Paris Photographers: Brassaï, The Transylvanian Eye

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

© Photographie Brassaï/ RMN

Brassaï, born Gyula Halász in 1899, was a Hungarian–French sculptor, writer, filmmaker and photographer who rose to international fame in France during the 20th century. He was born to an Armenian mother and Hungarian father in the ancient village of Brașov, a city in the Transylvania region of Romania, ringed by the Carpathian Mountains. When he was three, his family moved to Paris for a year while his father, a professor of French literature, taught at the Sorbonne. Although Halász was very young, the year in Paris left him with vivid memories of Buffalo Bill’s Circus and the Indian Parade from which his considerable curiosity in the visually unusual grew.

As a young man, Halász studied painting and sculpture at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest and the Berlin-Charlottenburg Academy of Fine Arts. In 1924 he moved to Paris where he spent the rest of his life, joining a handful of other Hungarian emigrants including Robert Capa, among the greatest combat and adventure photographers in history, and André Kertész, the father of photojournalism, who later became Halász’s mentor.

Self-portrait, Brassaï photographing at night. © Photographie Brassaï/ RMN

Halász worked as a journalist, writing for Hungarian newspapers and magazines while living among a remarkable enclave of artists on the left bank of Paris in Montparnasse. American writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Henry Miller rubbed shoulders with exiles who fled their country’s dictatorships, including the Lithuanian (Soutine), the Italian (Modigliani), and the Russian (Chagall). To learn the French language, Halász began teaching himself by reading the works of Marcel Proust, the poetry of André Breton, Louis Aragon, and Paul Eluard. He attended gallery shows of the painters Max Ernst, Joan Miró and Salvador Dali, sculpture exhibitions of Arp, and screenings of films by Luis Buñuel, René Clair and Jean Cocteau. All of these men proved to be influential to his evolving oeuvre.

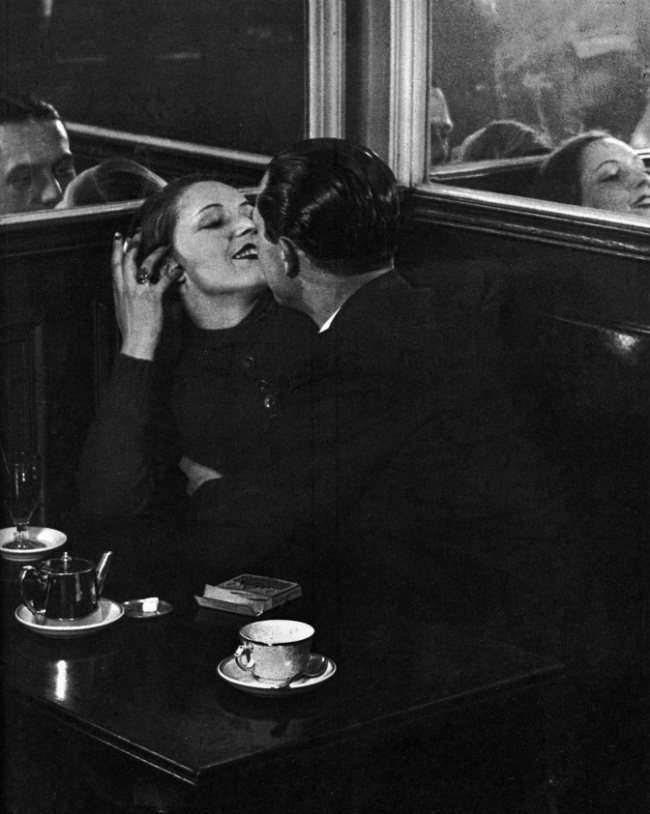

Although he had met a few photographers, including Eugène Atget, he took little interest in the craft, at first considering it to be an inferior form of artistic expression. It was the work, and mentorship, of André Kertész which showed him it was possible to record his visions while wandering Parisian streets at night. Halász preferred Paris between sunset and sunrise because he felt the dark liberated the desires that during the day were overshadowed by reason. He walked for hours around the city in the late evening, sometimes alone, sometimes with a companion. Among those who often went with him were the poet, Jacques Prévert and the writer, Henry Miller, who considered Montparnasse “the navel of the world”.

© Photographie Brassaï/ RMN

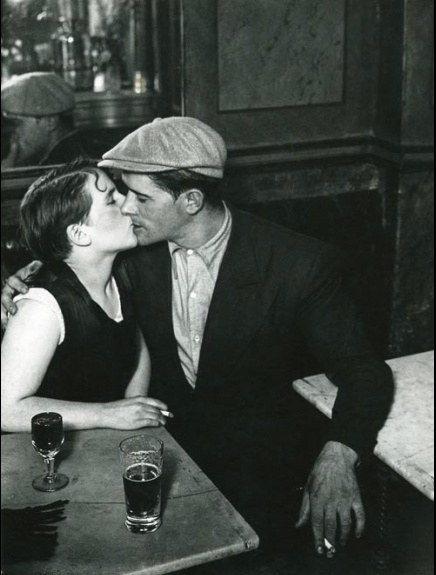

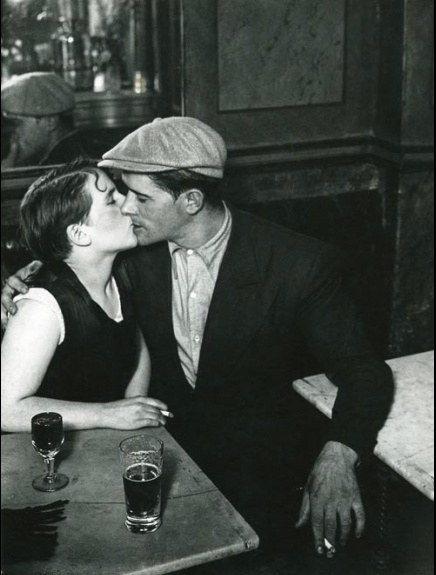

In 1930 Halász picked up his first Voightlander camera. Initially, he worked simply with available light, using long exposures on a tripod, and eventually the newly-introduced flash bulb. He knocked on doors asking to be allowed in to take pictures which revealed the more seedy characters of bohemian Parisian life, including sewer workers, police, prostitutes, gangsters, pimps, backstage scenes in night clubs and brothels, and brazen shows of Sapphic love. Even though it may now have lost its ability to shock, in the 1930s lesbianism was taboo. Halász was working only 30 years after the death of Queen Victoria, who had famously refused to consider legislation banning homosexual acts between women because she was unable to conceive of their possibility.

Pointing his camera through upper windows, Halász focused on conditions of mist or light rain creating strong moods and a tangible atmosphere. He also used mirrors to give different viewpoints of the main subjects of his photos. Although this was a relatively common practice in painting during the previous two centuries, he pursued it in his photographs more than any others had before. It is exactly in this area that his work is at its most documentary, even though many of his shots were deliberately posed. Upon reflection, many years later he wrote, “C’est pour saisir la beauté des rues, des jardins, dans la pluie et le brouillard, c’est pour saisir la nuit de Paris que je suis devenu photographe.“ “It is to know the beauty of the streets, the gardens, in rain and fog, it is to know the Paris night that I became a photographer.”

© Photographie Brassaï/ RMN

Halász captured the enigmatic essence of the Parisian demimonde, publishing his first collection of photographs in a 1933 book entitled Paris de Nuit, Paris by Night, under the single name, “Brassaï”, meaning one who comes from Brașov. The book shocked and captivated the public, becoming a tremendous success, resulting in his being called “the Eye of Paris” in an essay written by his friend Henry Miller in reference to Brassaï’s insatiable curiosity. Brassai also portrayed scenes from the life of the city’s high society, its intellectuals, its ballet, and its grand operas, and he photographed many of his artist friends, including Dalí, Matisse, Giacometti, Braque, Miró, Dubuffet, and Picasso. The latter proved proved to be instrumental in his burgeoning career. Brassaï kept a record of his meetings with Picasso, jotting down the details on scraps of paper, and later, together with the photographs he took during these meetings, forming the basis of his book My Conversations with Picasso, published in 1964.

In 1935 Brassaï bought a Rolleiflex, a twin-lens reflex camera producing 12 negatives on each roll of film, and, perhaps more importantly, offering flash synchronisation. With this camera, he took his first pictures for Harper’s Bazaar, featuring portraits of famous celebrities such as the architect Le Corbusier and writer Samuel Beckett, a close neighbor at his home in the 14th arrondissement. Brassaï worked for the Surrealist publication, Minotaure until 1938. He refused to formally join the Surrealist movement, when invited, on the grounds that he was a realist: “I was only trying to express reality, for nothing is more unreal.”

© Photographie Brassaï/ RMN

With the outbreak of World War II and the invasion of Paris, Brassaï refused to leave his beloved city despite offers of work in New York and elsewhere. Since he would not apply for a photographer’s permit from the occupying Germans, he was forbidden to take pictures in public, although he did begin a record of Picasso’s sculptures in the artist’s studio, which took him until 1946 to complete. Through the war he worked on his drawing and writing, completing Bistro-Tabac, which looked at the problems of the occupation. When the Germans left Paris in 1944, Brassaï formally picked up his camera to record the liberation.

The following year he had his first exhibition of drawings, and also designed a number of stage sets for Jean Cocteau, Jacques Prévert and others, based on his photographs. Prévert was also the screenwriter for the film, Les Portes de la Nuit (1946) directed by Marcel Carné. It captured the feel of the meaner Paris post-war streets following a doomed romance through the world of former partisans and collaborators, which came out in 1946 (issued in the USA as The Gates of Night).

© Photographie Brassaï/ RMN

1948 was a heady year for Brassaï. He became a French citizen, married Gilberte-Mercédès Boyer from the southwestern village of Tarbes, and had a one-man show in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, securing his international fame. In 1951, together with Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Ronis and Izis, he participated again in another Museum of Modern Art show, Five French Photographers. In the 1960s he published a book called Graffiti, of which he wrote, “…With the language of the wall we are not only dealing with an important social fact, but also with one of the strongest and most authentic expressions of art.” He created on tapestries relating to these pictures before devoting himself entirely to sculpture starting from 1968.

Brassaï’s 1933 book, Paris by Night, was reprinted with the photographer’s commentary in 1976. In it he sets out his perspective on the nocturnal underground of the city: “Just as night birds and nocturnal animals bring a forest to life when its daytime fauna fall silent and go to ground, so night in a large city brings out of its den an entire population that lives its life completely under cover of darkness. Some once-familiar figures in the army of night workers have disappeared… The real night people, however, live at night not out of necessity, but because they want to. They belong to the world of pleasure, of love, vice, crime, drugs. A secret, suspicious world, closed to the uninitiated. Go at random into one of those seemingly ordinary bars in Montmartre, or into a dive in the Goutte d’Or neighborhood. Nothing to show they are owned by clans of pimps, that they are often the scenes of bloody reckonings. Conversation ceases. The owner looks you over with a friendly glance. The clientele sizes you up: this intruder, this newcomer – is he an informer, a stool pigeon? Has he come in to blow the gig, to squeal? You may not be served, you may even be asked to leave, especially if you try to take pictures…

And yet, drawn by the beauty of evil, the magic of the lower depths, having taken pictures for my ‘voyage to the end of the night’ from the outside, I wanted to know what went on inside, behind the walls, behind the facades, in the wings: bars, dives, night clubs, one-night hotels, bordellos, opium dens. I was eager to penetrate the other world, this fringe world, the secret, sinister world of mobsters, outcasts, toughs, pimps, whores, addicts, inverts. Rightly or wrongly, I felt at the time that this underground world represented Paris at its least cosmopolitan, at its most alive, its most authentic, that in these colorful faces of its underworld there had been preserved, from age to age, almost without alteration, the folklore of its most remote past.”

© Photographie Brassaï/ RM

Perhaps the photographer most obviously influenced by Brassaï’s work was Diane Arbus. Like him, she set out to look at the underbelly of society. Both carefully set up and posed their subjects facing the camera, thus creating a forceful directness. There is however one nuanced difference between these two great photographers– Brassaï was content to display the mask, while Arbus waited for it to slip.

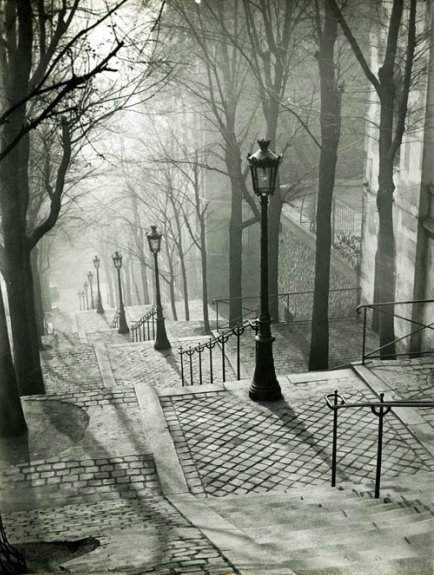

Brassaï died in 1984 and is buried in the cemetery in Montparnasse. His wife donated his remarkable oeuvre to the Pompidou Center.

© Photographie Brassaï/ RMN

Lead photo credit : © Photographie Brassaï/ RMN