Of Music and Muses: Hector Berlioz’s Obsessive Love

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It can often be said that love has no limits or boundaries, but obsession does. This is no more true than in the relationship between the French composer, Hector Berlioz, and the Shakespearean actress, Harriet Smithson.

In the years following the French Revolution (1789), a new movement called Romanticism flourished in France. Romantics were devoted to the pursuit of beauty, passion, love, spontaneity, feelings and emotions, rather than reason and logic. Among the most renowned proponents of French Romanticism were the painter Eugène Delacroix, the writer Victor Hugo, and the composer Hector Berlioz. Berlioz and Smithson’s love story remains the most representative of French Romanticism.

Louis-Hector Berlioz was born on December 11, 1803 in La Côte-Saint-André in Isère, near Grenoble. His father was a doctor and his mother a devout Catholic. As a young man he studied medicine in Paris, but his passion for music eclipsed his parent’s desire for him to follow in his father’s footsteps. Under the tutelage of the French composers Antoine Reicha and Jean-François Lesueur, he became a master of the symphony. Reicha had rubbed shoulders with Haydn and Beethoven in Vienna, and trained with Antonio Salieri, while Lesueur was Napoléon Bonaparte’s court composer and professor of composition at the Paris Conservatory.

Dosed with genius, Berlioz modernized the musical forms of his contemporaries Beethoven and Haydn, particularly with his extravagant and imaginative orchestral epic, Symphonie fantastique. The symphony tells the story of the composer’s self-destructive passion for a beautiful woman, by describing his desperate anguish and wild dreams with lyrical ecstasy and melancholic despair. That woman was Harriet Smithson.

Portrait of Harriet Smithson, Irish actress and wife of Hector Berlioz, 19th c. Public Domain

Berlioz was just 24 years old when a troupe of English actors came to Paris and gave a performance of William Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” at the Odéon Theatre, which he attended. Though the play was performed in English, and Berlioz didn’t understand a single word, the aspiring young composer became completely besotted both by the playwright’s skill and by the young Irish actress, Harriett Smithson, who portrayed Ophelia.

“Shakespeare, falling thus unexpectedly upon me, dismayed and astounded me. His lightning, in opening to me the firmament of art with a sublime thunderclap, illuminated the most distant depths. I recognized true grandeur, true beauty, dramatic truth…. My heart and whole being were possessed by a fierce, desperate passion in which love of the artist and the art were interfused, each intensifying the other.”

After the play he wandered the streets of Paris, lost in a torrent of emotions.

Harriet Smithson as Ophelia from title page of “La Mort d’Ophélie.” Public Domain

The following year Berlioz attended another of Shakespeare’s plays, “Romeo and Juliet”, in which Smithson played Juliet. His obsession with her continued to grow. He sent her flowers, numerous letters, and even appeared at her dressing-room door. He rented an apartment near hers so he could watch her coming and going, but she refused to meet him. Such was his obsession that his friends Franz Liszt, Felix Mendelssohn, and Frederic Chopin once “…had to go searching for him in the fields outside of Paris, afraid that he was going to kill himself.” (As quoted in a 2019 essay by Stephen M. Klugewicz in The Imaginative Conservative.)

Harriet Smithson (1800-1854) as Juliet in “Romeo and Juliet.” Public Domain

For the next five years the image of Smithson haunted his life. As he detailed in his memoirs,

“I come now to the supreme drama of my life. An English company had come over to Paris to give a season of Shakespeare at the Odeon. I was at the first night of ‘Hamlet.’ In the role of Ophelia I saw Harriet Smithson. The impression made on my heart and mind by her extraordinary talent, her dramatic genius, was equaled only by the havoc wrought in me by the poet she so nobly interpreted…”

Born in 1800 in Ennis, Ireland, Henrietta “Harriet” Constance Smithson was the daughter of a theater manager and local actress. At the age of 15 she debuted at the Crow Street Theatre in Dublin. By 1817 she played the Drury Theater in London, then crossed the Channel to Paris in 1827 where the company performed to packed houses. Her beauty and stage personality enchanted many artists, including the writers Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas, the romantic dilettante Emile Deschamps, and the young Berlioz. Smithson’s portrayals were remarkable for their time. Until then, tragedy was considered primarily a man’s domain. Her natural interpretations blurred the distinction between herself and the heroines she played, unwittingly seducing Berlioz who lusted, suffered, and ached, dreaming of no one but her.

The Irish actress Harriett Constance Smithson (1800-1854), by George Clint

Berlioz tried to overcome his passion by channeling his emotions into the ultimate romantic gesture by writing the Symphonie fantastique, which premiered at the Paris Conservatory on December 5, 1830. A young musician of “…morbid sensibility and fiery imagination”, frustrated with love, tries to kill himself with opium. But, instead of killing him, the drug gives him lavish hallucinations. The surprisingly delirious originality of the symphony from a 26-year-old composer made this work one of the most influential of the century.

Unfortunately, Smithson did not attend the premiere of the work she had unknowingly inspired. Shortly after the symphony’s debut, she left Paris for London. Berlioz wrote to a friend:

“She is in London…and yet I think I feel her around me… I listen to my heart beating and its pulsations shake me like the piston strokes of a steam engine. Every muscle in my body quivers with pain.”

George Clint: Harriet Smithson as Miss Dorillon, in “Wives as They Were, and Maids as They Are” by Elizabeth Inchbald. 1822. Public Domain

After winning the Prix de Rome music prize in 1830, Berlioz accepted a residency, hoping the distance between him and Smithson would dissipate his infatuation. Berlioz sincerely believed that he had exorcised his obsession by writing the symphony, and soon after, he began an affair with the young pianist Marie-Félicité-Denise Moke, which led to a brief, disastrous engagement. Marie had rejected him for the wealthy piano maker Joseph Étienne Pleyel, inciting him to elaborately plan to kill Marie, her mother, and Pleyel using poison, and two stolen double-barreled pistols. Ultimately, he did not go through with his plan.

Marie-Félicité-Denise Moke, 1840s. Public Domain

Returning to Paris in 1832, Berlioz rented an apartment on Rue Neuve-Saint-Marc only to discover that it had just been vacated by Smithson. Prompted by this uncanny coincidence, he arranged a second performance of the Symphonie fantastique, arranging for friends to invite Smithson. David Cairns describes the event in Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (Penguin, 2000):

“The room was buzzing. The program entitled ‘Épisode d’une vie d’artiste‘ and distributed to the public before the concert, described a story that hinted at Berlioz’s passion for Harriet. From her seat above the orchestra, Smithson could see the composer. The libretto and the effect of a large orchestra courting her touched the heart of the actress. Berlioz later wrote: ‘She felt the room rock; she no longer heard a sound, but she lay in a dream, and at last she returned home like a night owl, barely aware of what was happening.’ Within hours, Harriet sent her congratulations.”

Berlioz immediately sought and received permission to meet her and they became lovers. Despite her initial reluctance and the opposition of both families and friends, they were married at the British Embassy in Paris on October 3, 1833, with Liszt serving as best man. Louis-Clémont Thomas, the couple’s only child, was born on August 14, 1834.

In 1838, Berlioz began writing what many consider to be his greatest work: the seven-movement “dramatic symphony,” Roméo et Juliette. Shakespeare’s poignant tragedy had possessed him ever since he had experienced Smithson play the female title role a decade earlier: “To steep myself in the fiery sun and balmy nights of Italy,” Berlioz recalled, “…to witness the drama of that passion swift as thought, burning as lava, radiantly pure as an angel’s glance, imperious, irresistible, the raging vendettas, the desperate kisses, the frantic strife of love and death, was more than I could bear. By the third act, scarcely able to breathe — it was as though an iron hand had gripped me by the heart — I knew that I was lost.”

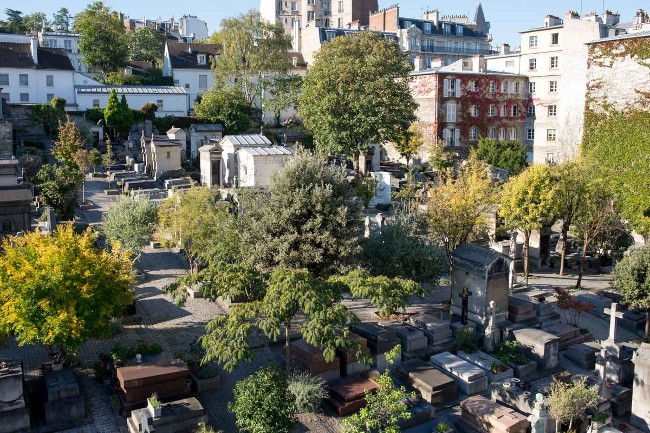

Cimetière de Saint-Vincent. Copyright: Jean-Pierre Viguié/ Ville de Paris

The first years of their marriage were relatively happy, but as Berlioz’s star rose, Smithson’s declined. She retired from the stage, took to drinking heavily, and became pathologically jealous and possessive. Eventually, Berlioz took a mistress, the opera singer Marie Recio, whom he would later marry.

Berlioz and Smithson were divorced, yet he cared for, and supported her, even as she became an invalid. She suffered from paralysis, which left her barely able to move or speak. She died on March 3, 1854, and was buried in the Saint-Vincent Cemetery in Montmartre. Stricken with grief, Berlioz left instructions that Smithson’s body be exhumed and buried next to his upon his death. Smithson’s remains were transferred to the Montmartre Cemetery where she joined Berlioz who died on March 8, 1869.

They rest together to this day.

Lead photo credit : Hector Berlioz (1803-1869). Public Domain

More in Harriet Smithson and Hector Berlioz, Hector Berlioz, Hector Berlioz History, Hector Berlioz Love Life