Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin: The Tragedy of Muses

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

To be the muse of a famous artist has proved often to be a double-edged sword. To be talented in your own right and female, that sword could possess the unkindest of blades.

In Beth Gersh-Nesic’s excellent recent article on Dora Maar’s retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, she details Picasso’s often negative, influence on Maar’s own progression as a photographer and an artist. As his mistress and muse, Maar suffered doubly– her work subsumed by Picasso’s reputation and later being replaced in Picasso’s life by the 21 year old Françoise Gilot. Maar subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown.

The Mature Age, 1913 bronze casting in the Claudel room at the Musée Rodin in Paris. (The figure standing behind, ensnared in her own hair, is Clotho, 1893). Image credit: Wikipedia (CC BY 2.0)

Camille Claudel could never have hoped to aspire to the fame of Rodin and her years of being Rodin’s muse and mistress did not end when a younger model came along, but instead by Rodin’s refusal to end his long relationship with Rose Beuret, who was 20 years her senior.

Claudel’s breakdown, unlike that of Maar, was not a transitory phase in her life but a cruel end to the career of a truly talented sculptor. In 1913, everything conspired against Claudel: her gender, her breakdown and her family.

It had all started with such hope.

Camille Claudel was born in 1864 in Fere-en-Tardenois in the Aisne department. Her family were educated and prosperous; her father was a Register of Mortgages for the government, and her mother, the daughter of a doctor and the mayor of Villeneuve-sur-fere. Camille was one of two other siblings, Louise and Paul, but it was Camille who earned the ire of her mother who, if she had found her willful and unruly as a child, was totally and irrevocably opposed to her choice of career as an adult. (Her mother, Louise-Athenaise Cécile Cerveaux, had been left motherless at the age of four and it has been suggested that she lacked a maternal instinct. This was irrefutably true of her relationship with Camille, resentful not only that she was not a boy but that she was strong willed and often difficult.)

Camille had discovered modeling with clay from a very early age and the fascination with the medium had never left her. When Claudel was 12 years old her father was transferred to Nogent-sur-Seine, a mere 60 miles from Paris but more importantly the home of two respected sculptors, Paul Dubois and Alfred Boucher. Camille’s father, who was much more sympathetic to her obsession with sculpture but unsure of her talent, approached Boucher for an opinion of her work. Camille was then 15 years old and Boucher was astounded by her abilities and encouraged her father to not only take her talents seriously but also to help her pursue them.

Women were still not allowed to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but Boucher introduced Camille to Paul Dubois who had been his own professor at the Beaux-Arts. Also recognizing Camille’s talents, he recommended she attend the Académie Colarossi.

The Académie Colarossi had been founded by the Italian sculptor, Filippo Colarossi, and had moved in 1870 to the rue de la Grande-Chaumière in the 6th arrondissement. It was a natural progression for female students unable to study at the Beaux-Arts, and where they were allowed to draw nude, male models.

Claudel’s father, who had once again been transferred to a different location, this time even further from Paris, agreed to rent an apartment on the Boulevard Montparnasse for the family, the children’s education, and, most importantly, to facilitate in Camille’s artistic dreams.

Camille Claudel (left) and sculptor Jessie Lipscomb in their Paris studio in the mid-1880s. Image credit: Wikipedia, public domain

Aged 17 in 1881, Camille entered the Académie Colarossi and immediately made friends with a group of young women sculptors who shared a studio in Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. (Three of the women were English: Jessie Liscombe, Emily Fawcett and Amy Singer. Camille subsequently traveled to England staying in Frome with Amy Singer and Jessie Liscombe in Peterborough. Jessie Liscombe visited her in the asylum 48 years later and protested against her incarceration, insisting she was not insane.)

Alfred Boucher, who had been teaching the sculptors for three years, was offered a prodigious position in Florence and suggested that Rodin take over from him in their instruction.

Camille was already taking her sculpting with a serious intensity before she even met Rodin, and had produced a plaster bust of the goddess Diana and a bronze bust of her brother Paul as well as a starkly naturalistic bust of the family’s housekeeper Hélène, her wrinkles and lines portrayed without sentimentality and entitled, La Vieille Hélène.

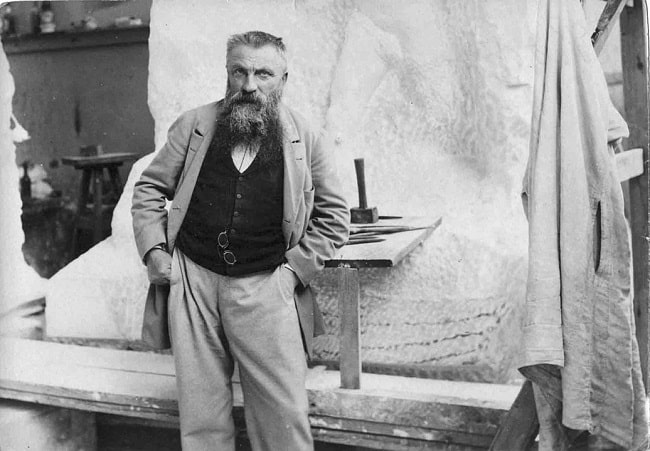

Camille was not yet 19 when she met Rodin who, at 43, was 24 years older.

Rodin was by then a recognized, sought-after sculptor, his many commercial, ornamental figures adorning public and private buildings, especially in Belgium, the proceeds from which had allowed him to travel to Italy where the sculptures there impassioned him enough to return to Paris in 1877 to fulfill his own ambitions, his own grand ideas not influenced by having to please private clients.

His first major sculpture, which later became known as The Age of Bronze, so life-like in its depiction of a young man emerging from depression and misery into enlightenment, was pilloried by fellow artists and critics who accused him of taking the plaster cast directly from a living model. Rodin was appalled at these accusations and fortunately the French government must have agreed and not only paid for the first bronze cast but also for the bronze cast of his sculpture of St John the Baptist preaching in the wilderness. St John the Baptist was a powerful sculpture, emaciated but muscled, beautifully delineated; it was hardly surprising that the French government then commissioned Rodin to make an elaborately patterned bronze door for the Musée des Arts décoratifs. What was even more appealing for Rodin was that the theme was left to him.

It was into this milieu of almost manic creativity that the young Camille Claudel stepped in 1884.

To be a student of Rodin, the larger than life, enigmatic, genius that the artist was certainly perceived to be, must have been heady stuff for an 18 year old, who only wanted to do one thing in her life: sculpt. To learn from the master could not have failed to turn her head, but there is no doubt that their attraction was mutual and took little time to reach fruition.

The attraction of Claudel for Rodin was of course much easier to explain. Her youth, beauty, talent and sexuality were irresistible to the 43 year old, who, already used to having his pick of his young models, and not discounting his 20-year affair with his long-suffering mistress Rose Beuret, still knew almost immediately that the intriguing, Camille Claudel was a different proposition altogether. Rodin was soon passionately in love with her.

Head of Camille Claudel, 1884, by Auguste Rodin, portrays Claudel wearing a Phrygian cap, on exhibit at the Museo Soumaya. Image credit: public domain

It was in the same year that Rodin made his first portrait bust of Claudel, an arresting, austerely beautiful bust. (The bronze cast is now in the Orsay museum.) Rodin was utterly smitten with Claudel; she had swiftly become not only his model and lover but also his muse and confidante.

Camille Claudel may well have become Rodin’s lover but she was no pushover, no compliant little thing, and refused to live with Rodin while he maintained his long term mistress, Rose Beuret, whom he could not, or would not relinquish. In the meantime, knowledge of her affair had reached her family in Montparnasse and her mother’s already implacable, innate disapproval of Camille’s artistic life, boiled over at her daughter’s involvement with Rodin, and Camille was left with no choice but to leave the family home.

As well as working on Rodin’s sculptures, albeit like his other students, on minor details, (Rodin was now working on the monumental, The Burghers of Calais), Claudel was producing and exhibiting her own works. And here of course was the inevitable and often insurmountable Catch 22 of studying under a master. How can your own work not be influenced by your teacher? How will it be accepted as a stand alone piece of art? How will it not be criticized as a poor copy? How will it ever be accepted as original?

For Camille Claudel, fiercely independent, fiercely ambitious, prodigiously talented, she would be dogged by these criticisms for many years. She was however fighting for her own style, bolder, more imaginatively lyrical and often overtly sexual which while acceptable from a male sculptor was considered unseemly from a female artist. (Indeed so entrenched was the disapproval of women artists depicting sexual themes in their work, that even after Claudel and Rodin’s affair had ended, Claudel had to still depend on Rodin for his collaboration, often having to accept that he would get the credit for her sculptures.)

The eight years Claudel spent as Rodin’s mistress and pupil had an incalculable effect on Claudel’s progression in honing her talent but the affair ended badly, possibly with an abortion, probably not the first and the brutal realization that Rodin was never going to give up Rose and the ‘marriage contract’ drafted by Rodin and doubtless dreamed up by Claudel was not worth the paper it was written on. The ‘contract’ drawn up in October 1886 stated amongst other things that Claudel would be Rodin’s only pupil, that he would support her by every means including by the use of his inheritance, promote her work and that in the year that followed, they would be married. Whilst it is irrefutably true that Rodin was not seeking either marriage or to be tied down to one woman, despite being in love, it is also true that Claudel also in love, was nevertheless fearful of being subsumed into a binding relationship. Claudel was mercurial, unpredictable and not afraid to argue with anyone, least of all Rodin. Despite their often tempestuous relationship, both were sculpting figures of lovers with significant allusions to their own situation. Rodin’s Fugit Amor, The Eternal Idol, The Kiss, and Claudel’s magnificent bust of Rodin completed in 1888.

By 1890, the ménage à trois and Claudel’s dissatisfaction of being left behind by Rodin’s now unstoppable fame, led her into a state of apathy and self isolation, avoiding Rodin when she could. The affair staggered on for another two years, but in 1892, Claudel finally moved out of Rodin’s studio. However, Claudel was in no position to leave Rodin completely and Rodin continued to support her both financially and influentially.

The Waltz, conceived in 1889 and cast in 1905. Image credit: Wikipedia, public domain

Free, at least of Rodin’s tutelage, Claudel’s originality began to blossom. The Waltz, completed in 1905, Clotho in 1893 and L‘Âge mûr in 1894 were extremely personal sculptures. In L‘Âge mûr, in plaster, the composition consists of three naked figures; the man in the middle being torn between his young lover and his old mistress who is clearly winning the battle.

The old woman is pitilessly sculpted, ugly, wrinkled and with pendulous breasts; there can be no mistake it alluded to Rose Beuret. In the final version, completed in 1898, the young woman’s hand has slipped out of the man’s grasp completely and he has turned away from her. When Rodin saw the sculpture for the first time in 1899, it so shocked and angered him that he immediately stopped all his support for Claudel. (The 1913 bronze cast of The Age of Maturity can be found in the Claudel Room in the Rodin Museum.)

Claudel continued to sculpt and exhibit her work but she was never credited with the success she deserved. Her life was difficult, sculpting was not cheap and spurning Rodin and his patronage resulted in her giving up her little studio on the Boulevard d’Italie, moving into a two-roomed apartment on the Ile Saint Louis and depending on financial assistance from her patrons.

By 1905, Claudel was starting to display signs of mental illness, and she secluded herself in her workshop. Most of Claudel’s paranoia was aimed at Rodin and her behavior over the next years became more and more extreme. She neglected her appearance, threw impromptu parties on the banks of the Seine and sent begging letters to her family. Rodin, behind the scenes, still attempted to obtain a state commission for her. Claudel’s father secretly sent her money, but on his death in 1913, her mother and brother Paul (now a poet, a diplomat and devout Catholic) took immediate advantage of the situation to remove Claudel effectively from their lives and prevent her from further damaging their respectable reputation.

Immediately after her father’s funeral– to which Claudel had not been invited to, as she had not been even informed of his death– Paul Claudel applied for a medical certificate to intern his sister into an asylum. A week after her father’s death on March 10th, Camille Claudel was physically dragged from her apartment and committed to the Ville-Evrard asylum outside Paris.

Despite a short flurry of press protests criticizing this antiquated law allowing anyone to be committed, with little or no cause, the family remained obdurate, and Camille remained incarcerated.

While there is little doubt that Claudel had mental problems, different doctors at various stages of her incarceration found her clear headed when she worked on her art and tried to persuade the family that she should be released. All such requests were flatly denied. Her mother never visited Claudel once in the 30 years she was locked away. Her brother Paul visited her all of seven times and always referred to Camille in the past tense.

At the start of the Second World War, Camille Claudel and a number of other women were transferred to the Montdevergues asylum, six miles from Avignon. She remained there until her death aged 79 on October 19th, 1943. No family attended her funeral. Claudel was interred in in the cemetery of Montfavet. In 1953, her bones were transferred to a pauper’s communal grave.

Claudel had destroyed a significant amount of her work but her genius lives on, not only in the Camille Claudel room in the Musée Rodin but also in the Musée Camille Claudel in her teenage home town of Nogent-sur-Seine.

As for Rodin? In 1917, in a final piece of irony that Camille would not have appreciated, Rodin married Rose Beuret, his mistress of 53 years. Beuret died two weeks later and Rodin, ten months after Rose. He was 77 years old.

Love Paris as much as we do? Get some more Paris inspiration by following our Instagram page.

Le Musée Camille Claudel. Image credit: Flickr, Jean-Pierre Dalbéra (CC BY 2.0)