zola taunts the government to arrest him as well, forced the re-opening of the Dreyfus Affair. The succeeding political scandal divided French society well into the 1900s, but truth finally won out.

Just as Zola had attempted in fiction, so had he achieved in life itself.

Though Esterhazy received little more than a slap on the wrist, after which he fled to Brussels to live out his life on a French military pension, Dreyfus was ultimately exonerated in 1906, all accusations against him having been proved baseless. He was reinstated in the French Army and served with distinction during World War I as Lieutenant-Colonel Dreyfus.

The cost of speaking out for justice

Zola, unfortunately, would not live to see the result of his valor. Following the Affair, he was both lionized and vilified; a hero to some, he was a traitor to others. In standing up for Alfred Dreyfus and for social justice, Zola had also proven the power of the intellectual to shape public opinion. He was convicted of criminal libel in February 1898, just one month after the publication of J’Accuse. To avoid prison, he fled, arriving in London with only the clothes on his back. He hated it there and returned to Paris as soon as he could, in June 1899, just in time to see Faure’s government fall. In September 1902 he died at home from carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a blocked chimney. Though his enemies were suspected of foul play, this being one of several attempts on his life since the Dreyfus Affair, nothing was ever proven. He was only 62 years old.

Émile Zola, father of French Naturalism, defender of truth, crusader for justice, was originally buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre. A tombstone still marks the one-time grave. But on 4 June 1908, Zola, too, would be exonerated in the eyes of the French people. His remains were exhumed and removed to the Panthéon where he now shares a crypt with Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas.

All venerated 19th century authors, ardent Republicans who spoke out for social justice and reform, there can be no doubt that Monsieur Zola would agree that in death he shares fine company indeed.

Sarah Towle is Founder & Creative Director of Time Traveler Tours, interactive mobile itineraries for teens, ‘tweens and the young at heart that put history in the palm of your hand. Learn more about her groundbreaking StoryApp tours . The first tour in the Time Traveler Tours Paris series, Beware Madame la Guillotine! is expected to launch June 2011. Sarah also maintains a weekly blog about French history and culture and what it means to build an App. Jettez à coup d’œil.

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Zola

Germinal Cover

J’Accuse

Esterhazy

Link to explanation of Republican Calendar

A Paris hotel we think you’ll like . . .

Hotel Montalembert is a modern, chic boutique hotel with just over 50 suites in the chic Saint-Germain-des-Prés district. The superb Haussmannian entry and classic, elegant Parisian architecture is enhanced with modern comfort and style. All suites have flat-screen TVs, iPod and Wi-Fi access. The library and its superb fireplace offer a cosy and elegant setting for a business meeting, teatime or an evening drink. Lovely terrace beside restaurant on site. More about this hotel here at Booking.com.

Hotel Montalembert is a modern, chic boutique hotel with just over 50 suites in the chic Saint-Germain-des-Prés district. The superb Haussmannian entry and classic, elegant Parisian architecture is enhanced with modern comfort and style. All suites have flat-screen TVs, iPod and Wi-Fi access. The library and its superb fireplace offer a cosy and elegant setting for a business meeting, teatime or an evening drink. Lovely terrace beside restaurant on site. More about this hotel here at Booking.com.

Booking.com is part of Priceline.com, the world’s leading online hotel reservations agency. Booking.com offers competitive rates for any type of property, ranging from small independent hotels to five-star luxury. If you find the same room for less, Booking.com guarantees to match the rate.

More in Bonjour Paris, Dreyfus Affair, Emile Zola, French history, history, J'Accuse, Jewish history, Jewish Paris, Montmartre Cemetary, Paris, Paris history, Paris writers, scandals, writers in Paris, Zola