Dora Maar Heats Up New York and Paris in Picasso’s Women at Gagosian Madison Avenue and Centre Pompidou

According to the gallery notes for Gagosian’s current Picasso exhibition, the late great art historian Leo Steinberg claimed that the famous Spanish artist (and infamous Lothario) did not paint a woman “as she presents herself to the world, but how she feels inside.”

Dora Maar, Picasso’s mistress from 1935-1942, told her close friend, the writer James Lord: “All his portraits of me are lies. They’re all Picasso’s, not one is Dora Maar.” (James Lord, Picasso and Dora: A Personal Memoir, 1993, p. 123).

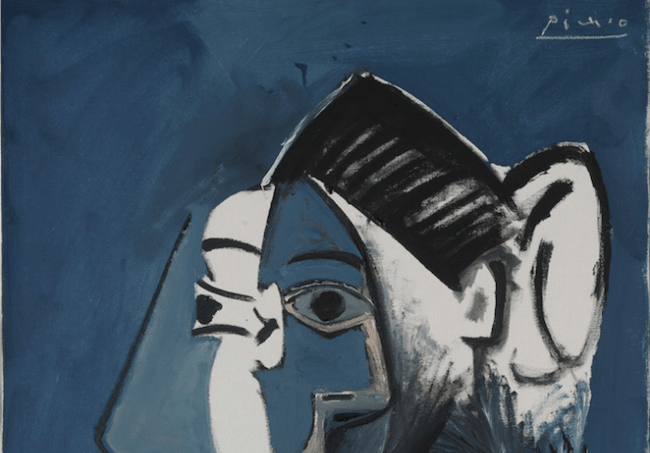

PABLO PICASSO

Buste de femme (Dora Maar), 1940

Oil on canvas

29 1/8 x 23 5/8 in

74 x 60 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Erich Koyama. Courtesy Gagosian.

Whom do you want to believe: the male art historian or the artist’s mistress and model? I choose to believe Dora. The evidence is clear in the current exhibition Picasso’s Women: Fernande to Jacqueline, A Tribute to Sir John Richardson, on view in Gagosian’s 980 Madison Avenue gallery, New York, from May 3- June 29, 2019. Comprised of 36 paintings, drawings and sculptures from mostly private collections, the exhibition came about through a “partnership with members of the Picasso family” to honor the memory of their close friend and colleague, British art historian Sir John Richardson, who passed away on March 12, 2019. Sir John’s magna opus A Life of Picasso, volumes 1-3 (the fourth will be published posthumously), based much of its contents on Picasso’s mistresses’ memoirs and oral accounts, which the gallery notes insist “attests to the central role and influence of many women in Picasso’s life.”

PABLO PICASSO

Le rêve (Marie-Thérèse), 1932

Oil on canvas

51 1/4 x 38 5/8 in

130.2 x 98.1 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library

Courtesy Gagosian.

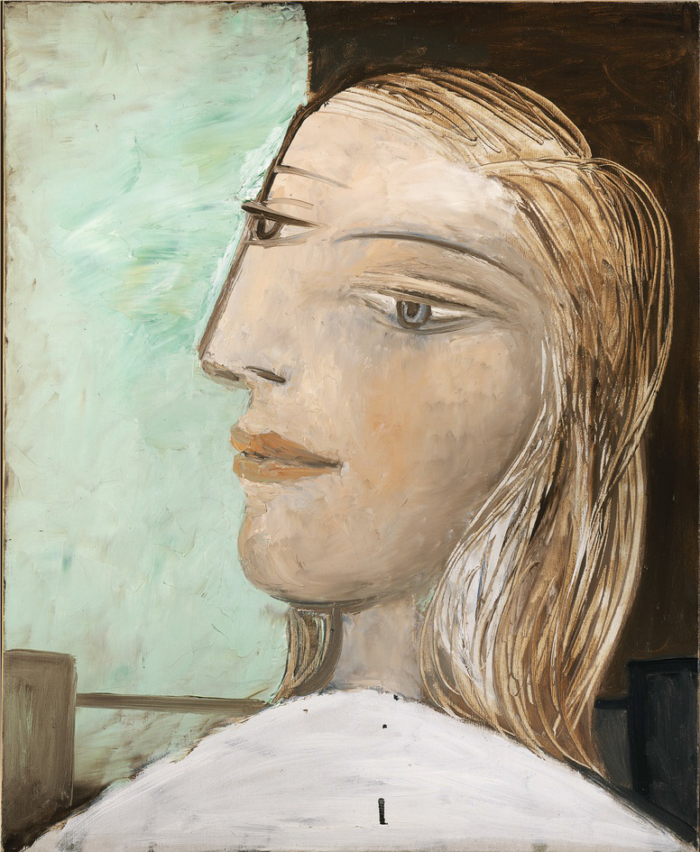

PABLO PICASSO

Portrait de femme profil gauche sur fond vert et brun, 1939

Oil on canvas

28 3/4 x 23 5/8 in

73 x 60 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Maurice Aeschimann

Courtesy Gagosian

Richardson, Gagosian’s main curator for Picasso exhibitions, probably considered creating an exhibition about several Picasso women at one time or another during his long career (Richard died at 95 years old). Of the six shows he organized, two were dedicated to specific relationships: Marie-Thérèse Walther (begun in 1927 and lasting until the artist’s death in 1973; Marie-Thérèse committed suicide on October 20, 1977, five days before Picasso would have been 96) and Françoise Gilot (1943-53).

Over the last decade, Richardson brought together enormous amounts of Picasso artworks, archives, documentaries, photos, and artifacts for Mousqueteros (New York, 2009); Picasso-The Mediterranean Years, 1945-1962 (London, 2010); Picasso and Marie-Thérèse: L’Amour Fou (New York, 2011); Picasso and Françoise Gilot: Paris-Vallauris, 1943-53 (New York, 2012); Picasso and the Camera (New York, 2015); and Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors (London, 2017).

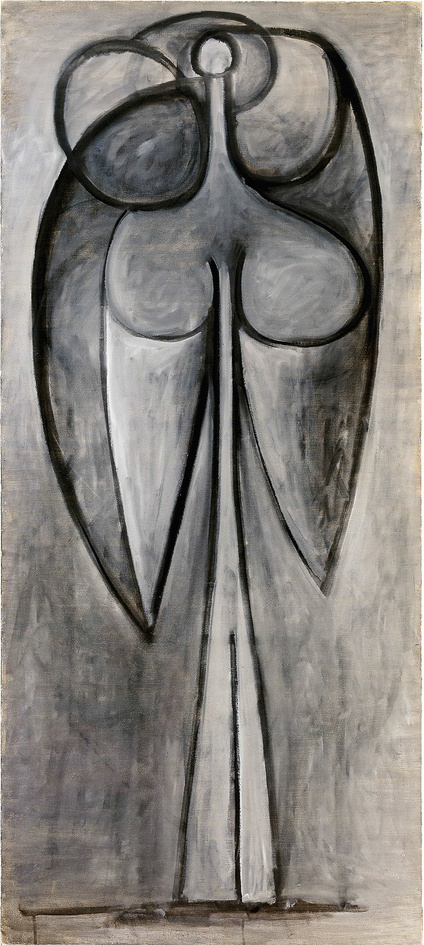

PABLO PICASSO

La femme-fleur (Françoise Gilot), 1946

Oil on canvas

68 1/2 x 26 in

174 x 66 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Gagosian.

PABLO PICASSO

Femme enceinte I, 1950

Bronze

43 x 11 7/8 x 13 3/8 inches

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Gagosian.

However, this one particular Picasso show seems to interrogate the validity of one of Sir John’s main sources, Dora Maar, who is currently the star of her own retrospective at Centre Pompidou in Paris (traveling to London’s Tate Modern and Los Angeles’ Getty Museum this year and the next, respectively) through July 29th. Maar famously observed that once a new woman entered Picasso’s life, everything changed—his art, his home, his literary circle and even his dog. Richardson met Dora Maar through mutual friends living in the south of France, where he shared a home with the collector/curator Douglas Cooper in the Château de Castille. The Richardson-Cooper relationship lasted from 1952 through 1960, when Richardson moved to New York and developed a solid reputation as a Picasso specialist. He worked for Christie’s auction house and Knoedler Gallery, as well as contributed to Vanity Fair, New Yorker, New York Review of Books, and Burlington Magazine well into the twenty-first century. His memoir The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: Picasso, Provence and Cooper was published in 1999.

PABLO PICASSO

Picasso’s Women: Fernande to Jacqueline, 2019, Installation View

Artwork © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

In his memoir Picasso and Dora, James Lord described an evening at Cooper and Richardson’s château where a dinner party of nine included Cooper, Richardson, Picasso, Dora, Lord, the museum curator Jean Leymarie and his wife, Picasso’s son and chauffeur Paulo, and the British ballet critic Richard Buckle. At one point that evening, the group had settled into the living room, where Picasso made a show of taking Dora’s hand to lead her across the length of this immense space toward a secluded spot. “They went slowly, while the rest of us watched in indiscreet silence. And then they reached the corner of the room, where there was a prolonged pause as we waited for Picasso to murmur into Dora’s ear whatever was too intimate, too personal for us to hear, . . . But all of a sudden, having pronounced not a word, Picasso whirled around on his toe and strode back across the salon, leaving Dora alone in the far corner, where she remained a minute in stark solitude before being obliged to return alone across the breadth of the room without the slightest saving grace. It was a painful and odious moment.” (p. 196)

Picasso’s Women: Fernande to Jacqueline

May 3–June 29, 2019

Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, NY.

Lord’s description of Dora’s public humiliation as a malicious tactic on the part of her former lover stuck in my mind since that first reading several years ago, especially in light of the #MeToo movement, which has blocked exhibitions of known sexual offenders, such as Chuck Close. As recently as last year, a critic for Hyperallergic, an online art magazine, questioned the ethics of attending a Picasso show at the Tate Modern. My students discussed this dilemma at length, weighing the nurturing study of his art against their awareness of his maltreatment of women—most famously, Françoise Gilot’s recollection in her memoir Life with Picasso of the threat to brand her with a lit cigarette as he held it close to her face in the midst of a tantrum. The title Picasso’s Women necessarily provokes contemplation of this notorious tombeur’s destructive behavior toward his two wives and many mistresses, bringing to the fore, once again, a moral challenge for feminists ill-disposed toward honoring the offending perpetrators in any way. In this case, does one ignore the acknowledged bad behavior and attend the show for the sheer pleasure of savoring this glorious opportunity to see rarely exhibited Picasso artworks from private collections and two museums, The Nasher Scupture Center in Dallas, Texas and The Fitzwilliam Museum of Cambridge [England]? Or does one boycott the show to honor one’s own moral convictions?

PABLO PICASSO

Tête de femme (Fernande), 1909

Bronze

16 x 10 1/4 x 10 in

40.6 x 26 x 25.4 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Courtesy Gagosian.

I certainly cannot exonerate Picasso. The abundant evidence of psychological and physical abuse qualifies for a #MeToo moment of evaluation and reflection. Furthermore, invoking Leo Steinberg’s belief that Picasso’s captures how a woman “feels inside” smacks of insensitivity, if not pure absurdity. To my way of thinking, Picasso painted what he felt about women in general and that one woman who inspired a particular piece. The complexity of the topic has filled scores of books on the Spanish artist. As of this writing, there is no catalogue available to comment on the Gagosian curator’s/s’ analysis for this specific collection of works in Picasso’s Women. Therefore, we cannot know what new insights or revelations the curator/s might share.

PABLO PICASSO

Picasso’s Women: Fernande to Jacqueline, 2019, Installation View

Artwork © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

My own views on Picasso’s conception of women in his art continue to evolve. In this case, I chose to concentrate on the art making and never assume that this artist offers any insight into the sitter’s true self or soul. We do witness Picasso’s sexually-charged infatuation (perhaps, real love) for the female subjects referenced here. We also witness his profound hatred, specifically in Le Repos [Olga Kokhlova], 1932. Some works speak of his feeling for luscious sensuality, others for enchanting classical beauty, and still others for his extremely cruel mind, fueled by deep-seated hostility (or insecurity), capable of producing monsters as terrifying as Hieronymus Bosch’s creatures in Hell.

PABLO PICASSO

Mère et enfant (Portrait d’Olga), 1922

Oil on canvas

51 1/4 x 38 5/8 in

130.2 x 98.1 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Rob McKeever

Courtesy Gagosian.

Yes, the master’s brush strokes, modeling, composition, color, innovation of form in space, and overall visual inventiveness ceaselessly intrigue and satisfy our careful study. Here, the sheer application of paint astonishes with it lyricism and ease of flow. It should be acknowledged that Picasso responded to all manner of stimuli to nourish his art. Not only women, but also men, masks, toys, environments, and so forth, triggered changes in his stylistic directions. He also developed different inquiries for different stimuli, not just in response to new sexual partners or crushes (Sarah Murphy and Sylvette David), as Dora Maar asserted reductively, but in response to the different body shapes on his radar screen. In the new book Pablo Picasso and André Salmon: The Painter, the Poet and the Portraits, literary scholar Jacqueline Gojard describes the myriad iterations of André Salmon’s figure in sketches around 1907, the year Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Did these drawing exercises catalyze Picasso’s visual vocabulary at the time?

PABLO PICASSO

Portrait de femme a la queue de cheval, Sylvette, 1954

Oil on canvas

39 3/8 x 31 7/8 in

100 x 81 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy Gagosian.

Whether we marvel at the sculptural buildup of white and gray touches in Bust of a Woman with Raised Arms (1922), a portrait of Olga Kokhlova (his first wife from 1917 to her death on February 11, 1955) or the austere angularities accentuating the hip hairdo of a 1950s teenager in Portrait of a Women with a Ponytail, Sylvette [David] (1954), we must admit that this guy Picasso could really paint well! There is joy in spending a long time examining the surface of a Picasso painting, drawing or sculpture. The layered strokes and the quickly brushed passages remind us of Picasso extraordinary control and distinctive visual expression. Picasso did indeed have an intuitive sense of physicality. Most likely, Picasso’s innate apperception of the body came from his relationship to the body of the model and the physicality of his own experience with her body and her mind.

It is the physicality and conceptual intentionality of Picasso’s work that drives away ordinary considerations. His art is superior in so many ways and a welcome relief from today’s Photoshop and virtual reality. Although this well-chosen, well-organized exhibition of Picasso’s work is almost over, the photos illustrating this essay offer a vague sense of an actual gallery visit.

PABLO PICASSO

Picasso’s Women: Fernande to Jacqueline, 2019, Installation View

Artwork © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

Above all, let us not forget that our presence in the galleries honors the memory of Sir John Richardson, whose breadth of knowledge on Picasso and curatorial range will be sorely missed by his loyal fans.

One caveat: Picasso’s Women is not a comprehensive survey of the major women in Picasso’s life. His mother, sister, a few short-lived affairs, Eva Gouel (aka Marcelle Humbert, 1911-15), and the poet Paul Eluard’s wife Nusch are among the many women who influenced Picasso’s life and career, but are not included in this survey. Most of the mistresses and wives are described in Arnie Greenberg’s Glory Days: Picasso, published right here in Bonjour Paris and in my contributions elsewhere.

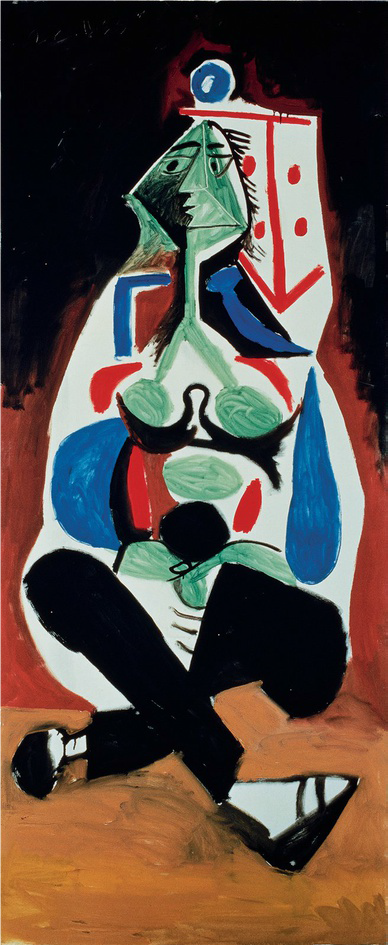

PABLO PICASSO

Femme aux jambes croisées, 1955

Oil on canvas

75 x 31 1/2 in

190.5 x 80 cm

© 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Gagosian.

Missing too are Picasso’s daughters, Paloma Picasso (born April 29, 1949 to Françoise Gilot) and Maya Widmaier-Picasso (September 5, 19354 to Marie-Thérèse Walter), whom Picasso painted as chubby toddlers. Maya commented: “Sometimes, you see that he’s clearly doing a self-portrait through the features of his daughter. It’s not a portrait of a child, you know? She’s meant to be three years old, and there is something very severe about the way she looks… Certainly, he found a feminine projection of himself within his daughter.” (Cody Delistraty, “How Picasso Bled His Women in His Life for Art,” The Paris Review, November 9, 2017)

With Maya’s quote as the final word on the subject, let us consider the possibility that these paintings, drawings and sculptures of women are not about how they present themselves to the world, but how the Spanish master himself feels inside.

PABLO PICASSO

Picasso’s Women: Fernande to Jacqueline, 2019, Installation View

Artwork © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

Lead photo credit : PABLO PICASSO Tête de femme, 1963 Oil on canvas 28 3/4 x 21 5/8 in 73 x 54.9 cm © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Patrick Goetlin. Courtesy Gagosian.