The Jewishness of Marcel Proust at the mahJ

“If I didn’t respond yesterday to what you asked about Jews, it was because of this simple reason: I am Catholic like my father and my brother, while on the other hand, my mother is Jewish. You understand that’s reason enough to abstain from this kind of discussion.” (A letter to Count Robert de Montesquiou, May 1896)

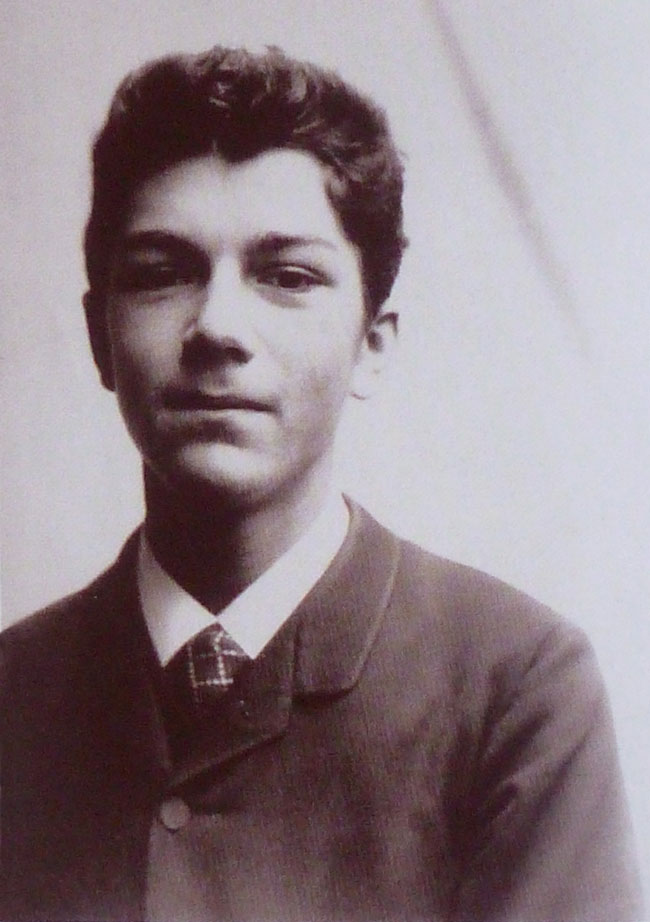

On November 18, 2022, we mark the 100th anniversary of Marcel Proust’s death in Paris, in that famous corked-lined room that muffled the noises outside his self-imposed confinement. He had celebrated his 51st birthday that previous July 10th. Born into a cushy haut-bourgeois family in 1871, six months after the tumultuous Franco-Prussian War ended on January 28th, he began life in Auteuil in the 16th arrondissement, ensconced in privileges that wealth and rank could enjoy. The current exhibition Proust from his Mother’s Side, at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaïsme (Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, or mahJ), tries to make the case that Proust’s mother Jeanne Clémence Weil, who belonged to a prominent, assimilated Jewish French family (what the French called israélite, as opposed to the juif/ French-born Jews vs. the newly-arrived Jewish immigrants), exerted a major influence on his development, hence imposing a “Jewishness” (judéité) that few scholars or fans have bothered to explore.

Anaïs Beauvais, Madame Jeanne Clémence Proust, 1878 Oil on canvas, 78 x 65.5 cm, Illiers-Combray, Maison de tante Léonie – Musée Proust

This premise is quite courageous in view of the literature on Proust’s Jewish side, which often argues against making too much of his access to Jewish culture and traditions. Robert Alter wrote in his New Republic review of Evelyn Bloch-Dano’s Madame Proust: A Biography, translated by celebrated Yale professor Alice Kaplan, (University of Chicago Press, 2008): “Madame Proust’s social legacy to her son was not to pass on to him her ancestral heritage, but, through the sheer vibrant presence of her family, to impart to him a doubleness of perception that helped to make him a shrewd and searching chronicler of French society.”

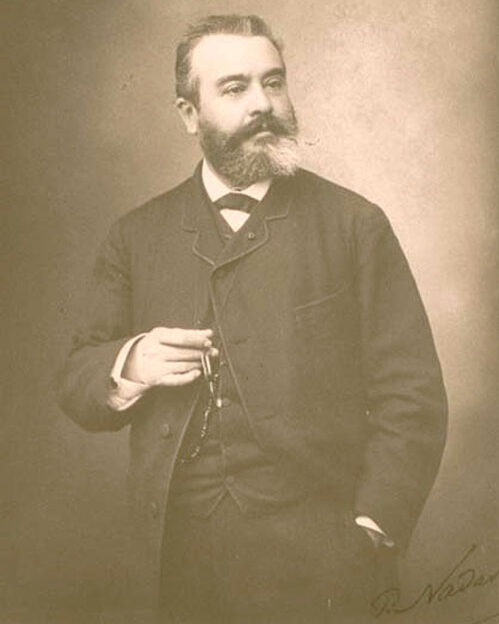

Paul Nadar, Dr. Adrien Proust, c. 1890 Charenton, Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine

I entered the current Proust exhibition at mahJ (closing August 28th) with Alter’s opinion in mind and left half-converted. Not that I felt Proust’s self-declared Catholic identity should be set aside, but rather that the thesis for this show is overdetermined in order to “jew-dify” Proust beyond his own comfort level, his preferences for identification.

In the mahJ director’s introduction, Paul Salmona identified Proust as “un modern marrane.” The French call this “marranism” – a term borrowed from the Spanish word “Marrano” – the converted Jews, the “hidden” Jews, the ones who chose to stay when the Spanish Inquisition tried to expel the entire Jewish population. The French word refers to the mixed Jews or the assimilated Jews whose outward appearance and manners conform to Christian norms, but once in private, alone with family or co-religious friends, their authentic Jewishness breaks through. Marrano is an ugly slang expression; it means “pig.” I wonder if Salmona knows this.

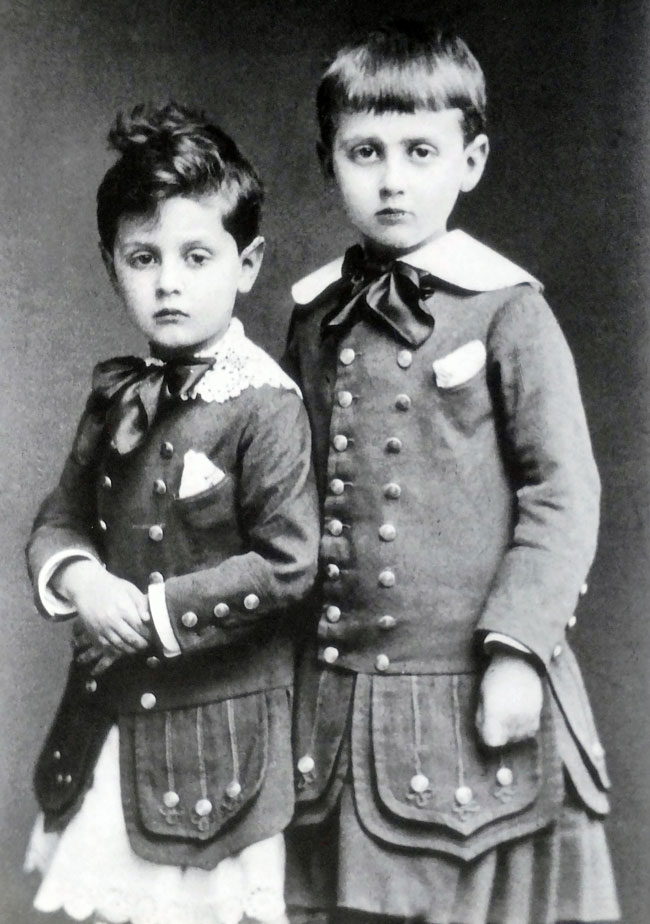

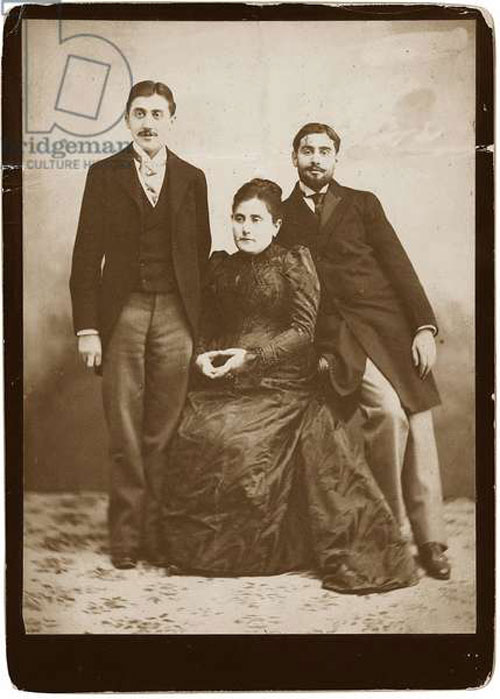

Modeste Chambay, Robert and Marcel Proust, 1877 Illiers-Cambray, Maison de tant Léonie – musée Marcel Proust

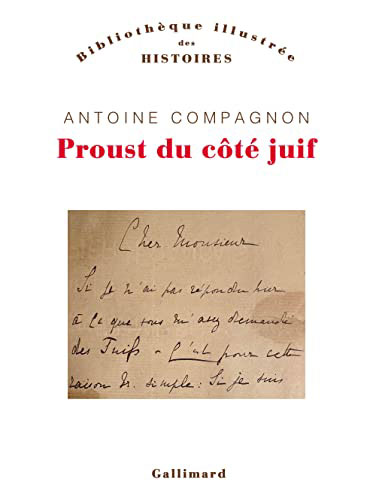

Be that as it may, the director of the mahJ invited the Academician Antoine Compagnon, Blanche W. Knopf Professor of French and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, to lead an exhibition about Proust’s Jewishness to the extent it has not been considered heretofore. Compagnon has a theory. During le confinement, he shared his theory on Zoom with various audiences, speaking in French and English, in France and abroad, in advance of his book’s publication, which occurred this past March 2022. I caught the lecture hosted by the Maison Française at Columbia University. In this recording Compagnon spoke in English with fellow Proust scholar Elisabeth Ladenson, who also contributed an essay to the mahJ catalogue for this Proust show.

Cover of Antoine Compagnons book on Proust

Compagnon’s lecture and his book The Jewish Side of Proust rely on two main supports: Proust’s letter of condolence to his dear friend, French historian Daniel Halévy, whose father Ludovic had passed away on May 7, 1908, and the Zionist newspapers’ obituaries for Proust published in 1922 and 1923. Ludovic Halévy was a celebrated librettist of numerous well-known operas, such as Bizet’s Carmen, which he wrote with Henri Meilhac in 1875, and the son of a Jewish convert to Christianity, Léon Halévy. We don’t know the context for Proust’s sentence, but Compagnon feels sure it expresses Proust’s genuine connection to his Jewish roots: “There is no longer anybody, not even myself, since I cannot leave my bed, who will go along the rue du Repos to visit the little Jewish cemetery, where my grandfather, following a custom he never understood, went for several years to lay a small stone on his parents’ grave.” It should be noted that laying a small stone on a tombstone, in lieu of flowers, is a traditional Jewish custom, rather than Jewish law. One does not have to be Jewish to leave a stone to mark one’s visit to the gravesite, nor is it prohibited for a Jew to leave a stone on a Christian gravesite. (In case you are interested, Ludovic Halévy’s grave is located in Montmartre Cemetery.)

Photo of Daniel Halévy, c. 1885, photographer unknown; source: Wikipedia

One has to wonder why this recollection of his grandfather going to the cemetery came to mind as he was trying to comfort Daniel Halévy. Did Proust and his fellow Christian-Jewish friend swap reminiscences of their respective memories of Jewish grandparents? Or was this a bit of nostalgia for the customs that connect the dear departed with the living? Compagnon found the quote in an obituary for Proust published in May 1923 in The Jewish Chronicle, a British newspaper. The writer was the French poet, critic, and Zionist André Spire. Compagnon thinks this Zionist context is significant. He looked for other obituaries in Zionist newspapers and discovered another in Menorah, written by Georges Cattaui, published on December 22, 1922, one month after Proust’s death. To the Zionists’ way of thinking, Proust’s A la Recherche is a very Jewish book. For them, Proust’s unsympathetic portraits of his Jewish characters serve as cautionary tales against assimilation.

John Ruskin, La Bible d’Amiens (The Bible of Amiens, 1884), translation, annotations, and preface by Marcel Proust [and Jeanne Proust] Paris: Sociéte du Mercure de France, 1904.

Praise of Proust in these Zionist periodicals reveals more about the journalists than Proust himself. For learned Jews know Halakhah, Jewish Law. According to Jewish Law, children of a Jewish mother must be recognized as 100% Jewish, regardless of whether they observe Jewish rites and rituals, or remain “secular.” Even baptized Jews may return to their Jewish identity after cleansing themselves in the mikveh, a Jewish ritual bathhouse, or a pond (wherever there is flowing water). Therefore, according to Jewish Law, Proust was 100% Jewish.

However, for the Jew who willingly and deliberately separates himself from the Jewish community, the situation does have serious consequences. For example, we read in the Haggadah, the book that organizes the Passover Seder, about the Four Sons — the Wise One, the Wicked One, the Simple One, and the One Who Knows Not What to Ask. The Wicked Son asks “What do you mean by this service?” By choosing “you” and not “we,” he withdraws from the Jewish community himself, and by doing so, the Haggadah tells us “he would not have been thought worthy to be redeemed.”

Weil Family Tree. First Gallery of Proust du Côté de la Mère. Photo credit: Beth Gersh-Nesic

Was Proust a “Wicked Son”? In his Search for Lost Time, Proust’s unattractive characterization of Jews seems to come from his alter-ego, “Marcel,” the Narrator, who speaks in the first person singular. “Marcel” is not Jewish. Thus, Proust manipulates his characters and his plot from a viewpoint that may or may not belong to his true nature or scruples. Among his Jewish characters, we meet the debonair assimilated Jew Charles Swann, whose refined manners turn to pushiness after he marries Odette, a “former courtesan.” Odette is eager to climb the social ladder as Madame Swann. Albert Bloch, an aspiring Jewish playwright, receives the Narrator’s critique of his “race” which fails to perceive social subtleties. Bloch eventually changes his recognizable Jewish name to a generic French moniker: Jacques de Roziers (an obvious reference to the well-known street in the Jewish section of the Marais, the rue des Rosiers). Swann’s daughter Gilberte changes her last name to her stepfather’s, de Forcheville, when her mother, Swann’s widow Odette, remarries, and then Gilberte changes her last name again when she marries a member of the aristocratic Guermantes family, Robert de Saint-Loup, thus erasing her nominal Jewish heritage entirely. And Rachel, a frisky actress, briefly Saint-Loup’s mistress, exhibits a louche behavior ascribed to her “natural” [Jewish] genes. If these portraits of fictional Jews do not set your teeth on edge, Proust’s alter-ego, “Marcel,” the Narrator, offers up even more antisemitic commentary in the form of the drawing room gossip which ferrets out the Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards during the Dreyfus Affair era (1894-1906). In short, it is hard to ignore Proust’s numerous Jewish references and blatant condescension.

Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ, Adolphe Crémieux, 1878 and Otto Wegener, Marcel Proust, c. July 27, 1896, photo of the first entrance to the exhibition, Source: Beth Gersh-Nesic

We begin our tour of the Proust exhibition in a large gallery surrounded by the Weil Family Tree and portraits of Proust’s parents, Jeanne Clémence Weil (1849-1905), Adrien Achille Proust (1834-1903), and other relatives. Jeanne’s father Nathé Weil (1814-96) was a stockbroker; her grandfather Baruch Weil (1780-1828), originally from Alsace, owned a porcelain factory in Fontainebleau. Her mother Adèle Berncastell (1824-1890) came from a prominent Parisian Jewish family too, dealers in porcelain, hardware, and such. Adèle Berncastell Weil’s Aunt Amélie married the French Minister of Justice and president of the Alliance Israélite Universelle Adolphe Crémieux, and through those connections, Adèle participated in salons frequented by Princess Matilde and the Comtesse de Haussonville (whose portrait by J.A.D. Ingres hangs in New York’s Frick Collection). Both Proust’s mother and father, a noted epidemiologist, provided a rich cultural and intellectual milieu for their sons Marcel and Robert Émile (1872-1934). Robert became an eminent urologist, gynecologist, and surgeon. He received the Chevalier de Legion of Honor in 1915 and was promoted to Officer in 1925.

Henri Gervex, Une Soirée au Pré Catelan, 1909 Oil on canvas, 217 x 318 cm, musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

Once informed about the Proust pedigree, we head toward the stars of the show: elegant artwork showcasing the opulent world of the “beau monde” during the Belle Epoque (1880-1914). Here high-society artists Jacques-Émile Blanche, Paul César Helleu, Léon Bonnat, and Henri Gervex, along with their Post-Impressionist contemporaries Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, and Fauve Raoul Dufy, capture the people and playgrounds Proust knew at gatherings in restaurants, in their homes, at the seaside, or off in “the country.”

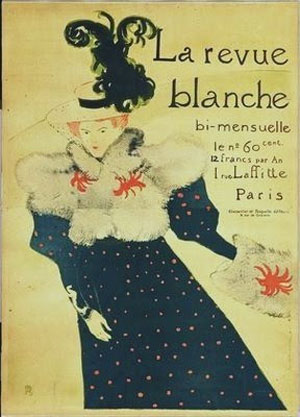

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Misia Natanson Sert on the cover of The Revue Blanche, 1895 Color Lithography, 130 x 94 cm. Paris, Private Collection

The modernist artists were cultivated by the Jewish brothers Natanson (Thadée, Alexandre, and Louis-Alfred), Proust’s friends from the Lycée Condourcet, who founded La Revue Blanche in 1889. Proust contributed to the magazine, which gave him access to not only numerous artists, but also musicians, composers, and writers of the time, including Claude Debussy (music), Stéphane Mallarmé (poetry), and Octave Mirbeau (novels and plays). Leaving this blissful mélange of academic gentility and adventurous artistic execution, we move onto the Queen Esther Galleries.

Jean-Jacques/James Tissot, The Circle of the Rue Royale, 1868 Oil on canvas, 175 x 281 cm, Paris, musée d’Orsay (The Jewish Charles Haas stands on the extreme right, at a noticeable distance from the other members of this elite coterie.)

Why is Queen Esther in A la Recherche du Temps Perdu and what role do artworks about Queen Esther play in this show about Proust’s Jewishness through his mother. First, a word about Esther, the heroine of a “book” in the Hebrew Bible. Esther (aka Hadassah) was the cousin of Mordechai. They were two Jews who allegedly lived several centuries ago in Persia. She hid her Jewish identity in order to compete for the hand of the Persian king Ahasuerus. The king fell in love with her, they married, and then antisemitism reared its ugly head. The prime minister Haman felt insulted by the Jew Mordechai who wouldn’t bow down to him as Haman passed by in the streets of Shushan. Incensed, Haman asked the king to pass a law that would kill all the Jews on the 14th day of Adar. Mordechai sent word to Esther through a messenger to ask for help. He asked her to appeal to the king to save her people. Reticent at first, she invited the king to a meal that would predispose him to her wishes. She invited Haman too. Pleased and sated, she simply requested the men come to her apartments again. Then, after a second festive meal, she told Ahasuerus that Haman planned to kill her and all “her people.” The king condemned Haman and Esther saved the Jewish people in all of Persia from complete annihilation.

Frans Francken the Younger, Esther Before Ahasuerus, c. 1622 Oil on wood, 72 x 103 cm, Collection Marie-Claude Mauriac

The beloved Purim fairytale receives an entire gallery devoted to the images of Queen Esther in paintings, prints, a photograph of Sarah Bernhardt in this dramatic role, and Purim paraphernalia. Proust invokes the Esther story several times throughout A la Recherche, in art as well as on stage. More surprising and exciting, the mahJ displays an Esther painting by the 17th-century Flemish artist Frans Francken the Younger painting (c. 1622) which Jeanne Proust inherited from her family and bequeathed to her sons. Also, Proust’s close friend and lover Reynaldo Hahn composed “divine choirs” based on Racine’s play Esther (1689) in 1904, which Proust’s mother “preferred to all others,” Nathalie Mauriac Dyer quotes in the catalogue essay on this subject. This frequency of Queen Esther references reminds me of Proust’s letter to Lucien Daudet in 1906, which is quoted at the beginning of Isabelle Cahn’s catalogue essay: “it would be so nice, before I die, to do something that would have pleased Maman.” These references to Queen Esther would have indeed pleased Maman, the queen of her own mixed-marriage household. Jeanne Proust died on September 26, 1905.

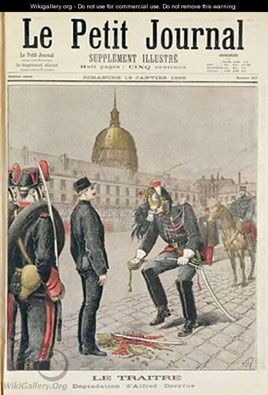

Henri Meyer, “The Traitor: The Degradation of Alfred Dreyfus,” Le Petit Journal, January 13, 1895, Literary Supplement Lithography, 45 x 31.4 cm, Paris, Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaïsme

Moving on to a small gallery in an alcove, we see a room devoted to the Dreyfus Affair. Here, this scandalous antisemitic incident is illustrated through a series of drawings by Hermann-Paul (1897-98) and Maurice Feuillet (1899). The drawings include Captain Alfred Dreyfus’ arrest for treason, his conviction, his exile on Devil’s Island, and portraits of the deceitful perpetrators who framed this innocent Jewish officer.

Léon Bonnat, Portrait of Charles Ephrussi, 1906 Oil on panel, 46 x 38 cm, Collection of Élisabeth de Rothschild

From this gallery we turn the corner and find a magnificent portrait of Charles Ephrussi (1849-1905) by Léon Bonnat, next to Manet’s delicate stalk of asparagus, a gift to Ephrussi when he overpaid for Manet’s painting of a bundle of asparagus (1880), both missing from the Ephrussi show at the Jewish Museum exhibition in Manhattan. Charles Ephrussi and Charles Haas are considered the models for Proust’s main Jewish protagonist Charles Swann.

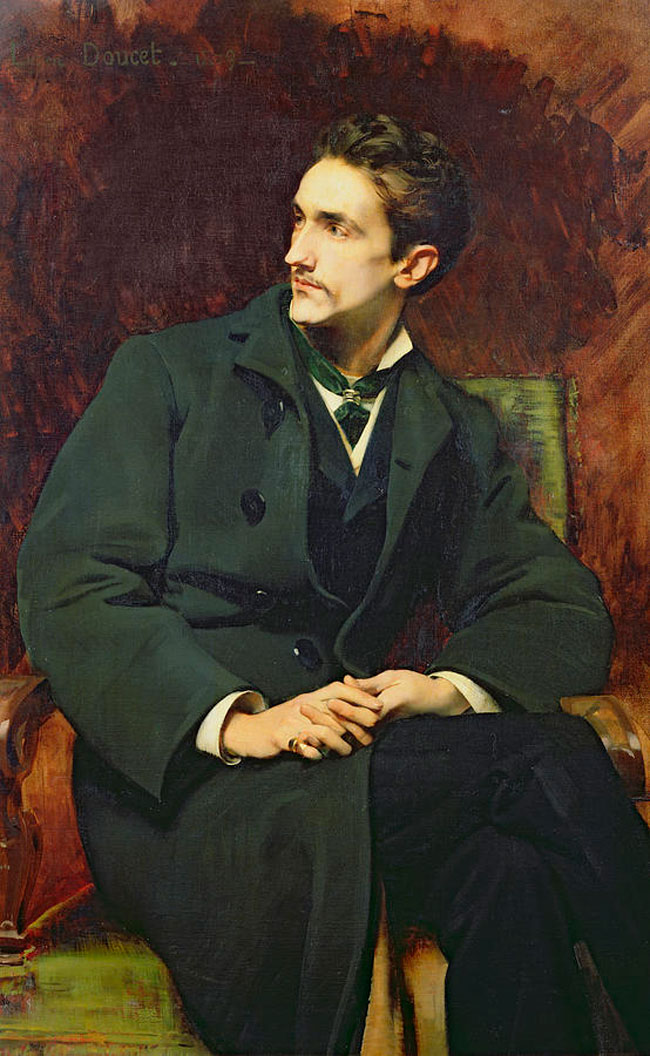

Henri-Lucien Doucet, Portrait of Robert de Montesquiou-Ferenzac, 1879 Oil on canvas, 129.5 x 86.5 cm. Établissement public du château, du musée et du domaine national de Versailles

And then, we turn to a section on Proust in the “inverted” world. This segue may seem abrupt, but according to Elisabeth Ladenson in her catalogue essay “Jewishness and Inversion,” the Dreyfus Affair “is foundational in [Proust’s] analogy between Jews and homosexuals.” Homosexuality and Jewish markers pop up often as leitmotifs throughout the seven volumes of A la Recherche. In Proust’s fourth book, Sodom and Gomorrah (aka Cities of the Plains), the author links the two. He compares Jews to “inverts,” his name for homosexuals, who played a significant role in his life as his lovers and confidents. It should be noted that his alter-ego in A la Recherche, “Marcel,” is not Jewish and not gay.

Oscar Wilde, a modern reprint of a photograph by Napoléon Sarony, 1882, Roger-Viollet

As the Narrator or as Proust himself (one never knows which deserves the credit or blame), the omnipresent “voice” of this book decides that both Jews and homosexuals shun “one another, seeking out those who are directly their opposite, who do not desire their company, pardoning their rebuff, moved to ecstasy by their condescension; but also brought into the company of their own kind by the ostracism that strikes them, the opprobrium under which they have fallen…” In other words, Proust decided that the similarity between Jews and closet homosexuals is their desire for acceptance among those who hate them the most. The exhibition illustrates Proust’s view of this interconnection by displaying several portraits of well-known gay friends, such as Count Robert de Montesquiou (1855-1921) and Oscar Wilde (1854-1900).

Jacques-Émile Blanche, Ida Rubenstein as Zobéide in Schéhérazade, 1911 Oil on canvas, 148 x 181 cm. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra, départment de la musique.

The last galleries display the best part of the show: colorful paintings, actual costumes, original theater posters, set and costume designs, and much more. Here, Jacques-Émile Blanche’s large, spectacular Ida Rubenstein as Shéhérazade (1911) and Tamara Karsavina as “The Fire Bird “(1910) rule over this capacious space. After an enormous amount of visual and archival material at our disposal, it feels relaxing to just take pleasure in these exuberant homages to legendary prima ballerinas. Anyone who thinks they know Jacques-Émile Blanche’s style well (evident in his portrait of Proust at the beginning of this article) will be stunned to discover this other side of his oeuvre. Here, astonishingly, Blanche executes his brushstrokes loosely and constructs playfully to give the illusion of movement. Truly a welcome surprise among so many well-known artistic examples. Congruent with this experimental expression is Auguste Rodin’s sculpture of Nijinski, (1912), which tries to arrest the dancer’s movements in space.

To complete our tour, we can also indulge in a few short clips from film adaptations of Proust’s Swann’s Way, with Jeremy Irons (1984) and Time Regained (1999).

Marcel Proust, First corrected proofs of Du côté de chez Swann 1913 40 x 60 cm Switzerland, Cologny, fondation Martin Bodmer

By the time I reached the end of this extremely beautiful exhibition which featured Marcel Proust, his mom Jeanne, and a whole host of glittering Jewish celebrities from the late 19th-early 20th centuries, it seemed unnecessary to worry about whether Antoine Compagnon had cracked the Jewish code in Proust’s personal life and/or writing. Proust’s Jewishness was not the revelation that began to haunt me. Instead, I wondered whether Marcel Proust would appreciate this exhibition and its attendant criterion. The answer may come from Proust himself, in the form of sentence from a letter to his mother (1899), which the curator Isabelle Cahn quotes in her catalogue essay. A certain M. Galard spotted Proust at the Splendide Hôtel in Evian-les-Bains, and Marcel reported the encounter this way to his mom: “’You’re the M. Weil’s nephew,’ [he asked] with an air of unmasking me that I really did not like at all.” What caused the discomfort? Pointing out his connection to the Weil family, with “an air of unmasking” his Jewish lineage? For Proust, it was a breach of privacy, redolent of an unwelcome slight. Cahn confirms: “Proust never laid claim, in public, to being Jewish. He was not ashamed of his roots but feared antisemitic attacks which he had witnessed and which his family told him about.”

Perhaps a better approach to an exhibition at the mahJ to honor the 100th anniversary of Proust’s death would have been a general survey of Jewish high-society and its contribution to the arts during the Belle-Epoque, something like “Proust and his Crowd,” 1871-1922, without the insistence on determining how Jewish or not Jewish Proust should be considered today. Remember Proust’s complaint to his Maman: “‘Vous êtes le neveu de M. Weil,’ d’un air de me démasquer qui m’a fort déplu.” (“‘You’re M. Weil’s nephew,’ with an air of unmasking me that I really did not like at all.”) Perhaps, this overly determined attempt to reveal Proust’s inherent Jewishness goes over the line as well.

NOTES

Here is a review of Antoine Compagnon’s book Proust du Côté de Juif.

Marcel Proust du Côté de la Mère, at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaïsme, March April 14-August 28, 2022. For more information and reservations, visit the museum’s website. (Address: Hôtel de Saint-Aignan, 71 Rue du Temple, 3rd arrondissement; Tel: +33 (0)1 53 01 86 53; closed Mondays.)

All translations are my own except Proust’s letter to Daniel Halévy, translated on screen during Professor Compagnon’s lecture at the Maison Française de Columbia University, November 18, 2020.

And the quote from Sodom and Gomorrah, in Remembrance of Things Past, translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff, volume II (New York: Random House, 1932), p.14

Jeanne Weil Proust with her sons Marcel and Robert, c. 1896? Anonymous photographer. Paris, bibliothèque de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art. En dépôt à Paris, Bibliothèque National de France.

Lead photo credit : Jacques-Emile Blanche, Marcel Proust, 1892 Oil on canvas, 73.5 x 60.5 cm, Musée d’Orsay

More in history in Paris, history museum, Marcel Proust, Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaïsme

REPLY

REPLY