How Clovis and Charlemagne Shaped Today’s France

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Imagine coming face to face with two of France’s ancient rulers, Clovis and Charlemagne. You can if you go to the Musée Grevin, the wax museum in the 9th arrondissement. They are both there, large as life, right at the beginning of the History of France section. To look them in the eye, as I did recently, is to be transported back in time, before France was even France, and to wonder exactly who they were and whether they have left a legacy for the 21st century.

First, comes Clovis (466-511) whose blue-grey eyes stare reflectively into the middle distance and whose long blond hair and beard give away his Frankish (Germanic) roots. He became king of the Salian Franks, ruling over land which is today in Holland and Belgium, on the death of his father when he was only 15. He was such a fierce and ambitious warrior that by the end of his 30-year reign he had unified the various Frankish tribes, won decisive victories over the Romans and conquered much of Gaul. He ruled over more of what is now France than anyone had before him.

Clovis tomb at the Cathedral of Saint-Denis near Paris. Credit: Arnaud 25/ Wikimedia Commons

He was certainly ferocious, as the story of the “Vase of Soissons” shows. After defeating the Roman Syagrius at Soissons, in what is now northern France, Clovis allowed his men to plunder riches from the local church, but when the bishop pleaded to keep one particularly beautiful silver chalice, he relented. The soldier holding it was so furious he smashed the vase to the ground, rather than handing it back. A year later, Clovis met the same soldier on parade, remembered the incident, took an axe to his head and killed him. The troops watching this presumably quickly grasped the message that Clovis was to be obeyed without question.

St Remy, Bishop of Reims, begging Clovis for the restitution of the Sacred Vase taken by the Franks in the Pillage of Soissons. Credit: Maksim/ Wikimedia Commons

Clovis was highly effective. The historian John Julius Norwich writes that “he was a monster, often cold-blooded in battle,” and it is said that he was willing to assassinate even his own allies in his bid for power. But his rise was also thanks to other factors, such as marrying some of his children to leading members of rival tribes, thus drawing them into his orbit. As his position as the single ruler of the Franks became clear he was astute enough to declare the role hereditary, thus founding the Merovingian Dynasty which ruled for the next two centuries.

Clovis 1, King of the Franks. Credit: British Library / Flickr

A key factor which has influenced France right up until the present day is Clovis’ conversion to Christianity. His wife Clotilde was Catholic and keen that Clovis should adopt her faith. He resisted until one day before a battle he made a pact with God that if victorious, he would become a Christian. And so he came to be baptized on Christmas Day at Reims Cathedral in the year 508, along with 3000 of his troops. Cynics might say that Clovis allied himself with powerful church authorities to further his own ambitions and perhaps that was partly true. But he did preach his faith publicly and he built churches in Paris, notably La Basilique des Saints Apôtres Pierre et Paul on the site where the Panthéon now stands. It was there that he was buried, the first Christian king to be laid to rest in Paris.

Baptême de Clovis. Credit: Gallica Digital Library/ Wikimedia Commons

There are other reasons to remember him. Towards the end of his reign, Clovis passed the Salic Law, which replaced Roman Law and which is still cited as an important step in the development of modern France. He also oversaw the introduction of Latin as the language of administration and this, mixed with the Frankish language, gradually evolved to become modern French. So, both the laws and the language of 21st-century France have their early roots in Clovis and his reign. His name lives on, too, for Clovis is the root of “Louis,” later used for no fewer than 18 kings of France. No wonder Clovis is still revered today. In the 1990s Pope John Paul II celebrated mass in Reims Cathedral to mark the 1500th anniversary of his baptism.

The Baptism of Clovis. Credit: Samuel H. Kress Collection/ Wikimedia Commons

Next to Clovis in the Musée Grevin stands Charlemagne (742 – 814), his thoughtful face and greying hair set under the crown which signifies his role as the Frankish king, crowned in 768, who first drew squabbling parts of France back together and then so increased the lands over which he ruled, that the pope eventually crowned him emperor.

Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne, by Friedrich Kaulbach, 1861. Credit: Raboe001 / Wikimedia Commons

Ironically, this son of Pépin le Bref (Pépin the Short) grew exceptionally tall and had the fighting and tactical skills to be an excellent warrior. He dominated the Saxons, conquered Bavaria, became King of the Lombards; in short by the year 800 he ruled over a million square kilometers of territory. He was then crowned by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day in St Peter’s in Rome, becoming the first Holy Roman Emperor. He exercised a strong control over his empire, and so was hugely influential in the development of France and of much of the rest of Western Europe.

Europe at the death of the Charlemagne 814. Credit: Hel-hama / Wikimedia Commons

Charlemagne had a strong Christian faith and theologians like the English scholar Alcuin of York hoped that under him a common Christian faith would unite Europe, just as Roman citizenship had united it in earlier centuries. Some of his personal qualities sit awkwardly in this context. He is said to have rejected his first two wives after a few years of marriage and to have been so enraged at the refusal of some “pagans” to convert that he once had 4000 of them executed. But many historians praise him as a strong Christian ruler and admire the way he modernized and civilized the lands over which he ruled.

Charles Ier le Grand ou Charlemagne. Credit: Bibliothèque Nationale de France / Wikimedia Commons

Charlemagne ruled under a “bannum,” which gave him the powers to decide everything himself, or to delegate if he wished. Given the size of his empire, he wisely appointed deputies to make sure his new laws were enforced and so his reforms spread across all the lands he ruled. He was able to order legal, military and church matters across his vast empire and he greatly influenced economic matters too, introducing a standard weights and measures and a new currency, the denier, which was to be the only valid coin in his realm. He also saw it as his Christian duty to protect the church and try to improve the lot of the poor.

Denier from the era of Charlemagne, Tours, 793–812. Credit: PHGCOM / Wikimedia Commons

Charlemagne presided over cultural and educational progress too. He made his capital at Aachen, known in French as Aix-la-Chapelle, where he built a splendid palace and invited many of the day’s brilliant scholars to visit. He encouraged education through the monasteries, founded schools and an academy for young knights, and promoted the use of classical Latin, learning it himself to set an example. It is said that Charlemagne himself came late to reading and writing, but he certainly saw the value of learning and the Carolingian Renaissance he inspired has been referred to as “the end of the Dark Ages.”

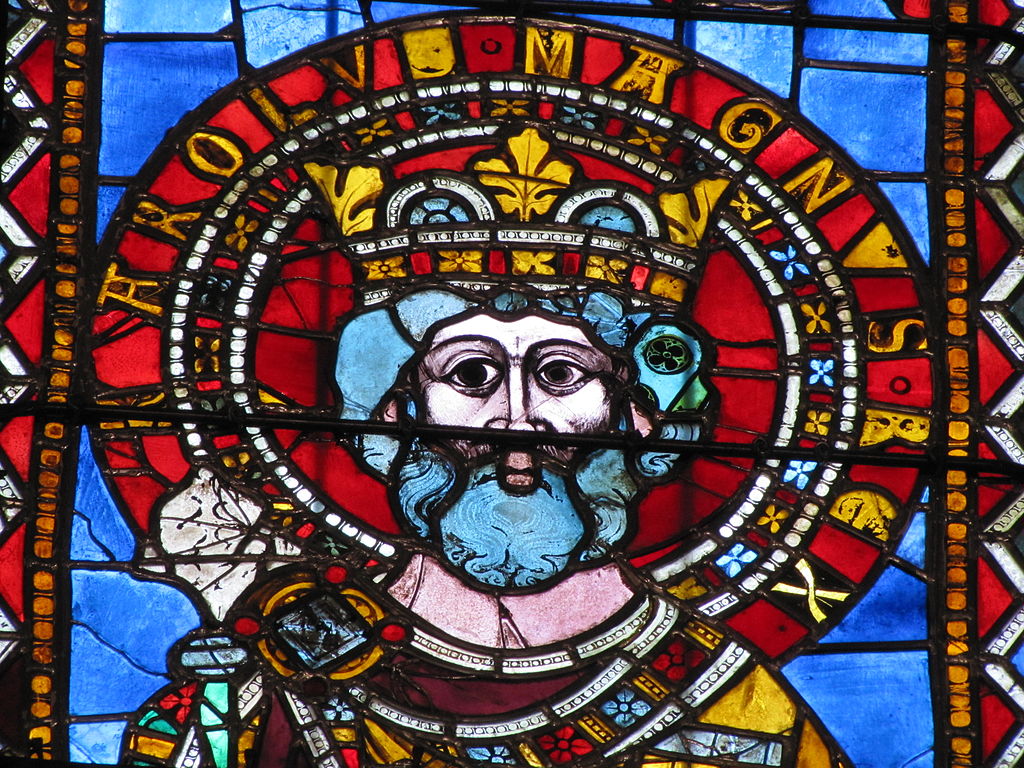

13th-century stained glass depiction of Charlemagne, Strasbourg Cathedral. Credit: Ralph Hammann/ Wikimedia Commons

So, these two rulers, born 300 years apart, both exercised enormous influence in their own time and both left modern France a legacy. Clovis, the first king of the Franks, defeated the last of the Romans, brought warring territories together into something beginning to resemble the land we call France today and did much to sow the seeds of its Christian heritage. Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, united much of western Europe for the first time since the Roman Empire, bringing reforms and progress and strengthening its religious roots. Both founded a dynasty – the Merovingians and the Carolingians – and both deserve to be remembered. How fitting then that it is Clovis, then Charlemagne who first greet visitors arriving in the history section of the Musée Grévin.

Lead photo credit : Clovis (left) and Charlemagne (right) wax works at the Musée Grevin. Photo credit: Marian Jones

More in Charlemagne, Clovis, history, kings, Musée Grévin

REPLY

REPLY