Edith Wharton: The Writer’s Life in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

An inveterate francophile who first traveled to France at the age of four, moved there permanently in 1910, and was laid to rest there in 1937, Edith Wharton enjoyed a life of privilege. Edith Newbold Jones was born in New York City on January 24, 1862; her parents, George and Lucretia Jones, shared deep, aristocratic roots dating back three centuries. The old saying, keeping up with the Joneses, was coined in reference to her family.

In 1866, just a year after the American Civil War, Edith’s parents took her and her two brothers, Frederic and Henry, to Europe, where they spent the next six years. Her father loved traveling and passed on his wanderlust to his daughter. He particularly loved the city of Paris. Images of the City of Light at the close of the 19th century made a deep impression upon Edith and remained with her for the rest of her life.

Portrait of Wharton as a girl by Edward Harrison May (1870)/ Public Domain

Though she received no formal education, Edith was instructed in philosophy, history, and poetry by English tutors, while the mannerisms and rituals that were appropriate to her social class were instilled in her by governesses. In addition to her native English, she was fluent in German, Italian, and French. Forbidden by her mother to read novels until she was married, by the age of 11 she had composed her first lines of poetry, and by 15, contrary to her mother’s wishes, she’d written her first novel.

undated photo of Edith Wharton/ Public Domain

In 1882, Edith’s short-lived engagement to Henry Leyden Stevens ended due to her “preponderance of intellectuality”, as noted in the local paper, Town Topics, publicly humiliating her and her family. Soon after, she met Walter Van Rensselaer Barry, an intellectually kindred spirit; however, his bewildering disappearance from her life ended their budding romance and opened the door to accepting a marriage proposal from Edward “Teddy” Robbins Wharton, a friend of her brothers and 12 years her senior. They married in 1885 when Edith was 23. Though not a love match, Teddy and Edith were cut from similar social cloth and shared a love of travel. Then, just as mysteriously as he left, Walter returned to Edith’s life, but it was too late. They would however, remain dear friends and close companions even after her marriage to Teddy. Themes of failed, unrequited love and lost chances took root in Edith’s psyche and would inform some of her most cherished, future novels.

Edith and Teddy lived a very comfortable life with homes in New York, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts, and spent at least four months of each year abroad. Edith would eventually cross the Atlantic 60 times. Over a period of time Edith grew dissatisfied with her limited role as wife and high-society matron. Conflicted by her husband’s inability to match her intellect and creative spirit, she grew restless and suffered from anxiety and depression. She was treated throughout the 1890s as was Teddy, who was, from all accounts, most likely manic-depressive. Consequently, their relationship became fraught with tension. In order to keep her mind occupied, Edith wrote The Decoration of Houses in 1897 and designed “The Mount” in 1902, their 113-acre estate in Lenox, Massachusetts, which survives today as an example of her considerable artistic prowess. She wrote several of her novels there, including The House of Mirth in 1905, the first of many chronicles of life in turn-of-the-century New York. At The Mount, she entertained the cream of American literary society, often including her close friend, novelist Henry James, who described the Wharton estate as “a delicate French chateau mirrored in a Massachusetts pond.”

53 rue de Varenne, where Edith Wharton lived by Monceau/Flickr

In 1907, on the heels of publishing The House of Mirth to rave reviews, Edith and Teddy traveled to France. Initially, they lived at the Hôtel de Crillon prior to subletting a formal mansion from George Vanderbilt, which is now an annex to the Hôtel Matignon, office of the French Prime Minister. She particularly adored the posh, private homes in the 7th arrondissement of the Faubourg St. Germain, where she frequented the well-attended salons of Rosa de Fitz James on the rue de Grenelle, now the Swiss Embassy. As Edith’s spirits soared in a Paris that welcomed worldly, intellectual women, Teddy’s declined. Refusing to learn more than the rudiments of the language, Teddy was cast in the shadows while his wife immersed herself in French literature. She even wrote the first draft of Ethan Frome in French.

It was at one of Rosa de Fitz James’s salons that Edith met Morton Fullerton, a handsome, seductively charming, bi-sexual American who was then a correspondent for the London Times, living in Paris. They soon engaged in a clandestine affair, meeting secretly and frequently at the Marly sculpture court in the Louvre, as well as the Jardin des Plantes and the Comédie Française. They often took long walks in the Tuilleries and Montmartre and occasionally traveled out of town together. Her affair with Fullerton ended when he abruptly disappeared from her life. She meticulously recorded all the details of their deeply intellectual and passionate relationship in her personal diaries, but these did not come to light until her papers, sequestered in Yale’s University’s Beinecke Library, were opened in 1968. None of her friends, nor her husband ever knew of her indiscretion. Teddy’s mental condition was ultimately deemed incurable, and they divorced in 1913 after 28 years of marriage. He returned to live in the States at his mother’s summer house in Lenox, where he died in 1928.

Between 1900 and 1938, Edith wrote over 40 books, both novels and novellas, and 85 short stories. Much of her time was spent either at The Mount in Lenox or at her apartment at 53 rue de Varennes. At both houses she held salons, hosting gatherings for the most gifted writers, statesmen, and intellectuals of her time. Theodore Roosevelt, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Bernard Berenson, Paul Bourget, André Gide,Jean Cocteau and her old friend, Henry James were all guests of hers at one time or another.

Photograph of writer Edith Wharton, taken by E. F. Cooper, at Newport, Rhode Island. Cabinet photograph. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. Public domain.

Edith’s life changed when World War I began. Though many fled Paris, she stayed at her home on the rue de Varennes and for four years was a fearless supporter of the French war effort. One of the first causes she undertook was the opening of sewing workrooms for unemployed women in August 1914. There they were fed and paid one franc a day. What began with 30 women soon doubled to 60 and kept growing. When the Germans invaded Belgium in the fall of 1914 and Paris was flooded with Belgian refugees, she helped set up the American Hostels for Refugees, which arranged to find them shelter, meals, clothes and work. In early 1915 she organized the Children of Flanders Rescue Committee, which gave shelter to nearly 900 Belgian refugees, who had fled when their homes were bombed by the Germans.

With the aid of her influential connections in the French government, Edith and her long-time friend Walter Berry (then president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Paris), were among the few foreigners in France allowed to travel to the front lines during World War I. She and Berry made five trips to the war zone between February and August 1915, viewing one decimated French village after another, which she described in dispatches first published in Scribner’s Magazine and later in her book, Fighting France: From Dunkerque to Belfort. It, too, soon became an American bestseller. On 18 April 1916, the President of France appointed her a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

View of the gardens at Wharton’s Le Pavilion Colombe in Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt, photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston/ Public domain

When the war ended in 1918, Edith decided to leave Paris. She settled in the Oise near the village of Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt, in an 18th-century manor house on seven acres of land, which she remodeled and subsequently named “Le Pavillon Colombe.” She lived there every summer and autumn for the rest of her life, spending her winters and springs on the French Riviera at her home in Sainte Claire du Vieux Chateau in Hyères. It was there in 1920 that she finished writing The Age of Innocence. With its publication the following year, she became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in literature. In the years following the war she returned to the United States only once, in 1923, to receive an honorary doctorate degree from Yale University in 1923.

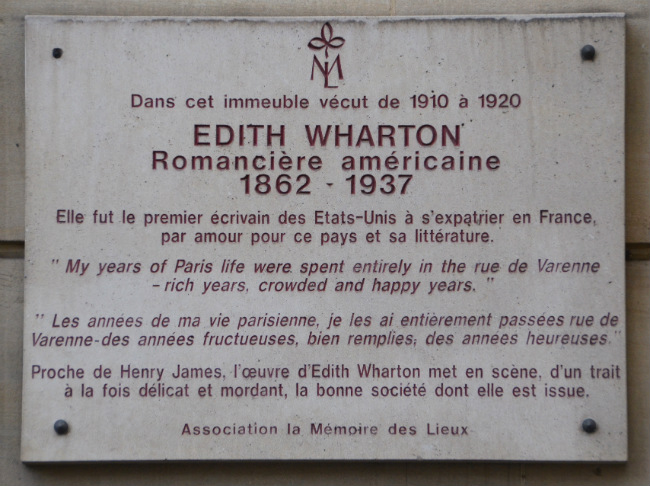

Edith Wharton died of a stroke on August 11,1937 at Pavillon Colombe. She was buried in the American section of the Cimetière des Gonards in Versailles next to her long-time friend, Walter Berry. Her lifelong love of France can be experienced in some of her books— A Motor Flight Through France, French Ways and Their Meaning, Fighting France, and The Custom of the Country, among others. In her honor, a plaque was mounted outside of her rue de Varennes home, part of which reads, “…The first writer of the United States to settle in France out of love of the country and its literature.”

Edith Wharton plaque at 53 rue de Varenne in Paris, photo by Monceau/Flickr

Photo credits: 53 rue de Varenne, where Edith Wharton lived by Monceau/Flickr; Edith Wharton plaque at 53 rue de Varenne by Monceau/ Flickr

Lead photo credit : Photographic portrait of Edith Wharton/ Unknown - Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University/ Public Domain

More in American expats in Paris, famous writers in Paris

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY