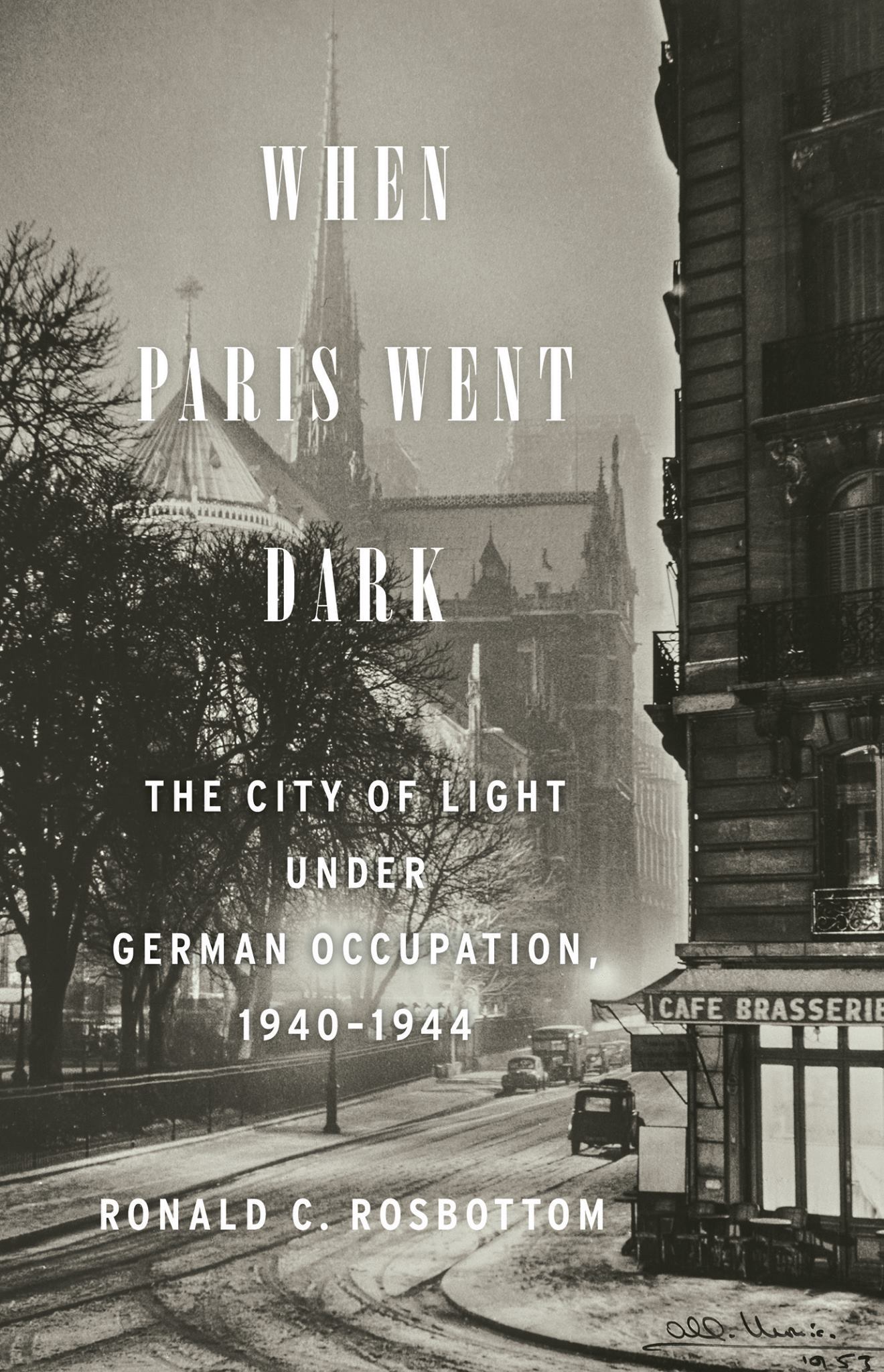

Author Interview with Ronald Rosbottom: When Paris Went Dark

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Present day Amherst, Massachusetts is worlds away from 1940s Paris, France.

In Amherst, Ronald Rosbottom is the Winifred L. Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities and Professor of French and European Studies at Amherst College. He is also the author of When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944, published by Little, Brown and Company.

For this gripping account of Paris under occupation, Rosbottom was a semifinalist for the National Book Award and a finalist for the Best Book on A French Subject offered by the American Library in Paris.

In researching the book, Rosbottom dove into a wide array of resources from the era, like interviews, memoirs, photographs, diaries, and letters. As a result, the book is an excellent, well-researched, and engaging portrayal of Paris during a turbulent time.

I was lucky enough to speak with Professor Rosbottom about his book, his interest in French history, and Paris during its darkest days.

How long have you been interested in the history of Paris? And what sparked that interest?

Probably it was growing up in a half-Cajun family, in New Orleans, that first got me interested in France and French history. And I went to Tulane University as an undergraduate, so it was natural that, when I decided to go junior year abroad, Paris would be my destination. The intense love affair began when I was barely 20 years old. Obtaining a degree in Romance Languages at Princeton, and marrying someone who loved Paris as much as I did, meant that the city became one of our life destinations, and has remained so for almost 50 years.

Your book is about the German Occupation of Paris in the 1940s. How would you describe the book in one sentence, and where did you get the title?

What daily life was like, both for Parisians and for their occupiers, during France’s “dark years.”

The title refers to a song by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein, written and sung all over the world in 1941: “The Last Time I saw Paris.” The last verse refers to the City of Light now being dark.

For someone who knows nothing about this period of Paris’s history, can you offer a brief synopsis of what occurred from 1940-1944 in Paris?

The German Army invaded the Low Countries and France on May 10, 1940. By June 14, Paris had surrendered, as an open city. That meant that it was not bombarded, nor was it defended.

The defeat of France took about six weeks, and was ended when the French Government dissolved the Third Republic, and established a new État français, with World War I hero, Philippe Pétain, as its leader, and set up its capital in Vichy.

France was divided into two parts: Occupied and “Free Zone.” Paris was in the former, and was where the Wehrmacht for France had its headquarters. The Parisians were under the control of the army (the Wehrmacht), the German civil authority (the Gestapo, the Foreign Service, and the Propaganda Ministry), and partly the “Vichyistes,” the French collaborators. These entities were often in competition with each other.

Have other books like yours been written, and if so, how is yours different?

Books about the daily life during the Occupation have been written, primarily in French, but none for a general American audience. Though my book was simultaneously published in Great Britain (and has just appeared in a Dutch edition), I wrote it for an American readership, for I had found how little we knew about military occupations in general, and that one in particular.

How much research did this book entail, and how and where did you conduct it?

The research was extensive, primarily because I didn’t know as much as I thought I did about the period. I trained as a literary historian of 18th- and 19th- century Europe. Consequently, in order to move into the 20th century, I had to read histories, original archives, letters, memoirs, and entice persons into telling me of their own memories. It took much longer than I thought it would.

I conducted my research primarily in Amherst, where I teach at Amherst College, in Washington, D.C., in New York City, in London, and in Paris.

What were the most disruptive effects of the Occupation on Parisians of that epoch?

Nothing, absolutely nothing, remained “normal,” so much so that the memories of that period still inflect Parisian life today. Food, clothing, transportation, families, fuel, pets, neighborliness, trust, entertainment, even religious ceremony were all somehow touched by the presence of an increasingly violent and nervous occupation.

Apart from the very obvious ways that Paris changed during the Occupation, did the city change architecturally in important ways?

Architecturally, not much, though there remain in Paris today large German bunkers, one I’ve visited at the Gare de l’Est, that are too large to blow up. But Paris was barely bombed during the war, and that was what made the Occupation so uncanny. The city looked the same, but it wasn’t. Different traffic patterns, absence of automobiles, fewer métro trains, thousands of bicycles meant that the architectural environment had to be negotiated much more carefully. Culturally, much changed, for all forms of entertainment were censored, museums were closed, newspapers were controlled, newsreels were German-produced, even the cinema, the primary outlet for Parisians, was overseen by the German Propaganda Ministry.

Paris and “la bonne chère” are synonymous. How did the city’s love affair with eating and nourishment change during this period?

In terms of food, folks weren’t talking about the newest restaurants, the coolest chefs, or the most innovative cuisines. The well-connected collaborators and the upper echelon of German bureaucrats did indeed dine at Le Tour d’Argent and Maxim’s. But for the most part, raising rabbits in one’s attic, learning to love potatoes and Jerusalem artichokes, and begging friends and relatives in the countryside to provide some nourishment were the activities that preoccupied mothers and wives. No foodstuff could be bought without food stamps, and without standing in interminable lines. Many children had serious vitamin deficiencies, but no one starved.

Do you think there have been any holdover effects, or are there lingering outlooks held by Parisians as a result of that decades-old occupation?

Yes, and it recently manifested itself with the “Charlie Hebdo” and kosher supermarket attacks. Memories of past anti-Semitism, and of a foreign presence imposing its will through arms came immediately to the fore. France still struggles with the history of its World War II complicity in the surveillance, arrest, and deportation of Jews, French and foreign, so such acts revive uncomfortable reflections.

On a lighter note, what are some of your favorite things to do in Paris? And what do you love most about French culture?

The French still, thank goodness, believe in a joie de vivre. Living is as important as working. We all know how seriously they take their leisure time; no country takes more “vacations.” This is all changing, as global consumer capitalism worms its way into their culture, but taking time to live is still one of the most admirable traits of French life.

I like nothing better than walking Parisian streets, especially in quartiers I do not know well, and sitting in a Parisian café. In this way, I can see for myself what joie de vivre is.

Who are some of your favorite authors?

For fiction: Toni Morrison, Ian McEwen, W. S. Sebald, Gustave Flaubert, Patrick Modiano. For non-fiction: Diane Ackerman, Tony Judt, Elaine Showalter, Stacy Schiff, Joseph Ellis, and James Wood.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers?

For writers of fiction and poetry, trust your imagination, and trust your readers. You don’t have to fill in all the blanks; your most astute readers will do that—want to do that–which will make your work compelling, and returnable-to.

For writers of non-fiction, tell an arresting story. Don’t let facts dull your narrative.

Lead photo credit : Archived photo excerpt from "When Paris Went Dark"/ Ronald Rosbottom/Facebook

More in books on WWII, Paris books, WWII in Paris