Sainte Geneviève: The Woman Who Saved Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

At one end of the Pont de la Tournelle stands a statue of a woman. She is looking upriver, hands on the shoulders of a child. Despite standing high above the Seine, the sculpture’s pale grey stone makes her hard to distinguish from a distance, but this is a statue of Paris’s second patron saint: Sainte Geneviève (the other one, of course, is the headless Saint Denis). She gazes eastwards, in commemoration of Geneviève’s most famous act – facing off the invasion of Attila the Hun. But there was much more to her than defeating the notorious Mongolian barbarian. She was also a mystic and shrewd political operator, who enabled, at least indirectly, the spread of Christianity across the future country of France.

Pont de la Tournelle. Photo credit: Patrick GIRAUD/Wikimedia commons

Geneviève is often depicted with a lamb by her side, which has led to stories that she was a simple shepherd’s daughter. In fact, she came from an aristocratic Gallo-Romano family with political connections. She was born in or around 423CE at Nanterre, just a few kilometers to the northwest of Paris. Far from being an uneducated country girl, it seems likely that she was brought up to take a keen interest in politics and would have been very aware of the disintegration of the Roman Empire around her. On the other hand, she was also well-known for her religiosity: when she was just seven years old she was presented to Bishop Germain de l’Auxerre, who was traveling through Nanterre and who remarked on her extreme piety.

It’s not surprising, then, that when she was around 15, Geneviève moved to Paris and “took the veil,” deciding to dedicate her life to the service of God. She was ascetic in the extreme: her diet was composed of barley bread and beans which she ate just twice a week (extreme diets are nothing new!) and she undertook prayer “marathons” of nonstop praying for days on end. As you might expect from such a regime, Geneviève was prone to religious visions; these days skeptics would probably call them hallucinations brought on from semi-starvation. Either way, Geneviève continued to gain a reputation in Paris, not always favorable. People were frightened by this extremely thin, ultra-pious woman who was not afraid to declaim her visions to anyone who would listen.

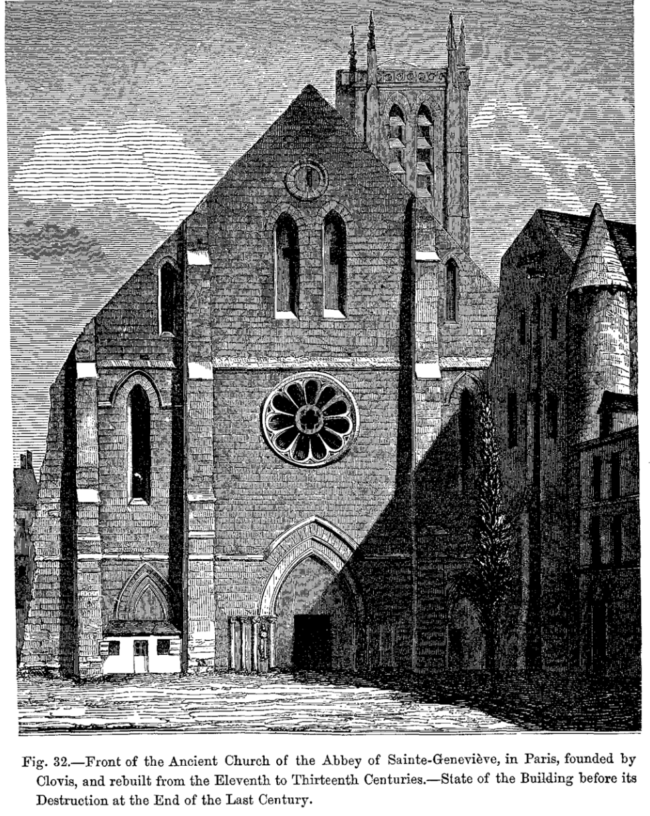

The former Abbey of St Genevieve. F. Kellerhoven – Project Gutenberg. Public domain.

On the other hand, her family connections provided an introduction to Paris’s ruling authorities and soon she was advising them. By this time – around 450 – the city still boasted substantial Roman remains but as each decade passed these were disappearing. As civilized Roman rule receded further into the past, Parisians increasingly felt vulnerable towards the “barbarian” tribes which were spreading across Europe.

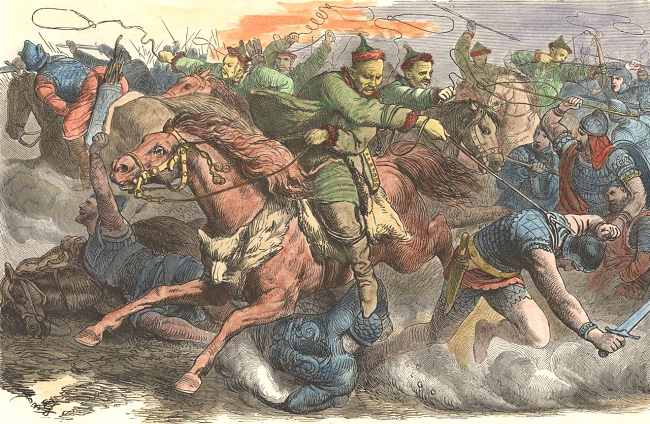

No tribe was more feared than the Huns, led by their notorious leader Attila. Originating in Asia, they steadily marched westward, cutting a huge swath across Europe. The many legends around Attila the Hun have made him a byword for cruelty and ferocity, but the myths do seem to have a basis in historical fact. His troops marched relentlessly into western Europe, looting and pillaging at will, burning towns and villages, raping women indiscriminately. And as happens with any invasion, Attila pushed a huge wave of refugees ahead of him.

King Attila as the first Hungarian king in the Chronicon Pictum. Public domain

Inevitably, many of these refugees ended up in Paris, bringing with them their experiences of villages looted and burned and their womenfolk assaulted and taken into captivity. Not surprisingly, when Parisians heard these horrific stories they were all for abandoning the city and fleeing. They were not exactly keen to see the same fate befall them and their families.

Step forward Geneviève. She intensified her starvation diet and embarked on ever-more rigorous prayer sessions. She announced to the populace that she had had a visitation from God, who had told her that if the people of Paris were dutiful and prayed to Him, He would be merciful and spare Paris from the heathen.

You can imagine how that went down with the average Parisian. They may have been, in modern terms, superstitious and credulous but they weren’t completely gullible and many scoffed at Geneviève and her visions. To them, praying was not going to be much of a deterrent against Attila. However, she was not put off by nay-sayers and she persevered. Gradually, she gathered around her a small group of believers.

Huns in battle with the Alans. An 1870s engraving after a drawing by Johann Nepomuk Geiger (1805–1880). Wikimedia Commons

Then, one day, the inevitable happened and Attila arrived at the gates of Paris. Well, not quite; he actually camped on the banks of the River Marne. But as Parisians would discover a millennium and a half later, that was close enough for soldiers to march into the city within a day. According to legend, one morning Geneviève led her little band of acolytes out of Paris to a hill just beyond its fortifications where they prayed from sunrise to sunset. When night fell they returned to the city. Next morning, they awoke to find a miracle had happened – Attila had gone. That, at least, is recorded history. He decamped and set off southwards towards Lyon. The legend goes that he decided the women of Paris weren’t worth raping, but maybe he simply thought Paris wasn’t worth besieging. However, the important thing was that he no longer posed a threat.

Of course, all those people who had called Geneviève a madwoman now hailed her as the savior of Paris and in honor of her success at repelling the barbarians she was made a patron saint of the city. Perhaps, though, her longest-lasting achievement was to demonstrate the power of Christianity at a time when many people were skeptical of Christian beliefs.

Saint Genevieve praying to stop the rain during the harvest (Notre-Dame de Paris). Photo: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT/Wikimedia Commons

Geneviève continued to powerfully influence local politics. Attila was not the only barbarian to threaten Paris: just a few years later the north of the country was overrun by the Franks who established a kingdom covering much of northwestern Europe. The Franks were almost as barbaric as the Huns and terrorized their conquests. Their king was Clovis, an unrepentant pagan. It is a testament to Geneviève’s diplomatic skills and charisma that she managed to inveigle her way into the heart of the Frankish court. She befriended Clovis’s wife Clothilde, who was conveniently Christian and, through Geneviève’s influence, persuaded Clovis to be baptized. Clovis’s conversion to Christianity was probably fairly cosmetic; the records show little evidence that he reined in his bloodthirsty and violent instincts afterwards. However, once the king was a Christian, his lords and nobles felt obliged to follow suit, and in turn they would “persuade” the peasants on their lands also to convert. The country later known as France was already a patchwork of Christian and ancient pagan beliefs but it seems likely that, indirectly at least, Geneviève was responsible for helping Christianity become the dominant religion. She further persuaded Clovis to make Paris his capital – a status that would remain to the present day – and to establish a center of learning that eventually would morph into the University of Paris.

‘Bataille de Tolbiac’ (1836) by Ary Scheffer. Wikimedia Commons

She died in 512CE, and even if her birthdate is a little inexact, it is clear that she was well into her eighties when she died – a phenomenally old age for the period (maybe there is something to be said for a barley and beans diet!). She was buried in a church on the hill now named after her, the Montagne Sainte Geneviève. In later centuries the church was replaced and became that of Saint Etienne du Mont. In the Middle Ages a large abbey dedicated to Sainte Geneviève spread across the entire area now covered by the Panthéon (originally the site of the abbey church dedicated to her) and the Lycée Henri IV, and her remains in Saint Etienne du Mont became a place of pilgrimage. Her simple tomb was embellished into a full shrine and she became a patron saint of the sick, who would come to pray to be cured.

Shrine of Saint Geneviève in the church of Saint Etienne du Mont. Photo: Jebulon/Wikimedia Commons

This continued right up to the French Revolution, when the vehemently anti-clerical revolutionaries completely destroyed the interior of Saint Etienne du Mont. They pulled apart Geneviève’s shrine, a superstitious relic, and burnt her remains, throwing the ashes into the Seine. However, the parish priest did manage to salvage a few of the stone slabs from her sarcophagus, and a fragment of bone that he claimed was her little finger. To be honest, it looks too big to be a finger bone, but it could be a fragment of Geneviève’s skeleton. After the Revolution the church was restored, including Geneviève’s shrine. Today you can walk to the back of the church and still see it – and the bone fragment in a display case.

Geneviève lives on in the name of the hill, the place in front of Saint Etienne du Mont, and the beautiful library that runs alongside the Panthéon. Far from being a recluse, she was an engaged and politically savvy woman at the heart of political affairs, who was skilled at influencing the men who surrounded her. Not bad for a visionary mystic!

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève – Université Sorbonne Nouvelle. Photo: Priscille Leroy/Wikimedia Commons

Lead photo credit : St. Genevieve as patroness of Paris, Musée Carnavalet. Unknown painter. Public domain.

More in history, People, Saint Genevive

REPLY