Americans in Paris: Sylvia Beach, Founder of the Influential Bookshop, Shakespeare & Company

In Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, where many of his erstwhile Parisian compatriots were subjected to often exorable criticisms, Sylvia Beach remained unscathed. Hemingway wrote, “No-one that I ever knew was nicer to me.”

George Whitman, a friend of Sylvia Beach, who opened his own bookshop in 1951, La Mistral, in Rue de la Bucherie, renamed it Shakespeare and Company in her honor (1964). When Whitman’s only child was born in 1981, he named her Sylvia Beach Whitman. Sylvia Beach Whitman still runs Shakespeare and Company, overlooking Notre Dame cathedral, six years after her father passed away.

Such was the esteem and affection in which Beach was held, both during her life and after, that her many kindnesses and sheer hard work helping writers (and musicians) promote their work to a wider public, were rewarded by the fierce loyalty of not only her many friends but also an impressive literary elite of the time.

The original Shakespeare and Company was opened in rue Dupuytren in 1921 by this quiet, unassuming American. Small and slender, Sylvia had– according to Hemingway— “a lively, sharply sculptured face, brown eyes that were as alive as a small animal’s and as gay as a young girl’s, and wavy brown hair that was brushed back from her fine forehead and cut thick below her ears.” Hemingway also approved of her pretty legs, writing that she was, “kind and interested, and loved to make jokes and gossip.”

Sylvia first saw Paris in 1902 when her father, the Reverend Sylvester Beach, came to assist the Reverend Thurber with the Presbyterian ministry for Americans in Paris. He was accompanied by his wife Eleanor and their three daughters, Holly, Eleanor (who called herself Cyprian) and Nancy, who preferred to be called Sylvia. The Reverend Sylvester Beach’s piety did not rub off on his wife Eleanor who encouraged her daughters to travel and imbued in them her own love of Europe, and for Sylvia in particular, her love of Paris. After three years, the Beach family returned to Princeton. In 1907, Sylvia returned to Paris and then on to Italy where she studied for a year. Her mother Eleanor, unhappy in her marriage, and always eager to be back in Europe, made several trips back to France, without her husband but with her daughters. Cyprien was by then a successful actress in France and Sylvia, staying with her in her apt in Port Royal, decided to help the war effort by joining the Volontaires Agricoles in the Touraine, picking grapes and grafting trees. The hard work, side by side with the strong, no nonsense women of the Touraine, suited Sylvia’s character (she could never shake off her Victorian upbringing, although the piety and religious beliefs of her father left her unconvinced and conflicted). It also suited her strong desire to be useful to the very best of her ability.

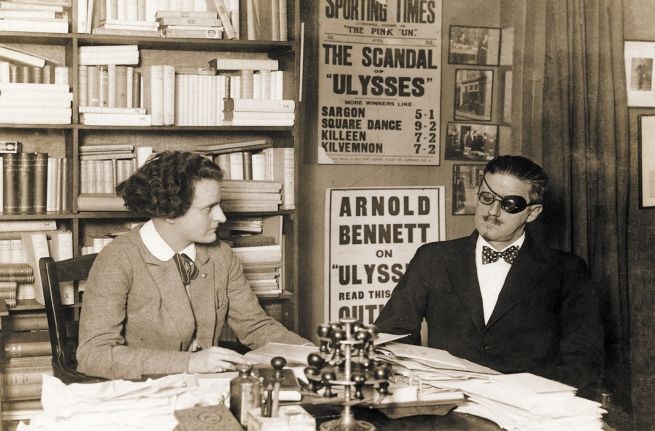

Beach and Joyce at Shakespeare & Company

As yet, Sylvia had no vocation, though she was interested in journalism and poetry, multilingual, and a more than proficient writer. Openings for translators or journalists in war-time France were few and far between.

A chance meeting in the rue de l’Odéon would not only change Sylvia Beach’s life but also influence the lives of scores of English-speaking writers in Paris.

On the Left Bank, No 7 rue de l’Odéon was the home of Adrienne Monnier’s bookshop, ‘La Maison des Amis des Livres’ and one windy afternoon in 1918, Sylvia impulsively entered the welcoming warmth of Adrienne’s bookshop. There was an instant rapport between the two women that was to last a lifetime which inspired Sylvia, finally, to find the vocation she had been longing for and a soulmate for a partner.

Before making her decision to open a bookshop, Sylvia and Holly traveled to Serbia to work as secretaries and translators for the Red Cross in a country still devastated in the aftermath of the war. The experience made a feminist of Beach as women had no say in Red Cross decisions and in general were held in low esteem. It was during this period that the idea of opening a bookshop crystallized. New York was too expensive, London was discounted on the advice of Harold Monro who owned the Poetry Bookshop, and Paris, combined with the lure of Adrienne Monnier, became the inevitable choice.

It was Adrienne who had found the shop which had formerly been a laundry, around the corner from rue de l’Odéon, in the small rue Dupuytren.

With the help of $3,000 from her mother, Beach paid six month’s rent and transformed the bleak premises into a warm and welcoming environment replete with antique furniture from flea markets, sack cloth covered walls and a profusion of paintings and drawings. A wood burning stove heated the shop and the small kitchenette beyond. There was no bathroom.

Beach had always envisaged that the bookshop would also be a lending library and finally on November 17th, 1919, Shakespeare and Company opened for business.

The bookshop was an immediate success with Americans in Paris but what Beach had not accounted for was the support of Adrienne’s illustrious French friends and clientele. André Gide, Léon-Paul Fargue, Valery Larbaud and Jules Romains all flocked to Shakespeare and Company, enchanted by the atmosphere of the bookshop and the range of English and American literature on offer.

It wasn’t long before James Joyce entered Sylvia Beach’s bookshop and almost single handedly consumed the next ten years of her life. Joyce, who had found it impossible to get Ulysses published, found his saviour in Sylvia Beach. She not only took on the herculean task of publishing his vast work but also became his editor, banker, secretary and unpaid factotum, taking on his family’s problems of finding accommodation and doctors, liaising with prospective international publishers and editors and organising subscription lists to finance the publication of his book. Shakespeare and Company became his post office and bank and sometime place of refuge. James Joyce doubtless helped make Sylvia Beach perhaps the most famous woman in Paris but it came at a cost, both for the financial stability of Shakespeare and Company and Sylvia’s personal life. Adrienne Monnier, incensed at Joyce’s treatment of Sylvia-he would ask her to get him theatre tickets or pick up his laundry-sent Joyce a strongly worded letter. Monnier’s and Joyce’s friendship cooled as a consequence, but this was nothing compared to the hurt and sense of betrayal when Joyce sold out the publishing rights of Ulysses to Random House for a $45,000 advance. Beach did not receive a penny after ten years of unremitting hard work– even organizing the smuggling of copies of Ulysses into the US and the UK.

It would be impossible to overestimate the passion and commitment Beach had for Joyce’s work. She never wavered from her belief that Joyce was a genius and that everything humanly possible must be done to publish his books– and one book most of all, Ulysses. (Beach’s counterpoint in England, Harriet Shaw Weaver, who financed Joyce’s often lavish lifestyle with unstinting support, although often shocked and disapproving of his extravagance and drinking, became great friends with Sylvia Beach over the years. Without these two women, the outcome of Ulysses and indeed James Joyce may well have been very different. Neither sought public acknowledgment and neither was justly rewarded for their years of dedication to Joyce and his family.)

By May 1921, Shakespeare and Company had outgrown the premises in rue Dupuytren. Its popularity with the huge influx of Americans and British to Paris in the 1920s necessitated the move to bigger, more prominent, premises at 12, rue de l’Odéon, almost opposite Adrienne’s bookshop.

Beach’s library membership was impressive, the young Hemingway and Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas were some of the first to join. Ezra Pound, T.S Eliot, Sherwood Anderson and F. Scott Fitzgerald were just a few of her illustrious clientele. The bookshop flourished through the 1920s, although there were times when the publishing costs of Ulysses almost bankrupted her. By the 1930s, with the mass exodus of Americans from Paris, sales dropped significantly and Beach was forced to consider the unthinkable: closing Shakespeare and Company. André Gide stepped in to save the day and persuaded literary friends to subscribe as Friends of Shakespeare and Company– paying an annual fee of 200 francs.

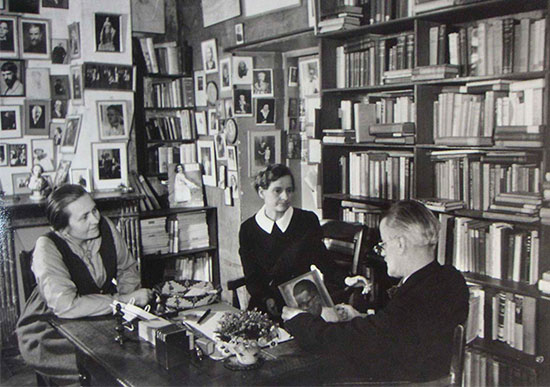

Beach with Monnier and Joyce at Shakespeare & Company

It wasn’t until 1941– when a German officer, after Beach refused to sell him her personal copy of Finnegan’s Wake, threatened to return the following day and confiscate her books– that Beach cleared the shop and hid all the books upstairs on the empty fourth floor. The Shakespeare and Company sign was painted over and after 22 years, the bookshop was no more.

Sylvia was taken to an internment camp but after six months was released and returned to Adrienne Monnier on the rue de l’Odéon to sit out the war.

She never re-opened the bookshop although she retained the premises above which contained her fourth floor apartment. Released from the pressures of Shakespeare and Company, Beach did not slow down but took up charitable work, attended lectures and returned to writing and translating, always with the support and love of Monnier.

Monnier had been in ill health since 1950, and in 1954 was diagnosed with Meniere’s disease. She suffered nine months of relentless, delusional noises. This, combined with her debilitating rheumatism, proved to be too much to bear and Adrienne took an overdose of sleeping pills from which she didn’t recover.

She died on June 19th, 1955. She had been Sylvia Beach’s, partner, lover, and soulmate for 38 years.

In the seven years that followed Monnier’s death, Sylvia Beach’s inestimable contribution to literature and James Joyce’s career was finally acknowledged. She traveled widely and was feted and sought after; she even became financially secure, after a lifetime devoid of monetary riches.

After vacationing in Les Déserts, where she and Adrienne had spent dozens of summers in their spartan retreat, Sylvia returned to her apartment in the rue de l’Odéon. There she was found dead from an apparent heart attack on October 6th, 1962.

She was cremated after a simple service in Père-Lachaise cemetery. Her ashes were buried the following year in Princeton.

The plaque above the door of 12, Rue de L’odeon, simply states:

En 1922

Dans cette Maison

Mlle Sylvia Beach publia

“ULYSSES”

De James Joyce.

Read more articles in our Americans in Paris series.

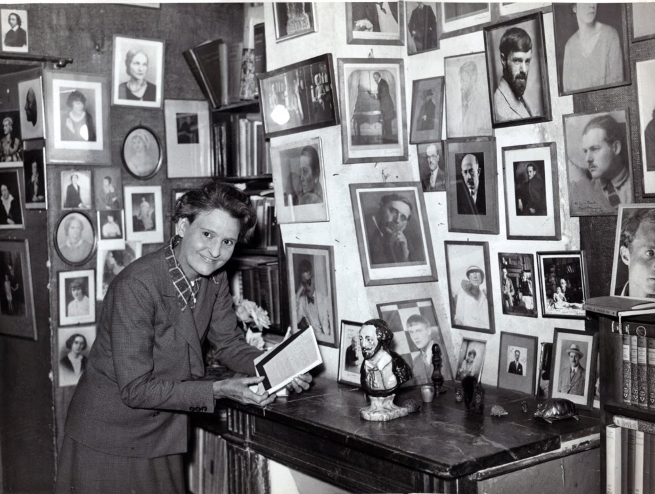

Lead photo credit : Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare & Company

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY