Robert de Montesquiou: The Ultimate Bon Vivant

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

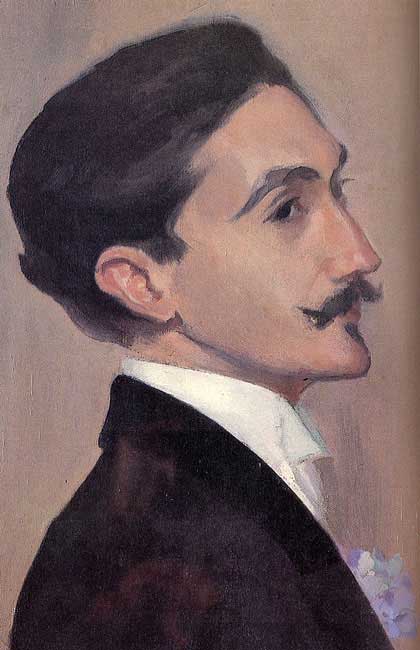

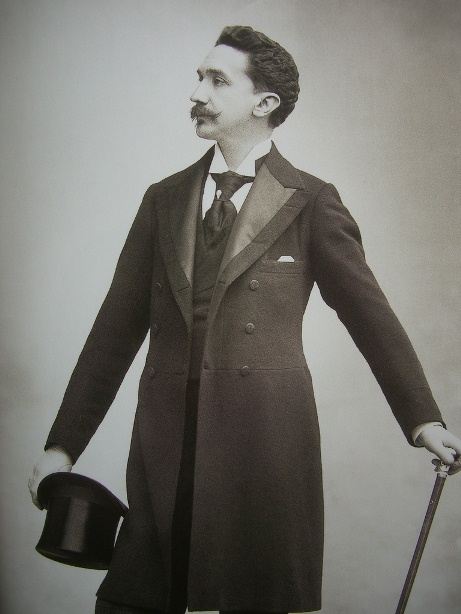

Painting by Jacques-Émile Blanche in 1887

The stylishly eccentric Comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fézensac was a royalist, social snob, drawing-room liberal, literary dilettante and Symbolist poet. With aplomb and cavalier elegance, he assumed a lofty position in both the fashionable and literary circles of the Parisian Belle-Epoque. Lean and graceful as an Abyssinian cat, he was incredibly handsome, with dark, wavy hair and a signature mustache that accentuated his striking Roman nose. Montesquiou and his family were direct descendants of the illustrious dukes of Gascony who could trace their lineage back to Merovingian kings, as well as the 16th century writer, Blaise de Monluc, and Charles de Batz de Castelmore d’Artagnan, the fourth Musketeer.

Marie Joseph Robert Anatole, Comte de Montesquiou-Fézensac was born in Paris on March 7th, 1855 to Thierry Montesquiou-Fézensac and Pauline Duroux. His paternal grandfather, Anatole, was an aide-de-camp to the Emperor Napoléon and a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. Thierry was a very successful stockbroker who left a substantial fortune to his four children, of whom Robert was the last. In fact, Robert luxuriated in such immense wealth that his lifestyle became legendary. As a young child, he was moved from chateau to chateau in the care of his grandmothers, who traveled with an assemblage of servants. As was the custom of the very wealthy, he was educated by the best tutors in a rarified milieu, but grew up lacking familial bonds.

In 1875, Montesquiou was invited to a ball given by a family friend, the Baroness de Pouilly, during which he was introduced to the poets and writers he earnestly admired: Barbey d’Aurevilly, Francois Coppée, José-Maria de Heredia, Catulle Mendès and Stephane Mallarmé. Within months he was invited into the salons where the intellectual youth of Paris gathered. They all noted his keen intellect, jocular nature, and the sincere respect he displayed for the literary profession. He became known as something of a consummate dandy. In the estimation of most people he had a silver-tongued devil’s wit and a proclivity towards homosexuality, which distinguished him early on as the French Oscar Wilde. He made amusing and often times lacerating remarks, and was by his own admission, “Addicted to the aristocratic pleasure of offending.” His meticulous attention to his personal appearance was captured In a charming book of memoirs by Elisabeth de Gramont, the Duchess de Clermont-Tonnerre:

“Leaning on the railing of my upper balcony one bright spring morning, gazing down onto the Avenue I was suddenly struck by the appearance of a tall, elegant personage in mouse-gray, waving a well-gloved hand in my direction as he emerged swiftly from the green shadow of the chestnut trees into the yellow sunlight of the sidewalk. He must have been in an unusually conservative frame of mind that day to have appeared in mouse-gray. He might, likely as not, have turned up in sky-blue, or in his famous almond-green outfit with a white velvet waistcoat. He selected his costume to tone with his moods and his moods were as varied as the iridescent silk which lined some of his jackets.”

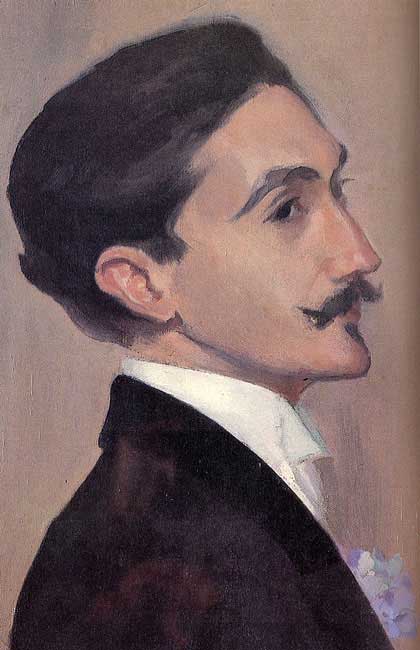

1903 drawing by Georges Goursat

Montesquiou also had a constantly shifting set of mannerisms. At the beginning of any conversation, he’d remove one glove and launch a series of gesticulations, raising his hands towards the sky, lowering them to touch the tip of one perfectly buffed shoe, or waving them as though conducting an orchestra. His conversations were usually long monologues filled with exotic anecdotes, mysterious allusions and obscure classical quotations, all told with a rich vocabulary. Quite often amused by himself, Montesquiou would burst into the shrill laughter of an hysterical woman, then just as suddenly clap his hand over his mouth to quiet himself. Most likely the reason for this abrupt gesture was that for all his disarming handsomeness, that his teeth were small and black.

When he was 28, he enjoyed his first marked success in the attic of his parent’s mansion on the Quai d’Orsay. He transformed his suite into a dandy’s heaven reached by climbing a dimly-lit spiral staircase. Visitors entered through a tapestry-carpeted tunnel. Each room was decorated to fit a mood: one painted in shades of red, another in a muted symphony of gray. The windows, with panes of pale blue crackle-glass or gilded bottle-punts, cast a soft light upon the elaborate interior decoration and were framed by curtains made out of old ecclesiastical robes, the gold threads of which sparkled against the red material. Tiger skins and blue fox furs covered the floors throughout, surrounding an enormous, 15th century money-changer’s table, deep-seated wing-armchairs and old church pews. The chimney-piece was covered by a sumptuous, Florentine silk fabric and flanked by two Byzantine monstrances of gilded copper. Antique musical instruments hung from the ceilings. Parisians marveled.

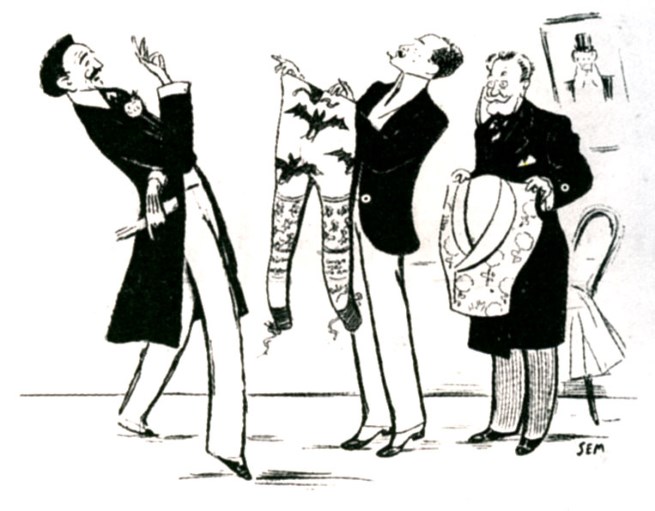

photo: public domain

As a young bon vivant, Montesquiou encapsulated the romantic, literary and aesthetic excesses of his predecessors – Lord Byron, Charles Baudelaire, and Beau Brummell – while adding his own unique style. Baudelaire had decorated his rooms at the Hotel Lauzun in an unconventional and capricious manner, while the English dandy, Beau Brummell, had been lionized in print by the author Barbey d’Aurevilly. As careful in his pursuit of art as Lord Byron was careless in his pursuit of life, Montesquiou’s oeuvre was refracted through many lenses ultimately becoming the model anti-hero of the decadent movement portrayed in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ book, À Rebours, Against the Grain. The highly controversial novel catalogued the eclectic tastes and inner life of Jean des Esseintes, an eccentric antihero who eschews 19th-century bourgeois society and retreats into an artistic world of his own creation. Not content to remain the living image of Huysmans’ creation, Montesquiou moved from his famous d’Orsay quarters to the Rue Franklin, leaving most of his furnishings behind, while taking his growing collections: a bird-cage owned by Michelet, a lock of Lord Byron’s hair, Beau Brummell’s cane, Baudelaire’s sketch of his mistress Jeanne Duval. His dearest friend and cousin, The Countess Greffulhe, had even allowed a plaster cast of her chin to be made.

Montesquiou’s next fascination was the Art Nouveau Movement with its oriental overtones. A Japanese gardener was hired to tend his small forest of dwarf pines trees, a rare collection of miniature oaks, and delicate maples. His bedroom was an Arabian Nights’ fantasy of heavy curtains, low sofas, satin cushions and hanging brass lamps fitted with colored glass. An immense beaten copper kettle supplied water for a Persian bath in the dressing room. Many pieces were commissioned from Émile Gallé, and René Lalique, the famous glass-makers of the period. In homage to her cousin and friend, the Countess de Greffulhe, even installed a red lacquer bridge and a pagoda at her mansion.

Art Nouveau, image: Alphonse Mucha – Art Renewal Center Museum

Another family friend, the Prince de Polignac, introduced Montesquiou to the newly-arrived American writer, Henry James, who in turn introduced Montesquiou to the artist, James Whistler, with whom he became a close friend and confidante. The fashionistas of the Faubourg St. Germain, and the wealthiest society wives, were also included in his inner circle: Baroness Adolphe de Rothschild, Countess Potocka, Marquise de Casa-Fuerte, Princess Bibesco, along with his cousin, the Countess de Greffulhe and Ida Rubinstein, a Russian dancer who performed with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, then quit to form her own company. Montesquiou also embraced the literary world of Stephane Mallarmé, Alphone and Léon Daudet, Paul Verlaine, Edmond de Goncourt, Paul Bourget, Judith Gautier, and Robert Haas. As an impresario of the arts he accumulated a remarkable bouquet of talent: Claude Debussy, Gabriel Fauré, Anatole France, Marcel Proust, Eleonora Duse, Sarah Bernhardt, John Singer Sargent, the young Jean Cocteau, among many others.

In spite of being a social butterfly, Montesquiou had time to write poetry, many essays, two novels, various biographies, and three volumes of memoir. His books, privately printed and sumptuously designed, didn’t bring him the respect nor the public attention that he craved. Ladies of fashion flocked to hear him read his poems, but he was dismissed by the critics as a dilettante, though a gifted amateur, with money and taste, to be sure, but very little talent. He brushed off the criticisms by saying, “It is better to be noticed than remain unknown.”

Always keen to be at the forefront of style, Montesquiou grew tired of the Art Nouveau movement and shifted his interests to Versailles, where a mansion on the Avenue de Paris was leased to suit his latest tastes. Enthralled by the majesty of the Sun King, he had himself photographed as Louis XIV. The summer garden parties in his new home showcased his genius for entertaining, turning every gathering into a living tableau. The choice of flowers and colors for each occasion, the arrangement of music, the menus, and the careful selection of guests, gave him immense delight. He adored creating two lists of people, “the inviteds,” and “the excluded”. The later were chosen solely to be mocked. Montesquiou was fond of saying, “I prefer the parties themselves to the people I invite to them.” It is a testament to his influence as a taste-maker that high society followed in his footsteps for 30 years.

Palais Rose today. photo: Moonik

In 1893, at a fancy dress ball held on the lawns of the Trianon, with his guests costumed as the Royal Court, the painter, Madeleine Lemaire, introduced Montesquiou to one of his shy admirers, Marcel Proust. Proust quickly ingratiated himself with Montesquiou, who soon became his patron. Proust was almost religious in his fawning, to the point of imitatiing his gestures, his pose, and even his high-pitched laugh. With a mixture of bewilderment and awe, Proust gradually became privy to the scandalous details, and secrets of high society. Unfortunately, Montesquiou underestimated and disregarded Proust’s perfect memory and ignored his insatiable desire for gossip. Unbeknownst to him at the time, he again became the model for the main character in a novel, the cruel, homosexual dandy, Baron de Charlus, in À la recherche du temps perdu, The Remembrance of Things Past. The adulteries, bankruptcies, and disgraces of the upper class with which Montesquiou had regaled Proust with over the twenty years of his patronage, were meant to be enjoyed, not recorded. After the first three volumes of Proust’s manuscripts were published, Montesquiou read them with bitter recognition. “I am in bed, ill from the publication of three volumes which have bowled me over..”, he confessed to a friend. “Will I now be reduced to calling myself Montesproust?”

An unexpected wild card entangled Montesquiou in one of the most profound tragedies of Belle Epoque Paris. During the annual Charity Bazaar of 1897, 126 people, mostly women, perished in a devastating fire. Sixteen-hundred of the crème de la crème of Parisian society were gathered in the temporary timber hall on Rue Jean-Goujon off the Place de Vosges, eager to support the bazaar’s charitable causes. At one end of the building, the older children in attendance were entertained by one of the first screenings of projected motion pictures. In the late afternoon at one of these screenings, the Moltoni projector lamp suddenly went out and the room was plunged into darkness. While the projectionist struggled to refill the lamp with ether, he asked his assistant for more light. The assistant made the tragic mistake of striking a match and the ensuing explosion caused a jet of fire to shoot across the booth. Within minutes, the wooden floor and the fabric adorning the ceiling were ablaze. Panic ensued as the terrified children, society ladies, their servants and the nuns who had come to bless the charitable event attempted to flee the burning building. Eyewitness accounts told of women turned into human torches when burning tar from the roof fell on their heads, and others were trampled to death by men hastening to escape.

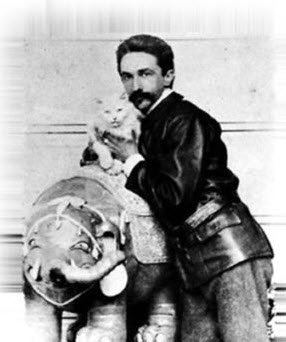

Montesquiou in 1895, photo: Paul Nadar, Publié dans Le Monde de Proust vu par Paul Nadar, édition du Patrimoine, 2000, ISBN:2-85822-307-6

A rumor circulated that Montesquiou was among the cowards who had fought his way to freedom using his cane. This was not true, for at the time of the conflagration he was nowhere near the rue Jean Goujon. Jean Lorrain, a columnist for the weekly paper, Le Courrier Francais, lost no time in publishing an account of the tragedy in his column. Montesquiou became the subject of gibes which gave rise to his one affaire d’honneur, not with Lorrain, but with the courteous and aristocratic writer Henri de Régnier. Régnier suggested at a soiree given by the Baronne Alphonse de Rothschild, that instead of a cane, Robert would do better to carry a muff. The remark was repeated to Montesquiou, and he lost no time in challenging Régnier to a duel. They met at an early hour in a deserted park at Neuilly. The park didn’t remain deserted for very long, however, for Montesquiou had sent out invitations to some hundred of his friends and acquaintances. They arrived at the park in varying states of sincere concern and wild amusement. Neither duelist had the slightest idea of how to handle a sword. After the signal to start Montesquiou leaped to and fro posturing like his ancestor, d’Artagnan. Eventually Régnier managed to cut Montesquiou’s thumb. An indulgent surgeon pronounced the minor incision a wound, the onlookers applauded, and the dual was considered done.

Throughout his life Montesquiou had many aristocratic women friends, but had no love affairs with them. Although in 1876 he reportedly slept once with the great actress Sarah Bernhardt. He much preferred the company of bright and attractive young men, and in 1885 he began a close, long-term relationship with Gabriel Yturri, a handsome South American immigrant, from Argentina who became his secretary, companion, and lover. After Yturri died of diabetes in 1908, Henri Pinard replaced him as secretary.

Even amateurs want to be recognized for their gifts, but by the time Montesquiou found himself in his mid-50s, he hadn’t received the recognition he thought he deserved and was thrown into a state of despair. His last years were devoted to impromptu séances and innocuous spiritualism. He took rest cures far from Paris, accompanied by Pinard, but his strength did not return. After packing up the remaining belongings from his last house, the magnificent Palais Rose, Montesquiou decided to spend the winter in Menton. He was 61 years old. He lived another three weeks. His body was brought back to Versailles where he was buried alongside Yturri at Cimetière des Gonards, Versailles, Île-de-France. Only 20 guests attended; none were relatives. Of all the poets, painters and personalities that he had touched with his patronage or cut with his tongue, only one came to mourn, Ida Rubinstein. One of his most famous quips followed him to his grave, “However amusing it may be to speak ill of one’s enemies, it is even more delectable to speak ill of one’s friends.” Pinard inherited what was left of his fortune.

The greatest shock of Montesquiou’s life was that he lived to see himself go out of fashion. In 1921, before his relatives could complain, the last chateau that remained in the family d’Artagnan was quietly sold to strangers. The rest of his belongings were bequeathed to his secretary: his collection of canes, engravings by Whistler, William Morris tapestries, Chinese vases, gilded writing desks, ebony chests, Gallé and Lalique glass, and 500 files that composed his correspondence and notes. Finally, there was the incredible collection of books, many rare volumes bound and decorated expressly for him, that made him one of the great bibliophiles of his day. Sold at auction, the three-volume catalog is now a collector’s dream.

Lead photo credit : Painting by Jacques-Émile Blanche in 1887

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY