Picasso’s Weeping Woman as Artist Instead of Muse: Dora Maar’s Retrospective at Centre Pompidou

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Out of the shadows and into the limelight, Picasso’s primary model for the Weeping Woman, series, Dora Maar, finally gets her due as an artist in her own right, the star of her first solo retrospective exhibition at Centre Georges Pompidou, closing July 29, 2019. Imagine Dora’s delight had she lived to receive such accolades in the heart of her hometown, Paris, where she was born 122 years ago.

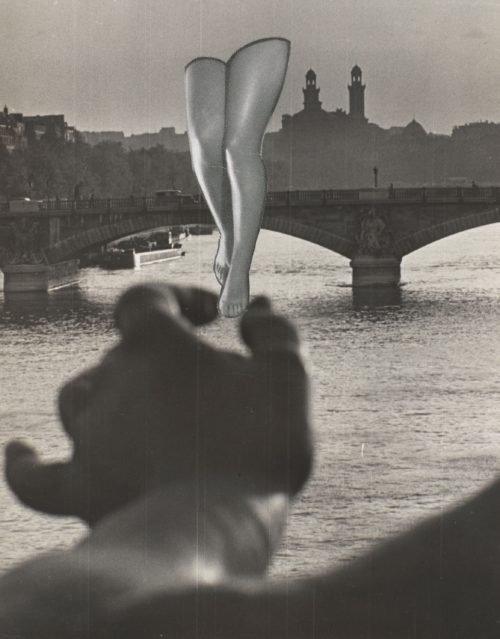

Dora Maar, Model Star, 1936 Silver Gelatin Print, Thérond Collection © Adagp, Paris, 2019, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / A. Laurans / Dist. RMN-GP

Composed of over 400 works in clusters of various media that generously display her artistic talents, this introduction to Dora Maar’s life and art presents a portrait of the modern early 20th-century female eager to make her mark professionally yet torn between her desire for success and a genuine, committed relationship. Often, she will fail at one or the other. For Dora Maar, the decisive moment for her career arrived when she allowed the Spanish master Pablo Picasso into her life. His attentions also brought his condescending opinion of photography, the art form in which she excelled. In this respect, the exhibition Dora Maar not only offers an opportunity to fully explore a relatively unknown body of work, but also asks an enduringly vital question for all aspiring artists, regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation: can the influence of a romantic partner in the arts destroy one’s established or promising artistic career? In this particular case, your opinion of the work will determine your answer.

Dora Maar, Self-Portrait with Electric Fan, Paris, early 1930 Silver gelatin negative on a flexible support in cellulose nitrate, 11 x 6.5 cm. © Adagp, Paris 2019, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP

Born Henriette Théodore Markovitch (also spelled Marković), she became Dora Maar around 1926, when she studied at the City of Paris School of Photography at the age of 19. She was born in Paris on November 2, 1907 to a Croatian architect, Joseph Markovitch (Josip Marković, 1874-1969) and a French woman from Tours, Julie Voisin (1877-1942). In 1910, the family moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where her father received commissions, including one from Emperor Franz Josef I for the Austro-Hungarian Embassy. As we see in the family photographs displayed in albums, Dora Maar enjoyed a financially comfortable existence. She spoke French and Spanish fluently, which served her well during her romance with Picasso. She also spoke and read English. When the family returned to Paris in 1926, she attended the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs and the École de Photographie. She also studied at the Académie Juilien and André Lhote’s atelier, where she met the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson.

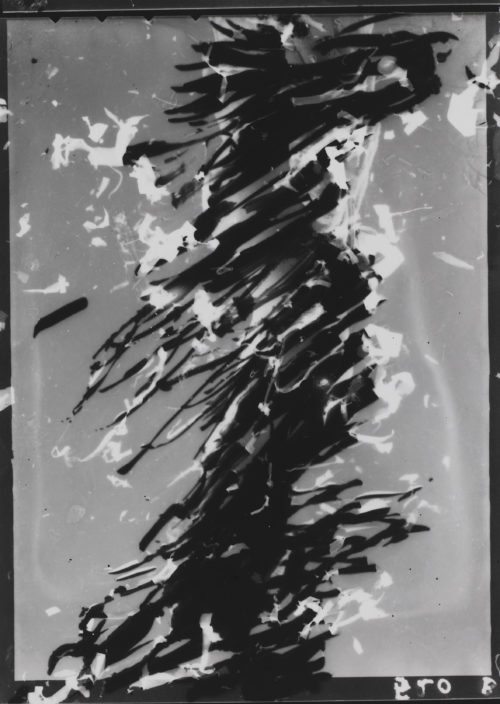

Dora Maar, Untitled, 1935 Silver Gelatin Print, 23.2 x 15 cm Purchased by Yves Rocher, 2011. Formerly in the Christian Bouqueret Collection Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle, © Adagp, Paris 2019 Photo credit © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Dora Maar considered the French commercial photographer Emmanuel Sougez (1889-1972) her mentor. Her first commission was a book on Mont-Saint-Michel written by art critic Germain Bazin. She collaborated with the stage-set designer Pierre Kéfer in 1931. From that experience they formed a business partnership, set up at first in his parents’ garden in Neuilly and then moving to their own studio at 9 rue Campagne-Première, lent by the Polish photographer Harry Ossip Meerson (1910-1991), younger brother of the cinema art director Lazare Meerson (1900-1938), who had worked with Kéber at Film Albatros studio in the mid-1920s. Harry Meerson also lent out his darkroom to the Hungarian photographer Brassai (Gyula Halász, 1899-1984), who became Dora Maar’s close friend. Her contact with Brassai brought her into the Surrealist circle.

Dora Maar, Fashion photograph, Untitled: Seated Model in Profile in Evening Gown and Jacket, ca. 1932 – 1935 Silver Gelatin Print enhanced with color, 29.9 x 23.8 cm Purchased in 1995 Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle © Adagp, Paris 2019, Photo © Centre Pompidou

The Kéfer-Dora Maar studio produced glamorous, innovative images for advertising and portraits, becoming part of the booming industry of commercial photography in glossy magazines. It was a fertile context for Dora Maar’s imagination. Her perspective on the modern women of the 1930s produced models oozing with elegant sensuality. Cool, natural, sometimes athletic, sometimes aristocratic, the Kéfer-Dora Maar female gave off a whiff of eroticize insouciance that emanated from Dora’s own disposition. This conceptualization of contemporary beauty fed the appetite for luxury and leisure time activities, despite the Great Depression. It was a fantasy for some, a reality for others. During this period of working intensely with Pierre Kéfer, Dora had affairs with the filmmaker Louis Chavance (c. 1932-33) and the erotically transgressive writer Georges Bataille (late 1933-1934). The Kéfer-Dora Maar studio closed in 1934.

In 1934, Maar travelled alone to Barcelona and London, shooting photos of ordinary people as she wandered through the poorer parts of these cities. Most of her images featured the downtrodden. By 1932, she had joined the Surrealist social circles. These photo-journalist images reflect the Leftist political activism Dora Maar cultivated on her own and shared with her Surrealist friends.

Dora Maar, 29 rue d’Astorg, ca. 1936 Silver Gelatin Print with Enhanced Coloring, 29.4 x 24.4 cm Purchased in 1990 Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle © Adagp, Paris 2019, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Upon returning to Paris, Dora’s father helped her open her own photography studio at 29 rue d’Astorg. As a proprietor, she remained Henriette Théodore Markovitch on her utility bills, to her neighbors, and in contracts. Her friendships with the Surrealist group intensified, especially with Paul Édouard’s wife Nusch Éluard, who died suddenly from a brain aneurism on November 28, 1946, shortly after a phone call with Dora.

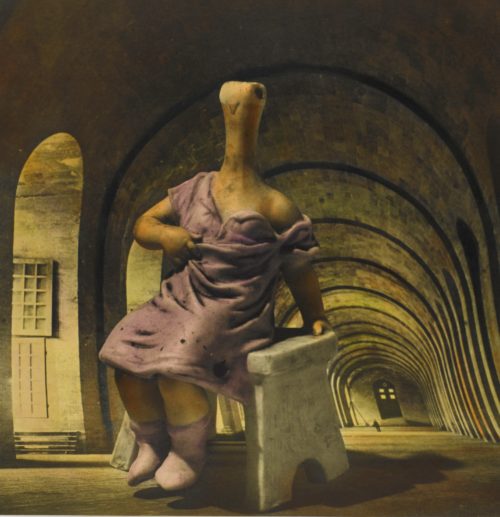

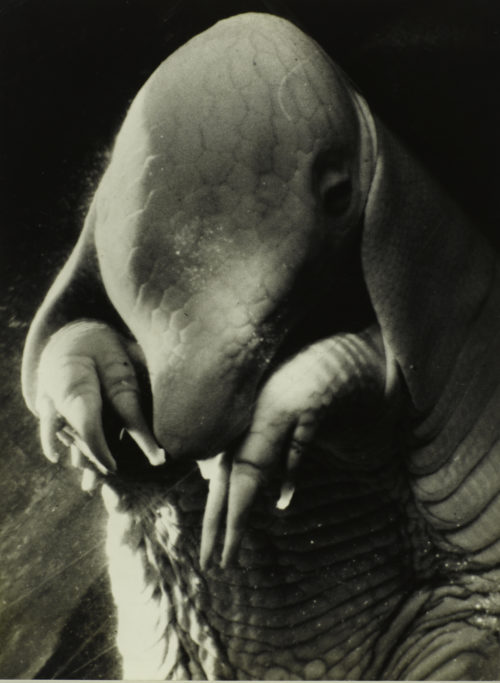

Dora Maar, Portrait of Ubu, 1936 Silver Gelatin Print, 24 x 18 cm Purchase in a public sale in 1998 Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne

Centre de création industrielle © Adagp, Paris, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Dora Maar also participated in the Surrealists’ group exhibitions, such as the one at Charles Ratton’s Gallery in 1936, wherein her Portrait of Ubu became the “icon of Surrealism,” according to her biographer Mary Ann Caws in her exceptional book Picasso’s Weeping Woman: The Life and Art of Dora Maar (2000). “She captures the mysterious,” Caws wrote, “in a combination of the unresolved and the sharply angled. This frequently creates a sense of ambiguity, even menace.” (p. 20) Caws notes that Dora Maar responded to Louis Aragon’s invocation “for each person there is one image to find that will disturb the whole universe.” Maar’s images managed to “disturb and reveal” with a bit of the macabre mixed in. (p. 71)

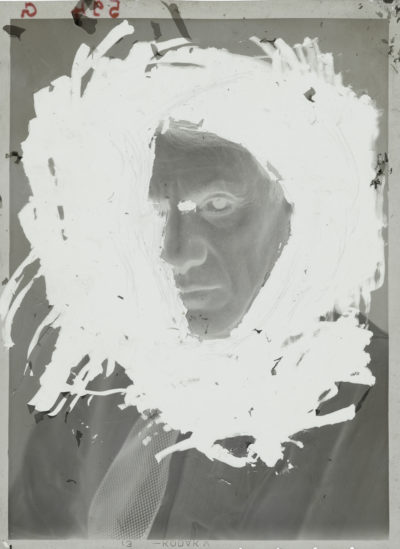

Pablo Picasso, Profile portrait of Dora Maar, sixth state, 1936-1937 Silver Gelatin Print, 30 x 24 cm Musée national Picasso, Paris

And it was through her Surrealist friends that Dora Maar first met Pablo Picasso on the set of the film Le Crime de Monsieur Lange late in 1935, when she was 28 years old. Paul Éluard provided the introductions. The Spanish artist had just turned 54. However, their romance did not take off until their second encounter in early 1936 at the Café des Deux Magots, where Picasso admired Maar’s mad game of stabbing the table with a penknife moving quickly between her splayed fingers. Hypnotically and rhythmically engaged, the younger artist demonstrated her fierce self-assurance and indifference to pain (at least it seemed so then and there). He asked for one of her black gloves embroidered with red roses and stained with her blood. He was smitten. Her intelligent dark beauty (diametrically opposite to that of his current very blond and naïve mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter) stimulated his sexual desire and his need to conquer a challenge. Dora Maar offered him something new and untested in his experience with women: sex with a fellow accomplished artist who also spoke his mother tongue. In fact, Maar was the only Picasso mistress with whom he conversed in Spanish.

Dora Maar, Portrait of Picasso, Paris, studio 29, rue d’Astorg, Winter, 1935-35 Silver Gelatin Negative on flexible support in cellulose nitrate, 12 x 9 cm Purchased in 2004 Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle © Adagp, Paris 2019 Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP

Their affair lasted from 1936 through 1945. During that period, Dora Maar’s photographs of Picasso’s Guernica documented Picasso’s progress as he completed this major masterpiece for the Spanish Pavilion in that year’s World’s Fair, which opened in June 1937. Sources say Dora’s Surrealist photography influenced this commission. The painting responds to the ruthless Nazi bombings of the marketplace at noon in the Basque town Guernica on April 26, 1937. Dora also painted a few grey strokes on the horse.

Dora Maar, Still Life with Jar and Cup, 1945 Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 50 cm Private Collection © Adagp, Paris, 2019, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Unfortunately, Dora Maar began to lose that initial independence in her work. She dropped her artistic photography and returned to painting, not because Picasso forced her to do so, but because she felt his disdain for those who pursued photography as their art form. He believed in the human touch, rather than the mechanical. Her need for Picasso’s approval influenced her decision to consider photography her business career and painting her true artistic vocation. She returned to the brush and palette in order to feel closer to Picasso.

Brassaï, Dora Maar in her studio on rue de Savoie, 1943 Silver Gelatin Print, 30 x 23 cm Musée national Picasso © Adagp, Paris 2019, © Estate Brassaï – RMN-Grand Palais

Seven years after the Picasso-Dora Maar affair began, the 61-year-old Picasso met the 21-year-old artist Françoise Gilot. This relationship bloomed as the one with Dora faded to nothing. In 1946, Picasso and Françoise visited Dora Maar’s studio together. Françoise Gilot reported in her memoir Life with Picasso that on this occasion, the Spanish artist forced Dora Maar into declaring out loud to Gilot that her relationship with Picasso was completely over. This cruel set up was not the last public humiliation Picasso squeezed out of Dora Maar. Within this strained period of 1943 through 1946, Maar focused on her painting by preparing for two solo exhibitions for René Drouin Gallery in 1945 and Pierre Loeb in 1946. Picasso and Dora Maar were still seen at the Café des Deux Magots together and the Spanish artist bestowed little gifts that Maar kept in her personal collection for the rest of her life.

Dora Maar, Untitled, ca. 1980 Silver Gelatin Print, 9 x 6 cm Purchased in 2018 Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle © Adagp, Paris, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

In 1945, Picasso bought a house for Dora Maar located in Ménerbes. She divided her time between this house in the south of France and her apartment on the rue Savoie in Paris. Shortly after the definitive end of her Picasso affair, Dora Maar suffered from a nervous breakdown which was treated with electro-shock therapy in the hospital and sessions with the famous psychiatrist Jacques Lacan, recommended by Paul Éluard. Through therapy with Lacon, Dora sought spiritual comfort. She tried out various religions and settled on her family’s Catholicism for the remaining decades. Her politics also shifted from extreme Left to extreme Right. She died at 89 on July 16, 1987, and was buried in Bois-Tardieu cemetery in Clamart.

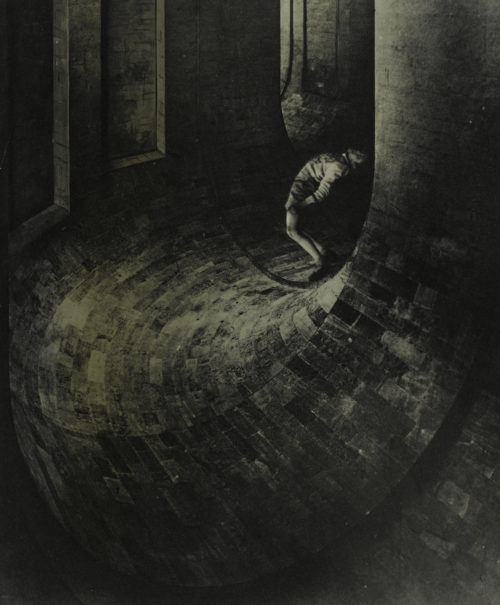

Dora Maar, The Simulator, 1936 Silver Gelatin Print printed on a carton, 27 x 22.2 cm (excluding the margin) Gift from Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach in 1973 Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris Musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industrielle © Adagp, Paris 2019, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

In a recent interview, Brigitte Benkemoun, the author of Je Suis le Carnet de Dora Maar published in May 2019, astutely remarked: “In my eyes she’s a brilliant, charismatic, unpredictable woman, who spent her life in a search for herself that fluctuated between her tremendous arrogance and her doubts. She experienced various periods in her life in an extreme manner, good ones as well as very painful ones, with extremely low points. She was very talented and creative, very passionate, and also totally masochistic. One could say that throughout her life she wanted to be an artist rather than a muse.”

Dora Maar, Landscape in Lubéron, 1950s Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm Private collection of Nancy B. Negley © Adagp, Paris 2019, Photo © Brice Toul

Benkemoun’s book is based on an extraordinary happenstance. She acquired a used Hermès notebook through eBay that would replace her own, no longer manufactured model. Once she received the notebook, she looked inside and found numerous addresses of well-known Surrealists. Her curiosity piqued, this France 2 journalist launched a full investigation and discovered that the original owner of this notebook was Dora Maar. Benkemoun interviewed numerous people based on this cache of the addresses, which led to the descendants and other contemporary connections. The effort yielded more than the usual Picasso Weeping Woman lore she knew before. For one, she learned that Maar was anti-Semitic, gleaned from her encounter with art dealer Marcel Fleiss, the manager of the Galerie 1900-2000, known for exhibiting Surrealist artists. “I won’t sell to you if you tell me you’re Jewish,” Fleiss recalled Maar threatened as they were about to close the deal. Fleiss said nothing and the transaction went through. He lied by omission. This bit of evidence belies Laura Felleman Fattah’s article “Dora Maar: Contextualizing Picasso’s Muse,” published in Woman in Judaism, a scholarly online journal, in which the author claims Dora Maar was Jewish. As mentioned above, Dora Maar became a devout Catholic as part of her therapy with Jacques Lacan, after her breakup with Picasso. Her rationale: “First Picasso, then God.”

Dora Maar, Publicity Study, Pétrole Hahn, 1934-1935 Silver Gelatin Print on a flexible support in cellulose nitrate, 17.6 x 24 cm Purchased in 2004 Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle © Adagp, Paris 2019, Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP

Although the late works are not as significant contributions to the history of art as her Surrealist photomontages, they inform our knowledge of this Parisian artist’s accomplishments in general and beg the question: Was Dora Maar’s brilliant career cut short by the typical conflicts facing professional women in the 1930s, and even today? Or was she a victim of Picasso’s psychological abuse, which chipped away at her original confidence? Was she compromised to the point that she only wanted to please the man she loved? According to art historian John Richardson, Dora Maar sacrificed her gifts on the altar of her art god, her idol, Picasso. Based on the early Surrealist photographs we see in her retrospective, one can only wish she hadn’t taken up with Picasso, for it seems she might have achieved far more in her lifetime without him.

Dora Maar was curated by Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, Curator of Photography and Damarice Amao, Assistant Curator of Photography, for the Centre Georges Pompidou, with the assistance of Amanda Lomax. Their exhibition catalogue in French and English is available online, as well as a tour of the exhibition. Dora Maar travels to the Tate Modern in London this fall. It will be on view from November 19, 2019 through March 15, 2020. Then it travels to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, on view from April 21, 2020 through July 26, 2020.

Lead photo credit : Rogi André (Rozsa Klein), Dora Maar, vers 1937 Silver Gelatin Print, 29.9 x 39.4 cm Purchased in 1983, Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris Musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industrielle © DR Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Georges Meguerditchian / Dist. RMN-GP

More in centre pompidou

REPLY